The Simplest Thing That Could Possibly Work Is Actually Insanely Hard

Why chasing architectural simplicity requires more engineering discipline than building complex distributed systems

The most radical approach to modern software architecture isn’t microservices or event-driven patterns, it’s doing the absolute minimum required to solve today’s problem. And it’s pissing off engineers everywhere.

When Simple Feels Like Cheating

Most engineers approach system design by imagining the “ideal” architecture: perfectly factored components, infinite scalability, elegant distribution patterns. They’re wrong. The real skill lies in understanding what you actually need right now and building exactly that, nothing more.

Consider rate limiting. The default impulse is to reach for Redis with a leaky-bucket algorithm. But the simplest thing might be in-memory tracking. Sure, you lose data on restarts, but does that actually matter for your use case? Could your edge proxy already handle this? The answer often reveals how much complexity we add because it feels more “professional.”

The Architecture of Underwhelming Solutions

Great software design looks boring. Unicorn, the Ruby web server, delivers request isolation, horizontal scaling, and crash recovery using nothing but Unix sockets and forked processes. The standard Rails REST API gives you CRUD operations in the most mundane way possible. These aren’t impressive software feats, they’re impressive design achievements because they do the simplest thing that could possibly work.

The pattern emerges: start with the absolute simplest approach, then extend only when new requirements force your hand. This isn’t laziness, it’s the ultimate application of YAGNI (You Aren’t Gonna Need It) as a design principle, prioritizing actual needs over theoretical elegance.

