API-First Design: The Consumer-Last Trap

How API-first principles backfire when developers forget who actually uses their interfaces

API-first design promised to revolutionize how we build software. Design the interface first, the theory goes, and everything else falls into place. But somewhere between the OpenAPI specs and the RESTful principles, we’ve created a generation of APIs that are technically perfect and practically unusable.

The Beautiful Theory of API-First

The API-first movement emerged as the antidote to decades of haphazard API development. Instead of treating APIs as afterthoughts, the leftover plumbing exposed after building the “real” application, teams would design the interface first. This approach promised consistency, scalability, and developer happiness.

The best practices are well-documented: REST fundamentals, proper error handling, versioning strategies, rate limiting, pagination, idempotency, filtering, and sorting. On paper, it’s flawless. In practice, it’s where the trouble begins.

When Best Practices Become Worst Experiences

The problem isn’t the principles themselves, it’s how they get implemented. Teams become so focused on checking the “API-first” boxes that they forget the fundamental question: Who is actually going to use this thing?

Consider pagination. The technical debate between offset versus cursor pagination is well-trodden territory. Offset pagination allows random access but suffers performance issues at scale. Cursor pagination is efficient but doesn’t support jumping to specific pages.

The API-first team chooses cursor pagination because it’s “more scalable.” They implement it perfectly according to the spec. But then the frontend team discovers they can’t build a page-number navigation system. The mobile team finds they can’t implement “jump to last page” functionality. The data analytics team can’t sample random records.

Everyone followed the best practice, except the practice wasn’t best for the actual consumers.

The Versioning Vortex

API versioning represents another classic case of theory versus reality. The textbooks recommend putting versions in the URL path: /v1/users, /v2/users. It’s clear, predictable, and follows REST principles. But then you deploy to production.

Suddenly you’re maintaining multiple active versions. Your monitoring dashboards become cluttered with /v1/*, /v2/*, /v3/* endpoints. Your documentation grows exponentially. Your client teams can’t agree on when to upgrade. The clean theoretical model becomes a operational nightmare.

The alternative, using headers or query parameters, isn’t any better. Headers are invisible and hard to debug. Query parameters violate the REST principle that URLs should represent resources, not actions.

Error Handling: Technically Correct, Practically Useless

HTTP status codes represent perhaps the most abused aspect of API design. The API team returns a pristine 400 Bad Request with a perfectly formatted JSON error body. They’ve followed all the best practices.

But the mobile developer receiving this error has no idea what to do with it. Was it a validation error? A missing parameter? A type mismatch? The status code says “bad request” but doesn’t say what was bad about it.

The frontend team can’t show meaningful error messages without parsing the response body and implementing complex error handling logic. The status code becomes essentially meaningless, every error requires the same generic handling.

