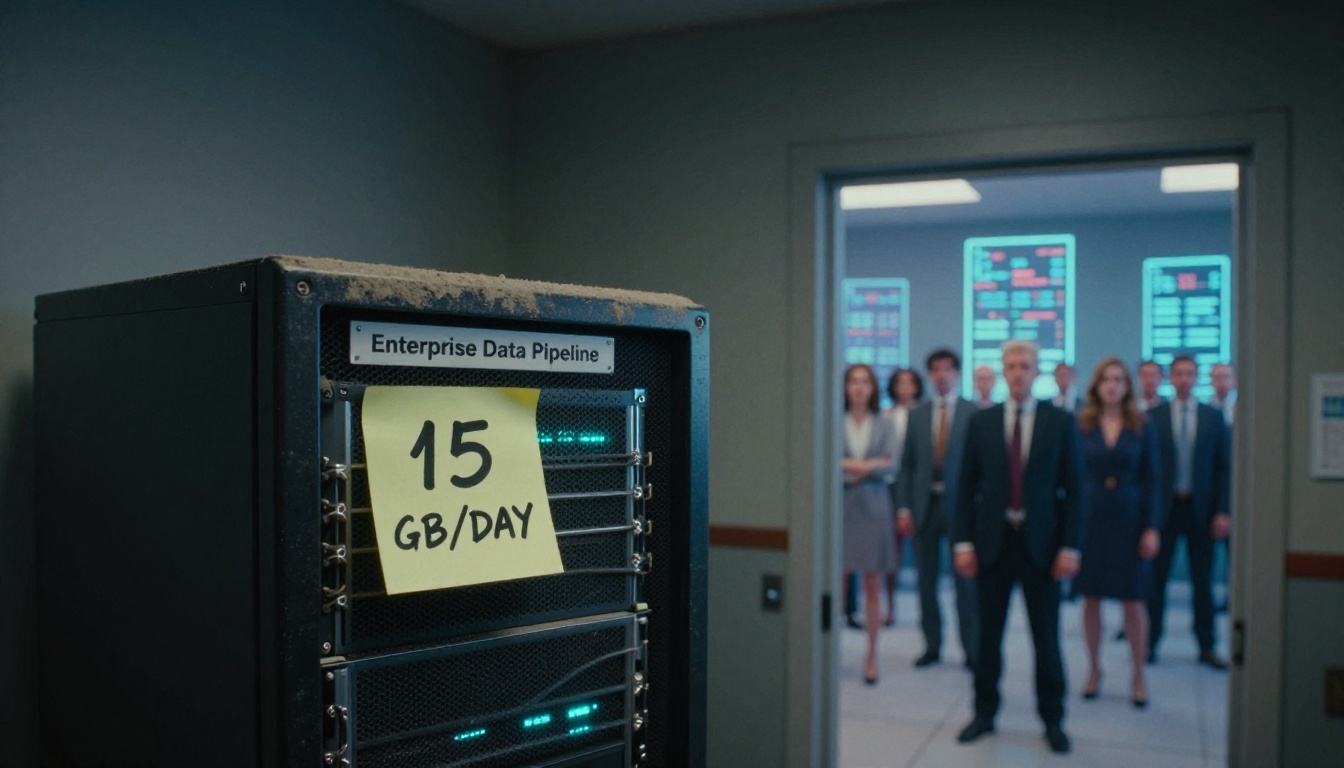

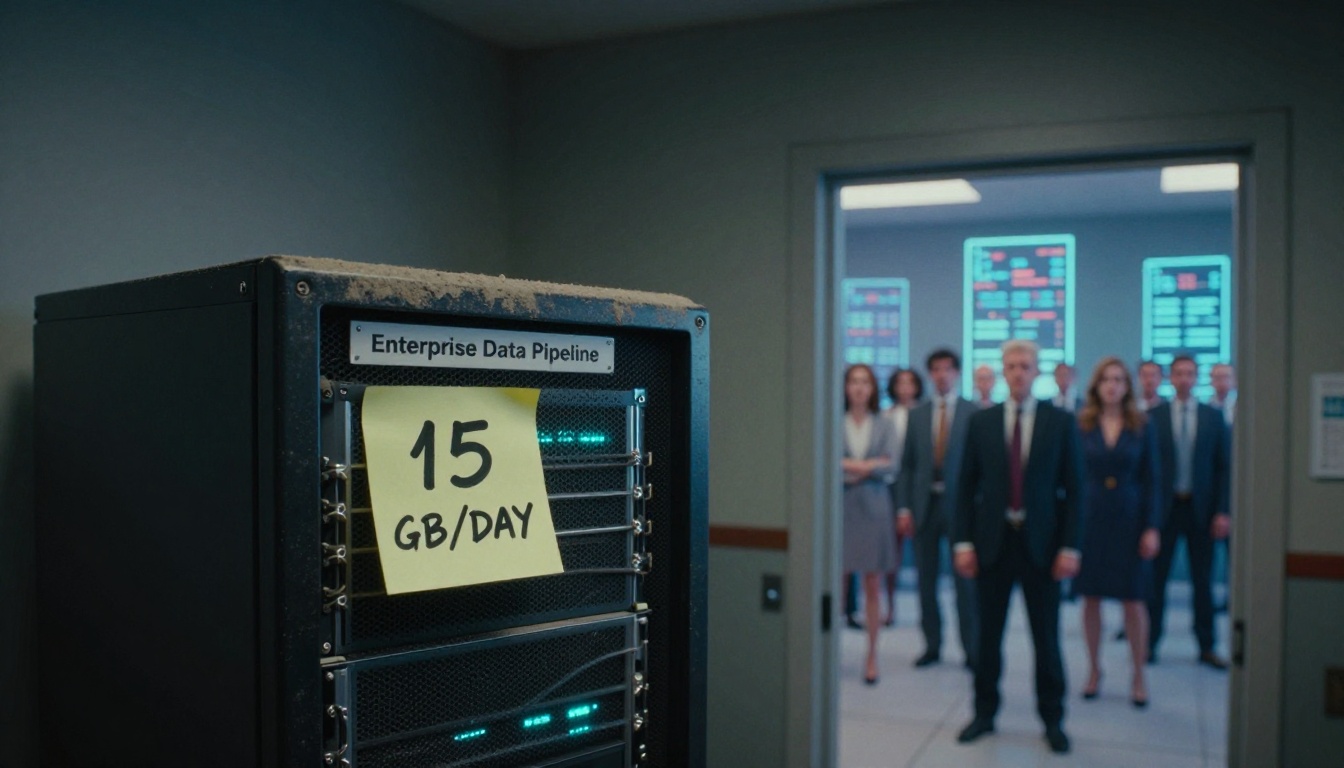

Your ‘Terabyte-Scale’ Data Pipeline Probably Processes 15 GB a Day

A data engineer with seven years in BFSI and pharma sparked an uncomfortable conversation last week: they’ve never seen incremental loads larger than 15 GB. Meanwhile, their LinkedIn feed is a parade of profiles claiming terabyte-scale expertise. The disconnect between reality and resume isn’t just inflation, it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what “big data” means in 2026.

The thread that followed reads like a therapy session for data engineers tired of being asked about their “petabyte experience” while troubleshooting 5 GB daily loads. The numbers tell a story that hiring managers and tool vendors don’t want to hear: domain dictates scale, and most domains aren’t as big as you think.

The 1, 15 GB Reality Check

The original poster’s experience mirrors what most enterprise data engineers see daily. BFSI and pharma, industries drowning in regulatory overhead, typically process 1, 15 GB incrementally. That’s not a failure of imagination, it’s a reflection of business reality. A bank’s daily transactions, a pharmaceutical company’s clinical trial updates, an insurance company’s claims processing, these generate data measured in gigabytes, not terabytes.

One commenter cut through the noise with a sobering perspective: “Data Architecture is not about the size, it’s about how you treat it.” They’d seen a client struggle with just 118 GB of total data. The problem wasn’t volume, it was architecture. This is where the industry’s obsession with scale misses the point. A poorly designed pipeline that can’t handle schema evolution or guarantee idempotency at 10 GB is just as broken as one that fails at 10 TB.

When “Big” Actually Means Big

The exceptions prove the rule, and they cluster in specific domains. Telcos operate in a different universe. One engineer described a large Indian telco ingesting ~100 GB every 10 minutes from raw log files, processed in mini-batch mode to Oracle. That’s 14 TB daily, real terabyte scale, driven by tens of millions of users making calls, sending texts, and consuming data.

