Your Microservices Obsession is Killing Your Startup

A reality check for developers who reach for distributed systems before they've earned them

The uncomfortable truth about modern software architecture? You’re probably building microservices for all the wrong reasons. While Randy Sharp’s insightful perspective ↗ notes that “nobody starts with microservices”, a peculiar industry-wide amnesia seems to have taken hold. Companies that successfully scaled to microservices, Netflix, Amazon, Uber, didn’t start there, yet we’ve collectively decided to skip the first 99% of their journey.

The Case for Starting Simple

A monolithic architecture is a traditional software development model that uses one code base to perform multiple business functions according to Amazon’s characterization. It’s the architectural equivalent of living in a studio apartment, everything is within reach, and you don’t waste time navigating hallways between different rooms.

The math is brutally simple: AWS research suggests that “monolithic applications are easier to start with, as not much up-front planning is required” and “deploying monolithic applications is more straightforward than deploying microservices.” When you’re racing to find product-market fit, every minute spent architecting service boundaries is a minute not spent talking to customers.

As developer forums commonly note, the prevailing sentiment is that building a microservices app from scratch is extremely difficult when requirements change frequently, which they always do. Most founders don’t actually know what they’re building until they’ve built half of it wrong.

The Hidden Costs of Premature Distribution

The dirty secret of microservices? They’re often solving organizational problems, not technical ones. As one experienced developer noted, many companies adopt microservices “to solve people problems” rather than technical scaling challenges. Multiple teams can work simultaneously with less coordination overhead, but if you don’t have multiple teams yet, you’re paying for coordination infrastructure without the coordination problems.

Consider the operational overhead:

- Debugging requires “looking at multiple loosely coupled individual services” across distributed systems

- Deployment complexity increases exponentially with each additional service

- Infrastructure costs balloon when you need service discovery, API gateways, and distributed tracing from day one

- Team competency demands understanding of “cloud architecture, APIs, containerization, and other expertise specific to modern cloud applications”

The reality check comes from Sharp’s observation: “99% of the applications on the planet should be and should always continue to be written in a monolithic style.” Most startups fail, and from the few that do succeed, even fewer ever need to scale dramatically.

When Monoliths Actually Make Sense (Hint: Almost Always)

The monolithic approach shines in specific scenarios that happen to describe most early-stage companies:

For early-stage startups building MVPs, monolithic architecture provides the “fastest path to learning” according to practical guides. Single codebase deployment means you can iterate rapidly without coordinating multiple service deployments.

Smaller applications with limited domain complexity benefit from the unified approach. As the comparison shows, monoliths require “less planning at the start” and avoid the infrastructure overhead of distributed systems.

Teams with limited DevOps experience can focus on delivering value rather than wrestling with Kubernetes configurations and service meshes. The AWS guide notes that “developers new to distributed architecture” may find microservices challenging to troubleshoot.

The Psychology of Bad Architecture Decisions

Why do smart engineers make objectively poor architecture choices? Research reveals some uncomfortable truths about our decision-making processes.

A 2020 study by Larius Vargas and colleagues found that architecture decisions are often made without systematic evaluation. Instead, developers frequently rely on gut feeling, hype, or untested assumptions about future scalability, assumptions rarely grounded in actual requirements.

Even when we try to predict the future, studies show our decisions are clouded by cognitive biases like overconfidence, anchoring, and the illusion of control. We imagine ourselves building the next Netflix while building something that might not survive next month’s payroll.

The sunk cost fallacy kicks in early, we’ve invested so much in complex infrastructure that we’re reluctant to admit we over-engineered. One developer’s experience highlights this perfectly: “in my 12 or so years of experience, i never had a boss/customer who knew what they wanted or hadn’t changed requirements at least 5 times during the development.”

Building the “Service-Ready” Monolith

The sweet spot isn’t choosing between monolith or microservices, it’s building a monolith that can gracefully evolve into microservices when (and only when) necessary.

The key insight from practical implementation guides is to “design your ‘service-ready’ monolith” by structuring it as “a set of modules in one process, with strict boundaries and clean seams.” This means:

Organize code by business capability, not technical layers. Create clear modules like accounts/, catalog/, orders/ with their own controllers, domain models, and data access layers.

Stabilize module interfaces internally as if they were network calls. Use DTOs for requests/responses and avoid cross-module imports of private types.

