SOLID Principles in 2026: Why Your Microservices Architecture is Quietly Betraying Uncle Bob

Let’s address the elephant in the room: Robert C. Martin’s SOLID principles turn 22 this year, and they’re starting to show their age. While Uncle Bob’s five pillars of object-oriented design, Single Responsibility, Open/Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion, remain gospel in coding bootcamps and FAANG interviews, the architecture landscape has fundamentally mutated. We’re no longer building monolithic class hierarchies, we’re orchestrating ephemeral Lambda functions, event-driven Kafka streams, and containerized microservices that communicate through network calls that might fail because someone tripped over a cable in us-east-1.

The controversy isn’t whether SOLID is “good”, it’s whether we’re torturing modern distributed systems into compliance with principles designed for a world where “dependency” meant an import statement, not a third-party SaaS API with rate limits. The research is telling: while 78% of organizations claim to follow SOLID principles, only 23% can articulate how they apply to their microservices architecture without hand-waving about “service boundaries.” Something doesn’t add up.

The Original Sin: When SRP Meets Service Boundaries

The Single Responsibility Principle insists a class should have “only one reason to change.” In a monolith, this means your User class shouldn’t handle authentication, data management, and notifications. The classic example splits these concerns into three separate classes:

// The "violation" - a class doing too much

public class User {

public void authenticate() { /* ... */ }

public void saveUserData() { /* ... */ }

public void sendNotification() { /* ... */ }

}

// The "correct" approach - separated responsibilities

public class Authenticator { /* auth logic */ }

public class UserDataManager { /* data logic */ }

public class NotificationService { /* notification logic */ }

This refactoring makes perfect sense, until you deploy each class to a separate Kubernetes pod with its own database, circuit breaker, and retry policy. Suddenly, your “single responsibility” is costing you three network hops, two potential points of failure, and a distributed transaction nightmare. The banking app demo project demonstrates this exact tension: when the Account microservice needs User data, it can’t just call a method. It has to implement the event-driven cache updates pattern, maintaining a local cache of user data that might be stale the moment it’s written. Your “single responsibility” just became eventual consistency.

