For a generation of data engineers, Ralph Kimball’s The Data Warehouse Toolkit has occupied the same hallowed ground as the Gang of Four’s design patterns. The star schema wasn’t just a modeling technique, it was a moral imperative. Facts and dimensions, slowly changing dimensions, conformed dimensions: these weren’t architectural choices but commandments carved in stone.

But in 2026, that stone is cracking. The modern data stack, cloud data lakes, columnar engines like DuckDB, and increasingly sophisticated BI tools, has created a quiet rebellion. Data engineers are asking a heretical question: When does dimensional modeling become overengineering?

The evidence isn’t in conference keynotes but in Reddit threads where experienced engineers confess their doubts, in Slack channels where teams debate skipping the star schema for a flat table, and in production systems where a single denormalized table outperforms a perfectly modeled Kimball architecture. The tension between purist theory and pragmatic reality has never been sharper.

The Orthodoxy and Its Discontents

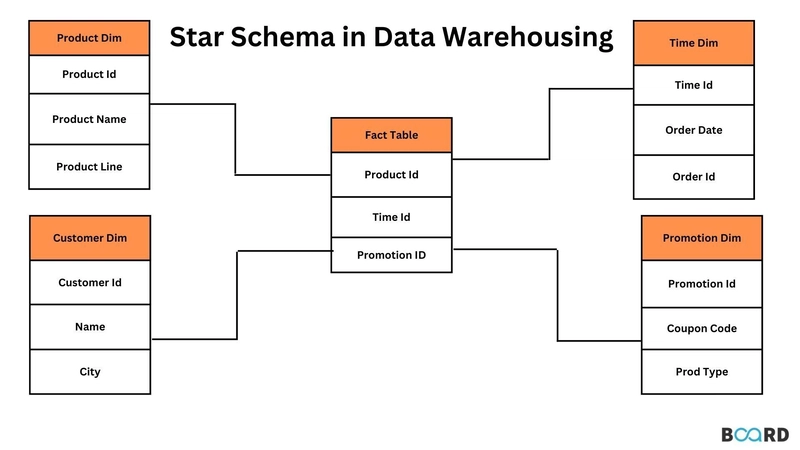

Dimensional modeling emerged in an era of expensive storage, limited compute, and primitive BI tools. The star schema’s genius was its optimization for read-heavy analytical workloads: denormalize dimensions to minimize joins, pre-calculate hierarchies, and create an intuitive structure for business users writing SQL.

The pattern is burned into our collective memory: a central fact table bristling with foreign keys, surrounded by dimension tables containing descriptive attributes. For enterprise-scale analytics, think billions of rows across dozens of business processes, this remains a robust foundation. But the modern data landscape has shifted dramatically:

- Storage costs have collapsed: Cloud object storage costs pennies per gigabyte, making redundancy economically viable

- Compute is elastic: Serverless query engines scale instantly, changing performance calculations

- BI tools grew smarter: Power BI, Tableau, and Looker can handle complex relationships and create semantic layers that abstract physical models

- Data volumes fragmented: Not every dataset is terabyte-scale, many "enterprise" solutions process mere millions of rows

These shifts expose a truth that Kimball’s disciples rarely acknowledge: dimensional modeling is a means, not an end. As one engineer bluntly put it in a recent discussion, "If the data is already organized, accessible, and every business question can be easily answered, then there is no need for a dimensional model."

The Gray Area Nobody Talks About

The Reddit thread that sparked this conversation perfectly captures the profession’s uncertainty. An engineer with seven years of experience admits defaulting to "should be a dim model" feedback, then questions whether this rigid stance is incorrect. Their colleague builds relational models that "logically star" but mix measures and attributes, arguing the data is too small to justify strict separation.

This isn’t incompetence, it’s pragmatism colliding with dogma. The gray area includes:

1. The "Five Tables, Millions of Rows" Problem

A sales dataset with five tables and under 100 million rows sits in an awkward middle ground. Building a full star schema means:

– Creating surrogate keys and ETL logic

– Managing slowly changing dimensions

– Maintaining referential integrity

– Documenting the model for stakeholders

Meanwhile, a flat table in Power BI with proper relationships might answer business questions in hours instead of days. The performance difference? Often negligible on modern hardware. As MotherDuck’s star schema guide notes, columnar databases like DuckDB handle joins efficiently, but they also crush simple aggregations on denormalized data. The optimization ceiling is higher than it was in 2005.

2. Ad-Hoc Analysis vs. Production Pipelines

There’s a crucial distinction between building a one-time analysis and constructing a permanent data product. For exploratory work, the overhead of dimensional modeling actively slows insight generation. A data scientist connecting directly to source tables, cleaning data in Polars, and visualizing in Power BI doesn’t need a conformed customer dimension, they need answers by end-of-day.

The operational analytics use case is even more compelling. When data engineers support real-time decision-making, fraud detection, inventory alerts, customer service routing, the rigid batch-oriented nature of dimensional models becomes a liability. Operational systems need normalized, transactional structures that support rapid updates, not denormalized analytical schemas optimized for historical analysis.