Capture domain events even within the same process, training your system to be event-aware without paying the distributed systems tax.

Instrument from day one with request metrics by module, tail latency tracking, and correlation IDs through the stack. This data becomes crucial for making informed splitting decisions later.

Objective Signals for Splitting (Not Vibes)

So when do you actually need to graduate from your monolith? The trigger isn’t a feeling, it’s measurable evidence.

According to architecture playbooks, you should only consider splitting when two or more of these persist across sprints:

- Team throughput hits a coordination wall - Multiple teams keep stepping on each other because their modules change independently

- Hot path saturation - One module is CPU/IO heavy and drives vertical scaling, starving others

- Availability needs diverge - Critical paths need 99.95% uptime while less critical features can tolerate more downtime

- Change cadence diverges - Some modules deploy 10x more frequently and need faster approval windows

- Compliance requirements - Legal or runtime boundaries (PII, tenant isolation) justify separate blast radius

The Low-Drama Extraction Plan

When the evidence demands splitting, follow a phased approach that minimizes risk:

Phase 1: Strangle with internal boundaries - Create adapters so all callers use a consistent interface, then add contract tests to lock behavior.

Phase 2: Extract the codebase - Copy modules into new repos with their own CI/CD, maintaining the same API but behind a feature flag.

Phase 3: Dual-run shadow mode - Call both monolith and service paths in staging, comparing responses until they converge.

Phase 4: Gradual data migration - Provision separate databases, then incrementally migrate writes before reads.

Phase 5: Controlled cutover - Flip feature flags for small traffic percentages, watching p95/p99 latency and business KPIs like conversion rates.

As AWS demonstrates in their tutorial, this approach allows you to “break a monolithic application into microservices without any downtime” by carefully managing the transition.

Real-World Evidence: Who Actually Needs Microservices?

The case studies tell a consistent story: successful microservices adoption followed massive scale, not preceded it.

Netflix’s journey from monolithic Ruby on Rails to 700+ microservices happened after they were already serving millions of users globally. They didn’t start with distributed systems, they evolved into them when the monolith could no longer handle their growth.

Amazon’s “two-pizza team” model emerged as a cultural complement to microservices, not the other way around. Small autonomous teams owning individual services worked because they had the scale to justify the organizational structure.

The pattern is clear: companies that start with microservices are solving scalability problems they don’t have using organizational patterns they haven’t earned.

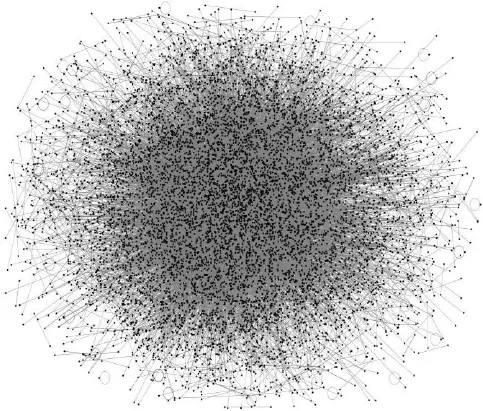

The Architecture Maturity Curve

Thinking about architecture as a progression rather than a binary choice changes everything:

Stage 1: Simple Monolith - Single codebase, rapid iteration, perfect for finding product-market fit

Stage 2: Modular Monolith - Clear boundaries, event-driven internally, service-ready structure

Stage 3: Selective Microservices - Extract only the components that genuinely benefit from independence

Stage 4: Distributed System - Full microservices architecture justified by scale and organizational needs

Most companies never progress beyond Stage 2, and that’s perfectly fine. As experienced architects note, “engineering is synonymous with essentialism” rather than complexity for its own sake.

The Bottom Line

Building for problems you’ll never face only adds unnecessary complexity and slows you down in the present. The most elegant architecture is the one that gets you to your next milestone with the least ceremony.

As one architect bluntly puts it: “Why even bother with the architecture which solves the problems that you will never get?” The companies that successfully scaled to microservices did so because they had scaling problems, not because they anticipated them.

Your startup’s competitive advantage isn’t having a more sophisticated architecture than your competitors, it’s having a working product while they’re still designing service meshes. Build what you need today, instrument everything, and let empirical evidence, not architectural fashion, guide your evolution.