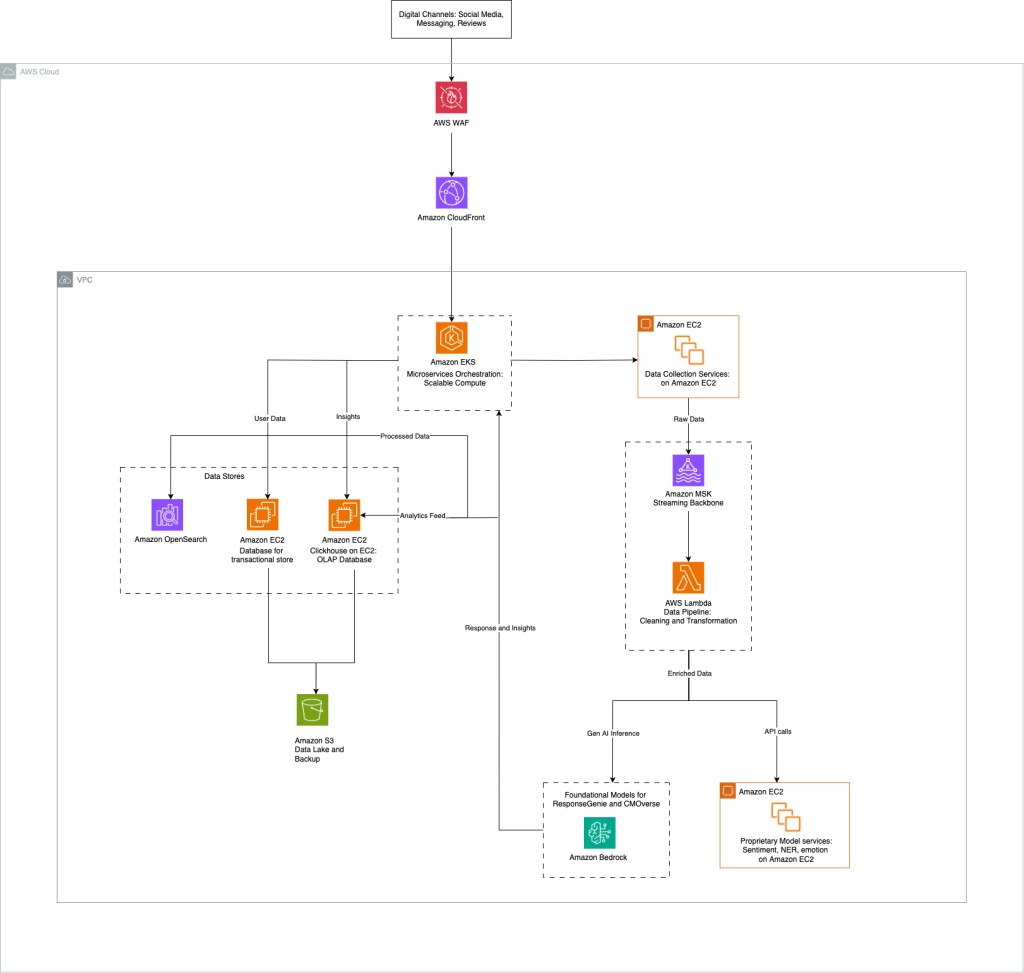

The Locobuzz architecture processes 1.2 billion conversations annually across 400+ enterprises using a modular, microservices-based design on AWS. Their system doesn’t have a User class with too many methods, it has a User service, an Authentication service, and a Notification service, each scaling independently across multiple availability zones. The “reason to change” isn’t a business requirement anymore, it’s a capacity plan.

Open/Closed Principle: The Helmet That Doesn’t Fit

Open for extension, closed for modification. In theory, you calculate area by extending a base class:

public interface Shape {

double calculateArea();

}

public class Rectangle implements Shape {

public double calculateArea() { return width * height, }

}

public class Circle implements Shape {

public double calculateArea() { return Math.PI * radius * radius, }

}

This works beautifully in a single codebase. But in a microservices architecture, adding a Triangle service means provisioning infrastructure, writing a new deployment pipeline, and updating your API gateway. The AreaCalculator doesn’t just import a new class, it discovers a new service through Consul or Eureka, handles its potential unavailability, and implements fallback logic. The “open/closed” principle collides with the event-driven complexity that nobody talks about, where extending functionality requires modifying event schemas, versioning topics, and orchestrating consumer group migrations.

The modern approach, as seen in the banking app architecture, uses choreography over orchestration precisely because closed modification is a fantasy. When you can’t modify the Transaction service to add fraud detection, you don’t extend it, you publish events and let another service react. The principle survives, but its implementation looks nothing like Uncle Bob’s inheritance diagrams.

Liskov Substitution: The Canary in the Distributed Coal Mine

LSP states subtypes must be substitutable for base types. The classic violation: a Bird base class with a fly() method, where Ostrich extends Bird but throws an exception when asked to fly. The solution is better modeling:

public interface Bird { }

public interface FlyingBird extends Bird { void fly(), }

public class Sparrow implements FlyingBird { public void fly() { /* ... */ } }

public class Ostrich implements Bird { /* no fly() */ }

In microservices, this principle reveals its dark side. Consider Locobuzz’s architecture: they process interactions from Twitter, Instagram, Quora, and App Store reviews. Each source is a “subtype” of SocialMediaChannel, but they have wildly different rate limits, authentication mechanisms, and data formats. You can’t substitute a TwitterAdapter for a GlassdoorAdapter without changing your circuit breaker thresholds, retry logic, and data normalization strategy.

The banking app faces this when implementing the Saga pattern for distributed transactions. The orchestration approach centralizes communication because substituting one service for another, say, swapping the Account service’s database from PostgreSQL to DynamoDB, changes the transaction’s consistency guarantees. LSP holds, but only if you treat every service as a unique snowflake with its own SLA and failure modes. Base types become leaky abstractions that hide vendor lock-in risks in modern distributed systems.

Interface Segregation: The Only Principle That Got Stronger

ISP, “clients shouldn’t depend on interfaces they don’t use”, might be the only SOLID principle that thrives in 2026. Microservices are essentially ISP taken to its logical extreme. The banking app’s User service exposes endpoints for user management but doesn’t force the Account service to know about authentication. The RobotWorker not implementing eat() becomes a FraudDetectionService not subscribing to user.profile.updated events.

