Legacy Rewrites Don’t Fail From Bad Code, They Fail From Ego

You’ve spent two years convincing leadership to let you rewrite the legacy Rails monolith. The one that’s been limping along since 2014, processing actual money, with zero tests and files half the team refuses to touch. You won. You got approval. And now everyone’s frozen with terror.

This isn’t analysis paralysis. It’s the sudden realization that you have no idea what “working” actually means.

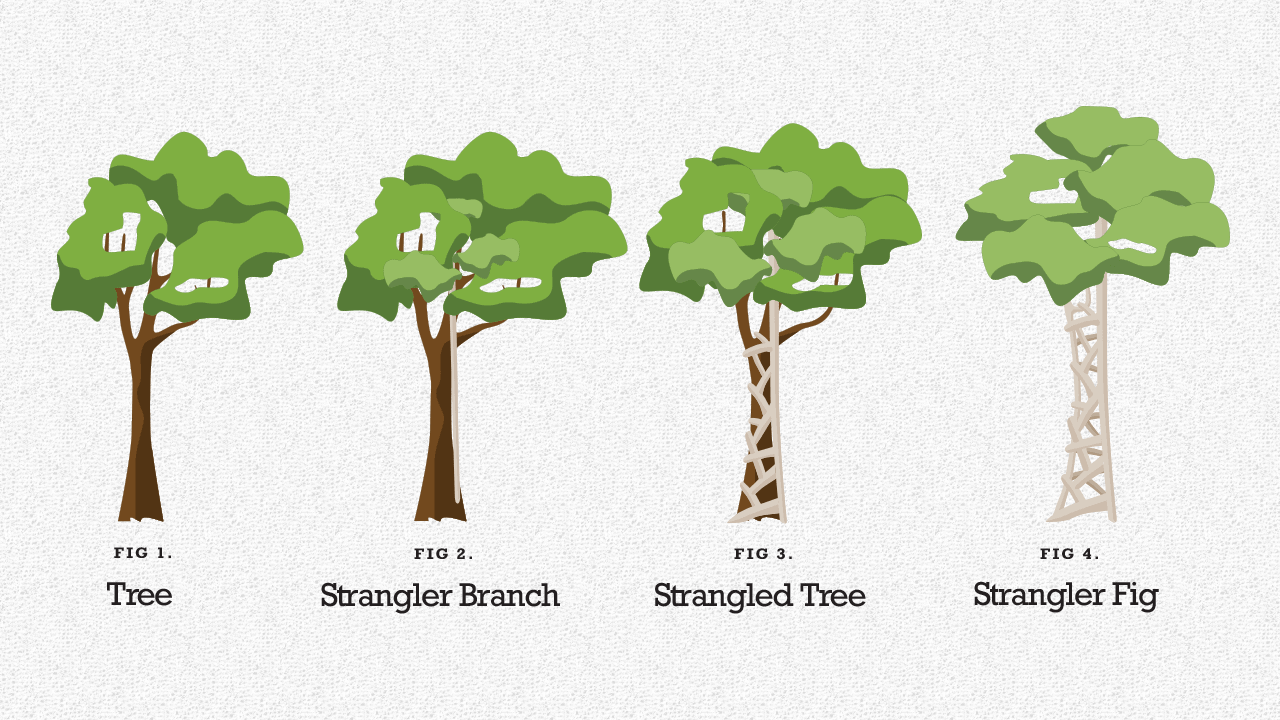

The Reddit thread that kicked off this discussion captures the moment perfectly: a team staring at their newly-approved rewrite project, realizing the gap between “our code is bad” and “we understand exactly what this system does.” The top-voted advice, cover flows with end-to-end tests, use the strangler fig pattern, migrate piece by piece, sounds reasonable until you’re the one holding the production database credentials at 2 AM.

The $800K Mistake of Defining “Better” Wrong

Before we talk about what works, let’s examine what doesn’t. One team split their monolith into 12 microservices and watched their response time balloon from 100ms to 3 seconds. Their AWS bill tripled. They burned $800K in runway and lost engineers who “didn’t sign up to be distributed systems engineers.” The punchline? Their original monolith was handling 50,000 requests/day just fine.

The problem wasn’t the rewrite, it was the justification. A new VP from Netflix pitched microservices as the path to “100 million users”, and nobody asked the obvious question: We have 50,000 users. Why are we optimizing for a scale problem we don’t have?

This is the first rule of safe rewrites: your current system is already solving a problem. Maybe not elegantly, maybe not efficiently, but it’s handling real transactions, real users, real money. If you can’t articulate exactly what “working” means in that context, your rewrite is doomed before you write a single line of code.