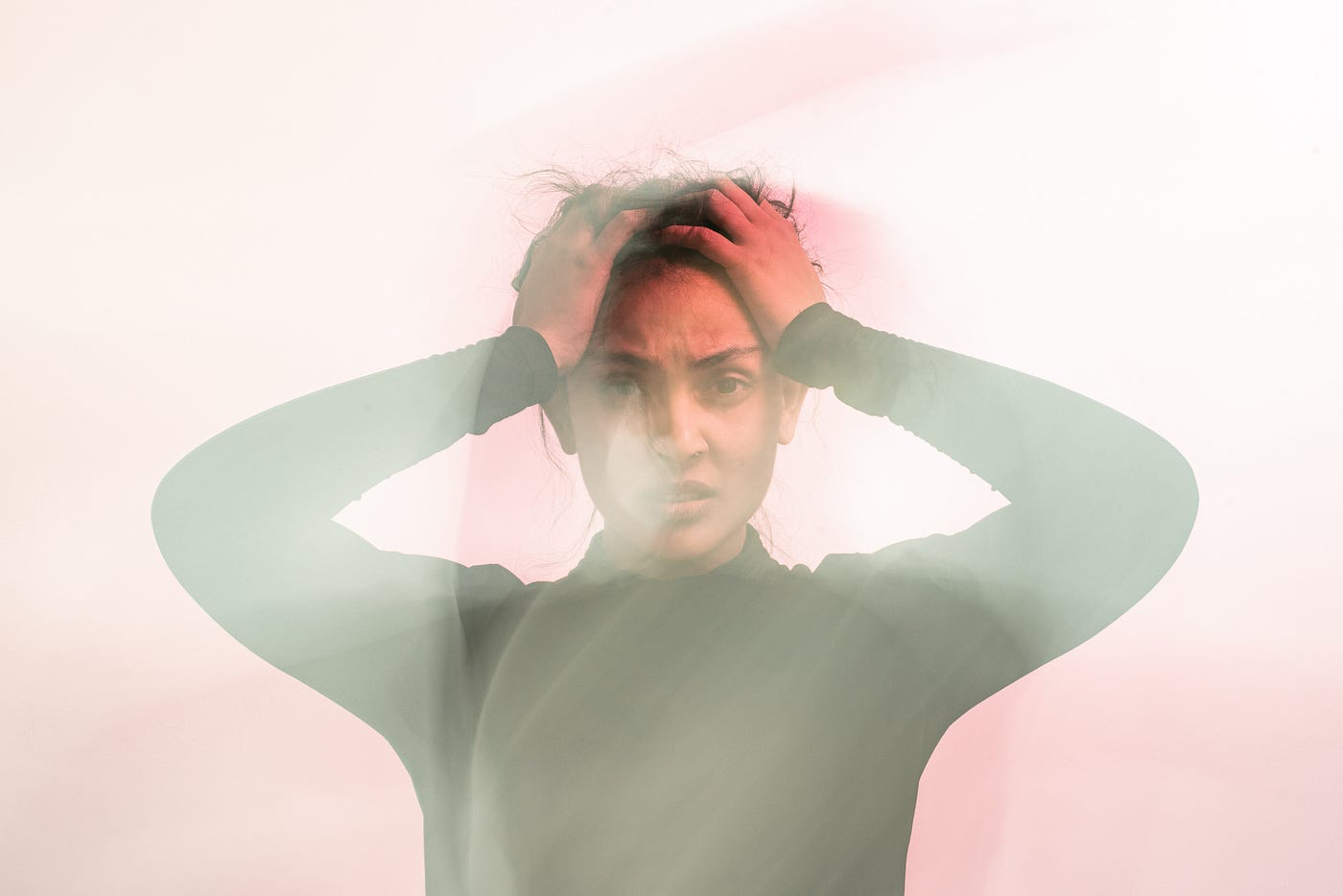

Why Simple Systems Infuriate Engineers

The backlash against simplicity comes from three legitimate concerns:

First, engineers worry about creating “big balls of mud” by not anticipating future requirements. But hacks and kludges aren’t simple, they’re just easier to think of. The proper fix usually requires understanding the entire system, making it fundamentally simpler than any quick workaround.

Second, there’s no consensus on what “simple” means. Is Unicorn simpler than Puma? Is in-memory rate limiting simpler than Redis? Simple systems have fewer moving pieces and less internal connectivity. They’re also more stable, if one approach requires more ongoing work without changing requirements, it’s inherently more complex.

Third, the scalability objection. Engineers scream “but in-memory rate limiting won’t scale!” Yet most systems never reach the scale where this matters. The cardinal sin of modern SaaS engineering is obsessing over scale that never materializes, creating inflexible systems that are harder to maintain than actually scaling would be.

The Domain Model as Complexity Containment

The real secret to simplicity isn’t doing less, it’s creating better boundaries. When invariants like “every order must have a shipping address” live in the domain model itself rather than scattered across service methods, you achieve actual simplicity through enforced consistency.

This approach treats all data as untrusted until it passes through domain rules, a zero-trust architecture for your business logic. The model becomes the gatekeeper, either admitting data into the valid world or rejecting it entirely. This structural enforcement is what makes simple systems actually work long-term.

The Prediction Problem Nobody Solves

The fundamental truth most architecture discussions ignore: we’re terrible at predicting where systems will go. It’s hard enough understanding where a system is today. Most design fails because it happens without that understanding.

There are exactly two ways to develop software: predict what your requirements might look like in six months and build for that, or build the best system for what you actually need right now. The first approach creates over-engineered monuments to imagination. The second creates systems that actually work.

When Simple Becomes the Hardest Choice

The irony of the simplest thing approach is that it demands more engineering discipline, not less. It requires deep system understanding, constant evaluation of actual versus theoretical needs, and the courage to build something that looks underwhelming on a architecture diagram.

The systems that follow this principle, Stripe’s clean dashboard, Notion’s content-first interface, Apple’s minimalist settings, aren’t simple because they’re primitive. They’re simple because they’ve removed everything that doesn’t serve the core purpose. And that removal requires more design skill than adding another service to your Kubernetes cluster.

The simplest thing that could possibly work remains the most controversial architectural approach because it forces engineers to confront the gap between what looks impressive and what actually works. In an industry obsessed with scale and complexity, choosing simplicity feels like heresy, which is exactly why it’s so effective.