E-commerce operates at similar scale when you count API call logs. One engineer processing transformed website analytics data reported 600+ million records per hour, roughly 1 TB hourly. What seemed like “big data” at 200 million records per day became routine infrastructure a year later.

Then there’s the hyperscale tier that most engineers will never touch. At Facebook, tables with 1, 2 PB per day per partition weren’t unusual, particularly for feed and ads data. The warehouse stood at 5 exabytes in 2022. Netflix operated at similar scale: 4.5 exabytes. These numbers aren’t just big, they’re incomprehensibly large, enabled by architectures that make enterprise data engineering look like child’s play.

Domain Is the Real Scalability Factor

The pattern is clear: industry vertical matters more than engineering skill. Telcos generate massive logs because every action, call, text, data packet, creates a record. E-commerce platforms track every click, hover, and API call to optimize conversion. Social media companies monetize every interaction through advertising.

BFSI and pharma operate differently. A financial transaction is a high-value event, not a firehose of telemetry. A drug trial produces careful, curated data, not streams of user behavior. The engineering challenges here aren’t about volume, they’re about correctness, compliance, and provenance. An idempotent pipeline that guarantees exactly-once semantics for 5 GB of financial transactions is more valuable than a flaky Spark job that “processes” 50 TB of logs.

This is why the recruiter obsession with “terabyte-scale” experience is so misguided. As one engineer lamented, “Unfortunately recruiters aren’t aware of it.” They’re screening for the wrong metric, optimizing for size when they should optimize for domain expertise and architectural rigor.