Characterization Tests: The Unsexy Foundation That Actually Works

Michael Feathers’ insight that “legacy code is just code without tests” reframes everything. You’re not dealing with bad code, you’re dealing with code that can’t be changed safely. And that’s a solvable problem.

Characterization tests are your microscope. They don’t test what the code should do, they document what it actually does. For a financial transaction system, this means:

- Capture real production traffic (sanitized, of course)

- Record inputs and outputs for every critical path

- Write tests that lock down current behavior, bugs and all

- Run these tests against the old and new systems in parallel

The Reddit commenters who recommended this approach were onto something, but they missed the critical detail: characterization tests aren’t a one-time task. They’re your safety net for the entire migration. When your new system produces a different result, you need to know whether you’ve discovered a bug in the old system or introduced one in the new.

The Strangler Fig Pattern: Death by a Thousand Feature Flags

The strangler fig pattern, gradually replacing parts of the old system by routing requests through a facade, works because it contains failure. But teams get this wrong by treating it as an architecture pattern instead of a risk management strategy.

Here’s how to do it right for critical systems:

Start with the edges, not the core. Don’t begin with payment processing. Start with email notifications, analytics logging, or PDF generation, things that can fail without losing customer money.

Use feature flags as circuit breakers, not just toggles. When the new system fails, you need to fall back to the old system automatically. One team’s payment service double-charged customers because their feature flag was manual. Another team’s inventory service used a flag that automatically rolled back after three failures in five minutes. Guess which one kept their customers?

Delete migrated code immediately. The commenter who said “just make sure to delete from the old once you’ve happily flipped to the new” was right, but “happily” needs a definition. For financial systems, “happily” means running in production for at least two billing cycles with zero discrepancies in your reconciliation reports.