3. The Semantic Layer Abstraction

Modern BI tools have essentially created a new layer in the data stack. Power BI’s DAX engine, for example, can build a virtual star schema over a flat table. When you define measures and relationships in the semantic layer, you’re doing Kimball-style modeling, but at query time, not in physical tables.

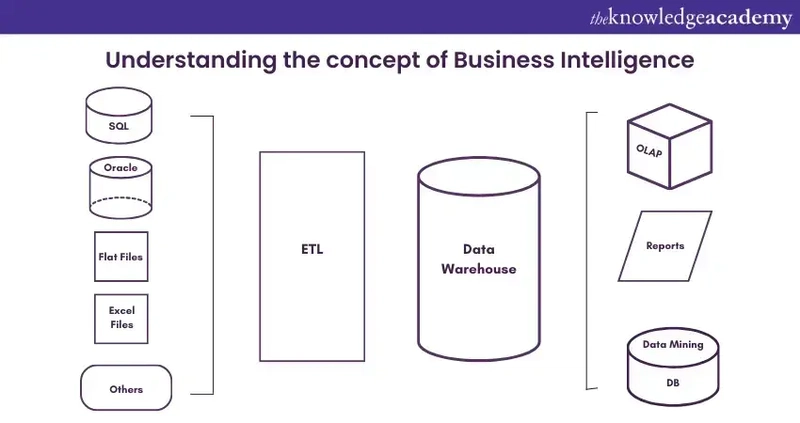

This approach flips the traditional workflow. Instead of ETL → Star Schema → BI Tool, teams increasingly do: Raw Data → BI Tool → Semantic Model. The "dimensional model" lives in Power BI, not Snowflake. For many SaaS companies where client data never crosses boundaries, this pattern eliminates the need for a physical star schema entirely.

When Dimensional Modeling Is Wrong

High-Frequency Transactional Writes

Star schemas are fundamentally OLAP designs. As MotherDuck’s guide explicitly warns: “Not for OLTP: Star schemas are optimized for read-heavy analytical workloads, not for high-frequency transactional writes.”

If your system requires rapid inserts, updates, and deletes, think user-generated content, IoT telemetry, or operational systems, the denormalized structure becomes a maintenance nightmare. Every dimension update requires cascading changes across fact tables. Normalized transactional models are the correct choice here, full stop.

The "One Big Table" Revolution

The debate over pragmatic vs. purist data modeling approaches has grown from whispered heresy to architectural movement. For many analytical workloads, a single denormalized table (OBT) outperforms star schemas:

- Simpler queries: No joins means analysts can’t get relationships wrong

- Better compression: Modern columnar formats achieve high ratios even with redundancy

- Faster development: Eliminates ETL complexity and surrogate key management

- Easier debugging: All data is in one place

Critics argue OBT wastes storage and complicates updates. But when storage is cheap and tables are append-only (event streams, click data), these concerns evaporate. A 400-column events table might feel wrong to Kimball purists, but it’s powering real-time dashboards at companies that value shipping over purity.

Ephemeral Data Products

That CSV sales file that arrives three times a year with unknown requirements? Building a full incremental ETL pipeline with slowly changing dimensions is architectural theater. Load it into Power BI, let stakeholders explore, and only model what proves valuable. Premature optimization wastes engineering cycles.

The Modern Decision Framework

So when shouldn’t you build a dimensional model? Use this practical checklist:

Skip the star schema when:

- Volume is low (< 100M rows) and query performance is acceptable

- Velocity is high, you need insights today, not next sprint

- Volatility is unknown, requirements are exploratory, not fixed

- Tooling is modern, your BI layer can handle relationships and calculations

- Writes dominate reads, the workload is operational, not analytical

- Data is client-isolated, no cross-tenant analysis required

- Team is small, engineering overhead exceeds analytical value

Build the star schema when:

- Enterprise scale, billions of rows, dozens of business processes

- Cross-functional analytics, shared dimensions across finance, sales, marketing

- Regulatory requirements, data governance and lineage tracking mandatory

- Self-service BI, business users need intuitive, well-documented structures

- Performance at scale, queries must run in seconds, not minutes

The Uncomfortable Truth

Bill Inmon’s recent critique of modern data warehouse practices argued that treating storage as a substitute for integration reduces data warehousing to "rubble." He’s not wrong, but he’s also not entirely right.

The modern data stack hasn’t eliminated the need for thoughtful modeling, it’s shifted where that modeling happens. The choice isn’t between Kimball and chaos, it’s between physical modeling, semantic modeling, and ephemeral modeling based on context.

Dimensional modeling isn’t dead. For enterprise-scale analytics, it’s still the gold standard. But treating it as a universal solution is cargo cult engineering. The best data engineers know when to reach for Kimball’s patterns and when to leave the book on the shelf.

The real heresy isn’t questioning dimensional modeling, it’s pretending that one technique solves every problem in a landscape that’s changed beyond recognition.

Next Steps for Your Architecture:

- Audit your current models against the decision framework

- Pilot a flat-table approach for a low-volume, exploratory use case

- Measure actual query performance, not theoretical benefits

- Build semantic layer skills in your BI team to reduce physical modeling overhead

- Document when and why you choose each pattern, context matters more than compliance

The star schema will always have a place in data engineering. But that place isn’t everywhere, and admitting that is the first step toward architectural maturity.