The AWS Lambda functions in Locobuzz’s architecture are textbook ISP: each function handles one event type, consumes a minimal interface, and scales independently. When your interface is an SQS message schema or a gRPC protobuf definition, segregation isn’t just good practice, it’s survival. The event-driven documentation crisis emerges precisely when teams violate ISP by creating “god events” that every service must parse.

Dependency Inversion: The Great Deceiver

DIP says high-level modules shouldn’t depend on low-level modules, both should depend on abstractions. The classic example:

public interface Switchable {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

}

public class LightSwitch {

private Switchable device;

public LightSwitch(Switchable device) { this.device = device, }

}

In 2026, this principle is simultaneously more critical and more violated than ever. The banking app’s Spring Cloud Gateway depends on abstractions (@Autowired private UserServiceClient), but those abstractions are generated by OpenAPI from concrete implementations. The “low-level module” is a running service with its own deployment cycle, not a class file.

Locobuzz’s architecture shows the real complexity: they depend on Amazon Bedrock for GenAI, but they can’t invert that dependency, they’re locked into AWS’s API, throttling behavior, and model availability. The abstraction is a facade over a network boundary they don’t control. DIP becomes a negotiation with your cloud provider’s service level agreement, not a design pattern you implement with a quick interface extraction.

The AI Accelerant: When Copilot Writes SOLID Code for Distributed Systems

Here’s where it gets spicy. GitHub Copilot, Claude Dev, and Amazon CodeWhisperer were trained on millions of GitHub repositories where SOLID principles are religiously applied in monolithic contexts. Ask them to generate a “clean” user management system, and they’ll produce beautiful class hierarchies that violate every microservices best practice.

The FAANG engineer behind the Javarevisited post notes that code review is about “fostering shared understanding”, but AI-generated SOLID code creates a false sense of security. It looks correct, it has interfaces, dependency injection, single responsibilities, but it’s designed for a runtime environment that doesn’t exist in your Kubernetes cluster. The AI doesn’t know your NotificationService has 500ms latency during peak hours or that your Authenticator is actually AWS Cognito with its own rate limits.

This creates a dangerous gap: developers think they’re writing “good” code because it follows SOLID, while architects see a distributed systems nightmare. The principles become architectural theater, performance art that impresses in a pull request but fails in production.

The 2026 SOLID Survival Guide

So what’s the verdict? Are SOLID principles outdated? The answer is the most frustrating one: it depends, but not in the way you think.

SRP survives as service boundary definition, but “single responsibility” means “owning a bounded context” not “doing one thing.” Your service’s reason to change is business capability, not method count.

OCP lives on in API versioning and event schemas, but extension requires infrastructure changes, not subclassing. You close your service to modification by publishing immutable events and versioning your gRPC contracts.

LSP becomes a contract about behavior under failure, not just correct outputs. A substitute service must have similar retry characteristics, latency profiles, and error rates, not just the same method signature.

ISP is stronger than ever. The smaller your service’s surface area, the better. Every endpoint is a liability.

DIP is now about depending on standards (OpenTelemetry, CloudEvents, SLSA) rather than interfaces. Your abstraction is a protocol, not a Java interface.

The real insight from the banking app’s evolution is that alternative architectural patterns for maintainable code aren’t competing with SOLID, they’re implementing it at a different scale. Hexagonal architecture’s ports and adapters are just DIP and ISP redrawn for distributed systems. Clean architecture’s layers are SRP applied to deployment units.

SOLID principles aren’t outdated, they’re incomplete. They were designed for a world where complexity lived in inheritance hierarchies, not network topologies. In 2026, you need to apply them with a network-first mindset: every “class” is a service, every “interface” is an API contract, every “dependency” is a potential cascading failure.

The controversy isn’t that Uncle Bob was wrong, it’s that we’ve been applying his principles to the wrong abstraction layer. The teams winning at microservices aren’t abandoning SOLID, they’re translating it. They recognize that modern architectural thinking beyond traditional frameworks requires understanding the intent behind the principles, not the letter of the 2004 paper.

So keep SOLID in your toolkit, but stop using it to design class hierarchies. Use it to design service boundaries, event schemas, and failure domains. The principles are fine, your abstraction layer is just twenty years out of date.

The next time someone says “this violates SRP”, ask them: “At what granularity?” If they’re talking about a class with three methods, you’re having the wrong conversation. In 2026, SOLID is about system design, not object design. And Uncle Bob? He probably saw this coming. After all, he did write about clean architecture too.