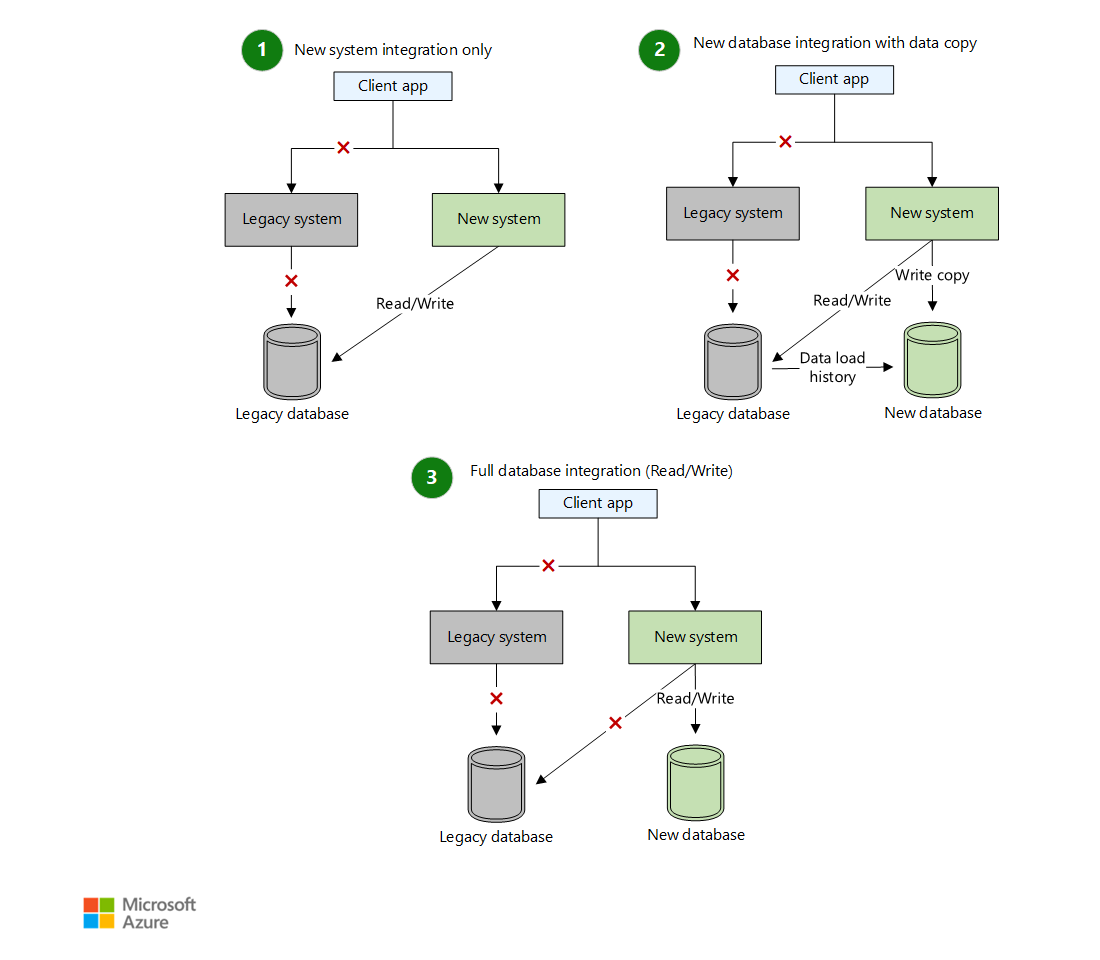

Dual Running: The Strategy Nobody Wants to Pay For

Running both systems in parallel is the safest approach and the hardest to justify. It doubles your infrastructure costs and requires engineering discipline that most teams lack. But for systems that process “actual money”, it’s the difference between a smooth migration and a resume-generating event.

The key is narrowing the comparison surface. You don’t need to compare every database field. You need to compare:

- Financial summaries: Does the new system produce the same daily totals?

- Audit trails: Are all actions logged identically?

- Error rates: Are you seeing new failure modes?

- Performance: Is the new system within acceptable variance?

One team processing insurance claims ran both systems for six weeks. They compared every claim’s financial outcome, flagging discrepancies for manual review. They found 47 cases where the old system had been calculating premiums incorrectly for three years. The rewrite didn’t just replace the system, it fixed bugs nobody knew existed.

The “Boring” Truth About What Actually Works

After the microservices disaster, the team that went back to their monolith discovered something profound: their original system wasn’t slow because of architecture. It was slow because of missing database indexes and lack of caching.

Before you rewrite, do the boring things:

- Add proper monitoring (New Relic APM, DataDog, etc.)

- Fix slow queries (the SQL Performance Cheatsheet identified real bottlenecks)

- Implement read replicas for heavy read traffic

- Improve caching with proper invalidation strategies

- Scale vertically before scaling horizontally

Their “boring” optimizations got their p50 response time from 450ms back to 110ms. Their AWS bill dropped to one-third of the microservices architecture. Their team stopped quitting.

When Rewrites DO Make Sense

Let’s be clear: sometimes you really do need to rewrite. But the criteria aren’t technical, they’re business-driven:

Rewrite when:

– The technology stack is end-of-life and unsupported (Rails 2 in 2025)

– Regulatory requirements mandate changes the architecture can’t support

– The system has genuinely hit scaling limits after optimization

– The team overhead of maintaining the old system exceeds the cost of migration

Don’t rewrite when:

– The code is just “ugly” but functional

– You’re “preparing for scale” you don’t have

– A new VP wants to “modernize” without specific business justification

– You think it will make development faster (it won’t, for at least a year)

The Real Plan for the Paralyzed Team

Back to that Reddit post. The team is frozen because they’re smart enough to know that “processing actual money” means they can’t afford to be wrong. Here’s what they should do:

Week 1-2: Define “Working”

– Document every financial reconciliation process

– Identify which failures are reversible vs. catastrophic

– Get agreement from finance, compliance, and product on success criteria

Week 3-6: Build Your Safety Net

– Implement characterization tests for the top 10 critical flows

– Set up parallel running infrastructure (even if you don’t use it yet)

– Create automated reconciliation scripts that compare old vs. new

Week 7-12: Migrate the Edges

– Start with read-only operations (reporting, analytics)

– Move to idempotent operations (email sending, logging)

– Finally tackle the core transactional logic

Month 4-6: Prove It

– Run parallel for at least one full billing cycle

– Compare financial outcomes daily

– Roll back automatically on discrepancies

The commenter who said “pushing for a rewrite without a plan is risky” was right. But the real risk isn’t technical, it’s that you’ll spend six months building something that doesn’t solve the business problem the old system was solving.

The Uncomfortable Conversation You Need to Have

The microservices team had a moment of clarity in month seven. Their VP wanted to add more complexity to fix the complexity. The CFO asked, “Can we go back?” The VP said that would be admitting failure. The engineer replied, “We’re already failing. Going back would be admitting reality“.

Before you start your rewrite, have that conversation. Define what failure looks like. Define what success looks like. And most importantly, define the conditions under which you’ll stop and go back.

Because the real secret to safe rewrites isn’t technical. It’s the courage to admit when the old system, spaghetti code and all, is actually better than the new system you’re building.