The Architecture Fallacy: Size Doesn’t Equal Complexity

The most revealing insight from the discussion isn’t about volume, it’s about treatment. A 15 GB daily load in pharma might involve complex SCD Type 2 dimensions, regulatory audit trails, and bi-temporal modeling. A 100 GB telco log dump might be a simple append-only operation with minimal transformation.

Layered data architectures for incremental data refinement demonstrate this principle. The medallion approach, Bronze, Silver, Gold layers, works at any scale, but its value isn’t in handling petabytes. It’s in creating clear contracts between ingestion, transformation, and serving. A 10 GB Bronze layer that feeds a carefully modeled Silver layer requires more architectural sophistication than dumping 10 TB into a data lake and calling it a day.

This is where tools like embedded analytics databases like DuckDB for efficient incremental processing change the game. DuckDB can process gigabyte-scale increments on a single machine faster than distributed systems can spin up clusters. The cost savings are dramatic, 70% reductions aren’t unusual, because you’re not provisioning infrastructure for theoretical max volume.

The Cost of Chasing Scale

The Databricks bill tells the real story. Cost and scalability challenges in large-scale data architectures hit small teams hardest. A two-person data team processing a billion transactions daily on EMR and S3 quickly discovers that “just glue some Lambda functions together” doesn’t scale economically. But here’s the dirty secret: most of those billion transactions are noise. The valuable signal might be 50 GB of aggregated insights.

This is why dimensional modeling trade-offs matter more than ever. Dimensional modeling trade-offs in modern data pipelines become critical when you’re paying per query. A star schema that worked fine on-premise becomes expensive in cloud data warehouses when you’re scanning petabytes to answer simple questions. Sometimes the answer isn’t better modeling, it’s questioning whether you need all that data in the first place.

Design-First vs. Scale-First Development

The AI code generation boom is making this worse. Design-first approaches to prevent drift in incremental data systems are no longer optional when Copilot churns out ETL pipelines at machine speed. The semantic drift, where generated code slowly diverges from business intent, scales with volume. A 5 GB pipeline with drift is fixable. A 50 TB pipeline with drift is a career-ending nightmare.

This is why idempotency patterns matter more than raw throughput. The ETL best practices that separate reliable pipelines from fragile ones, partition-based overwrites, transaction boundaries, explicit column selection, aren’t about handling scale. They’re about handling failure. When your 3 AM alert fires because a source schema changed, you want to re-run a pipeline and know it will produce correct results, not duplicate data.

-- Idempotent load: Replace the entire partition for the target date

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

DELETE FROM analytics.daily_revenue

WHERE report_date = '{{ ds }}';

INSERT INTO analytics.daily_revenue

SELECT

'{{ ds }}'::date AS report_date,

product_category,

SUM(order_total) AS total_revenue,

COUNT(DISTINCT customer_id) AS unique_customers,

COUNT(*) AS order_count

FROM raw.orders

WHERE order_date = '{{ ds }}'

GROUP BY product_category;

COMMIT;This pattern works whether you’re processing 10 GB or 10 TB. The difference is that at 10 GB, you can test it thoroughly. At 10 TB, you’re often testing in production.

The Hiring Paradox

For hiring managers, this creates a credibility gap. How do you evaluate a candidate who claims “petabyte-scale experience” when your pipeline processes 20 GB daily? The answer isn’t to chase the same scale, it’s to chase the same architectural discipline.

Ask about idempotency, not volume. Ask about schema evolution strategies, not cluster size. Ask about data validation frameworks, not throughput. The engineer who can explain how they guarantee exactly-once semantics for a 5 GB financial pipeline understands data architecture better than the one who brags about their 50 TB log dump.

Evolving data architectures and database choices at scale show that the smart money is on simplicity. PostgreSQL’s quiet dominance in 2025 wasn’t because it handles exabytes, it doesn’t. It won because it handles gigabytes to terabytes with rock-solid reliability, transactional guarantees, and an ecosystem that doesn’t require a PhD to operate.

What This Means for Your Next Pipeline

If you’re building incremental loads in 2026, stop optimizing for theoretical max scale. Start optimizing for your actual domain:

- Measure your increments: Most are 1-50 GB. That’s not small, that’s normal.

- Choose tools for your scale: DuckDB, PostgreSQL, or cloud warehouses handle this range efficiently. Don’t reach for Spark unless you have Spark-scale problems.

- Invest in architecture, not infrastructure: Idempotency, validation, and schema handling matter more than cluster size.

- Question volume assumptions: That 100 GB daily load might be 95 GB of noise. Aggregate upstream.

- Design for failure: The pipeline that fails gracefully at 10 GB will fail gracefully at 10 TB. The reverse isn’t true.

The terabyte-scale engineers aren’t lying, they’re just working in domains you’ll never encounter. And that’s fine. Your 15 GB pharma pipeline that guarantees audit compliance and data lineage is more valuable than their 15 TB log pipeline that produces vanity metrics.

Size isn’t the metric that matters. Treatment is.