Vertical Slices vs CQRS: The Architecture Debate That's Mostly Semantics

Cutting through the buzzword fog to reveal why these patterns are more similar than different and how semantic diffusion corrupts good ideas.

The software architecture community has been busy inventing new names for old ideas, and Vertical Slices Architecture might be the most successful rebranding since “cloud computing” replaced “someone else’s computer.”

The Great Architecture Rebrand

Jimmy Bogard’s 2018 Vertical Slices Architecture manifesto ↗ presented a radical idea: instead of organizing code by technical layers (controllers, services, repositories), organize by business features. Each feature gets its own vertical slice containing everything from API endpoint to database access.

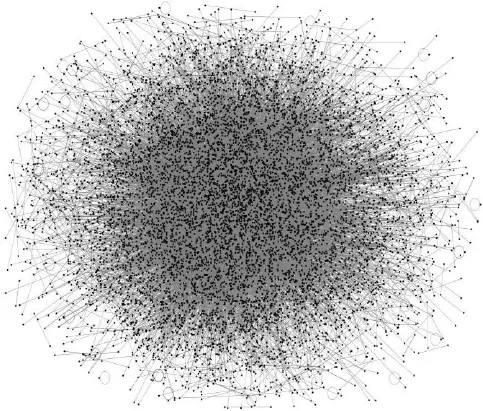

Meanwhile, Greg Young’s 2010 CQRS pattern ↗ advocated separating commands (state-changing operations) from queries (data retrieval). Both patterns essentially solve the same problem: preventing your codebase from turning into a tangled mess where changing one feature requires modifying seventeen different files across five directories.

The irony? VSA is essentially CQRS with better marketing. When you properly apply CQRS, you naturally drift toward Vertical Slices. The patterns reinforce each other, CQRS provides the conceptual split between commands and queries, while VSA provides the organizational principle.

Two Ways to Slice Your Codebase

Teams implementing these patterns typically follow one of two approaches:

Pure Vertical Slices where each feature is completely self-contained:

Slices with Thin Coordination where a facade handles cross-cutting concerns:

The pure approach gives maximum independence but risks duplicating authentication or error handling logic. The facade approach maintains consistency but introduces coupling points. Neither is objectively better, it depends on whether your team values isolation or consistency more.

How Good Ideas Get Corrupted

Here’s where things get spicy. Martin Fowler’s concept of “semantic diffusion” explains what happens when good ideas get passed through enough people that they lose their original meaning.

CQRS originally meant: separate commands and queries. That’s it.

Today, people think CQRS means:

- Two databases (nope)

- Event sourcing (optional)

- Eventual consistency (not required)

- Message queues (could be direct method calls)

- Complex distributed systems (works fine in a monolith)

The same corruption is happening to Vertical Slices. People now think VSA means:

- Zero shared code between slices (Jimmy said “minimize”, not “eliminate”)

- Separate database tables per slice (not required)

- Mandatory copy-paste (antipattern)

- Specific folder structures (missing the point entirely)

This semantic drift causes teams to reject useful patterns because they think they require complexity they don’t actually need. Teams build elaborate event-sourcing systems when all they needed was to put their queries in different files from their commands.

The CRUD Fallacy

“These patterns are too complex for CRUD systems”, complain developers who apparently haven’t read the actual definitions. Neither CQRS nor VSA require complex domain logic. They work perfectly fine for simple Create, Update, Delete operations, they just encourage you to name them OnboardUser, UpdateProductDefinition, and CancelSubscription instead of Create, Update, Delete.

This naming shift isn’t overhead, it’s the whole point. It forces you to think about what you’re actually building rather than blindly implementing database operations. When requirements inevitably evolve beyond simple CRUD, you’ve already established a structure that can handle complexity.

The debate between Vertical Slices and CQRS is mostly semantic. Both patterns address the same fundamental problem: organizing code around business capabilities rather than technical concerns. The real value isn’t in choosing one over the other, it’s in understanding what problems they actually solve rather than what the architecture influencers say they solve.

The most successful teams I’ve seen use CQRS for the conceptual separation and VSA for the organizational structure. They start simple and evolve their architecture as they learn more about their domain, rather than implementing elaborate systems for problems they don’t have yet.