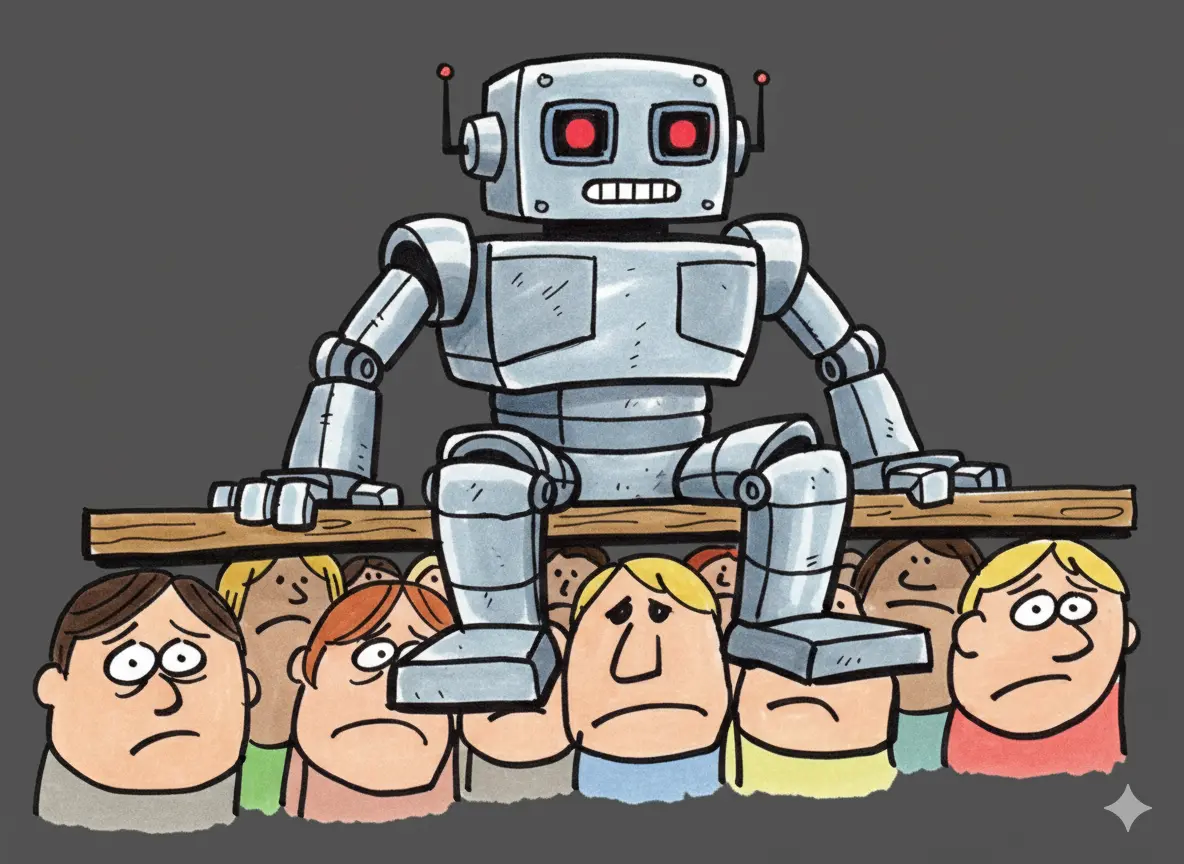

The Consumer-Last Reality

The irony of API-first design is that it often becomes consumer-last in practice. Teams spend weeks designing the perfect API specification, ensuring it follows all the REST conventions, implements proper versioning, and includes comprehensive error handling.

Then they throw it over the wall to the consumer teams with minimal documentation, no client SDKs, and zero consideration for how the API will actually be used.

The result? Consumer teams build wrapper APIs that transform the “perfect” API into something actually usable. They add caching, retry logic, error transformation, and pagination helpers. They essentially rebuild the API they wish they had received.

Breaking the Cycle

Escaping the consumer-last trap requires shifting from API-first to consumer-first thinking:

Start with the use cases, not the specification. Before writing a single line of OpenAPI, work with the consumer teams to understand what they actually need to build. What data do they need? What actions will they perform? What error states matter to their users?

Build client SDKs alongside the API. If your API is difficult to use without a wrapper, build the wrapper yourself. Provide first-party SDKs in the languages your consumers actually use.

Treat documentation as a first-class citizen. Documentation isn’t something you write after the API is complete, it’s how you design the API. If you can’t explain how to use an endpoint simply, the design is probably wrong.

Embrace pragmatism over purity. Sometimes REST principles need to be bent to meet real-world needs. A slightly less RESTful API that’s dramatically easier to use is better than a perfectly RESTful API that’s painful to consume.

The Way Forward

API-first design remains a valuable approach, but it needs a crucial amendment: API-first must mean consumer-first. The interface design should start with understanding the consumers’ needs, not with implementing technical specifications.

The best APIs aren’t the ones that follow every REST principle perfectly, they’re the ones that disappear into the background, allowing developers to focus on building their applications rather than wrestling with someone else’s interface design decisions.

Sometimes the most API-first thing you can do is ask: “Who’s going to use this, and what would make their life easier?”

That question might lead you away from textbook perfection, and toward something actually useful.