You’re reading your HSBC statement email when a physical letter arrives claiming your emails are “returned undelivered.” The absurdity would be comical if it weren’t a terrifying window into how fundamentally broken enterprise email infrastructure has become. This isn’t a minor glitch, it’s a systemic failure where a global bank conflates surveillance capitalism with basic protocol literacy, exposing architectural fragility that should keep CTOs awake at night.

The $200 Billion Bank That Doesn’t Understand Email

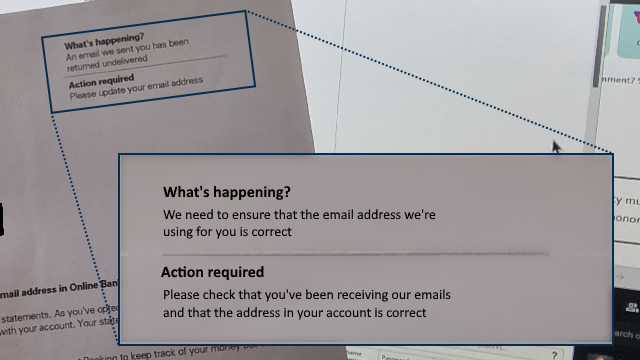

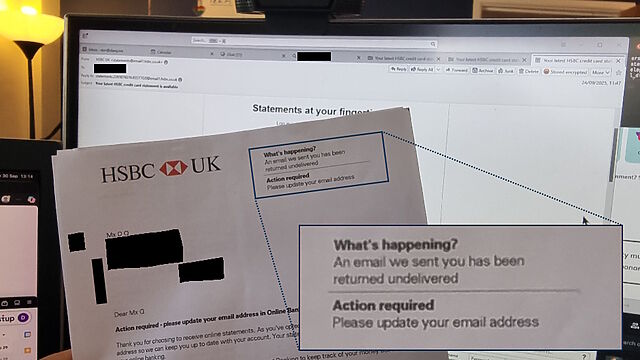

The story starts simply: Dan Q receives his monthly HSBC credit card statement via email, as he has for months. Then comes the paper letter, sternly warning that emails are bouncing and action is required. The problem? The emails are sitting right there in his inbox, marked as read. The email address in his account is correct. Nothing is broken, except HSBC’s understanding of how email infrastructure works.

When Dan contacts HSBC’s customer service, the interaction devolves into theater of the absurd. The agent named Ankitha insists that “if the bank has sent the letter, you will have to update the e-mail address”, a circular logic that treats the bank’s own flawed process as irrefutable evidence. The phone support eventually admits the truth: if the address is correct, ignore the letter. But by then, the damage is done. The bank has demonstrated that its left hand doesn’t know what its right hand is doing, and neither hand understands the underlying technology.

This isn’t isolated. The same pattern appears across enterprise systems, where outdated automation practices expose systemic risk. Companies build brittle infrastructure on misunderstood protocols, then layer on monitoring that measures the wrong things entirely.

Tracking Pixels: The False Prophets of Deliverability

The smoking gun hides at the bottom of HSBC’s emails: two 1×1 tracking pixels served over unencrypted HTTP.

<img src="http://www.email1.hsbc.co.uk:8080/Tm90IHRoZSByZWFsIEhTQkMgcGF5bG9hZA=="

width="1"

height="1"

alt="">

These Base64-encoded payloads (Tm90IHRoZSByZWFsIEhTQkMgcGF5bG9hZA== decodes to “Not the real HSBC payload”) are surveillance mechanisms masquerading as analytics. When your email client loads these images, HSBC gets a ping. No ping? HSBC assumes you never got the email.

This assumption is architecturally bankrupt for several reasons:

-

Privacy tools block these by default. Modern email clients disable remote image loading precisely to prevent this tracking. Apple Mail, ProtonMail, and many others make this the default behavior.

-

HTTP leaks data to the network. That unencrypted connection means anyone on your WiFi, at a café, airport, or office, can see you’re banking with HSBC and reading their emails. For a financial institution, this is security malpractice.

-

Email firewalls prefetch images. Enterprise email security often pre-fetches images to scan for malware, triggering tracking pixels before humans ever see the message. This creates false positives.

-

Accessibility tools don’t load images. Screen readers and text-only clients ignore these pixels, creating false negatives for disabled users.

The bank has mistaken a statistical proxy for individual verification. Tracking pixels can tell you approximately what percentage of recipients opened an email across a campaign. They cannot tell you whether a specific person received a specific message. Using them this way is like measuring website traffic to verify that a particular customer paid their bill, wrong tool, wrong level of abstraction.

This is the same category error that drives legacy architectural failures. Teams build systems that measure what’s easy to measure, not what matters. Then they optimize for the metric until the metric becomes the mission.

The Darkest Timeline: When Surveillance Becomes the Default

The most damning part? HSBC’s system is designed so that blocking surveillance triggers an “undeliverable” flag. If you protect your privacy, the bank assumes you’re unreachable. This is surveillance capitalism achieving its final form: privacy becomes a bug, not a feature.

As Dan Q notes, this puts us in the “darkest timeline”, a world where the bank cannot conceive that customers might block tracking. Their letter essentially reads: “We cannot conceive that there’s anybody left who hasn’t given up on trying to fight back against surveillance capitalism. Action required: turn off your privacy software so we can watch you read our emails.”

This reveals a deeper rot in enterprise architecture: frameworks without practice. The Info-Tech Research Group recently highlighted how enterprise architecture fails when frameworks take priority over practical design. HSBC has likely ticked every compliance box, passed every audit, and documented its email architecture in pristine Visio diagrams. Yet none of that prevented a fundamental misunderstanding of how SMTP, DNS, and email clients actually interact.

The problem isn’t lack of process, it’s lack of systems thinking. Someone, somewhere, decided that tracking pixel pings = email delivery. That decision got encoded into a system, which now automatically generates letters, which customer service agents are forced to defend. The loop is closed: the machine generates its own truth, and humans serve the machine.

The Enterprise Inertia Behind the Curtain

This failure mode is everywhere in enterprise IT. The Reddit discussion about Microsoft’s Outlook POP bug fix reveals the same pattern: who uses POP in 2026? Enterprises that built systems in 1998 and never updated them. The protocol is outdated, insecure, and unsuited for modern email, but it’s still running because “it works” (until it doesn’t).

The same inertia keeps tracking pixels in bank emails. Some marketing team demanded engagement metrics. Some vendor sold them an “email analytics platform.” Some developer implemented the pixel. Some compliance team signed off because “it’s just analytics.” No one connected the dots to see that they were building a surveillance system that would eventually eat its own tail.

This is how fragility becomes structural. Each layer of the stack makes locally reasonable decisions, but the global outcome is absurd. A bank that can’t tell if you got your email. A customer service agent who must insist you change your correct email address. A security team that approves HTTP tracking pixels.

What Actually Works: Protocol Literacy Over Surveillance

If HSBC needed to verify email deliverability, they had proper tools:

-

SMTP bounce codes. If an email actually bounces, the mail server returns a machine-readable code. This is how email has worked since 1982.

-

Double opt-in with authentication. Send a verification link that requires login. This confirms receipt and validates the user.

-

Read receipts (with consent). RFC 8098 defines a standard for read receipts that requires recipient approval. It’s built into email protocols and respects user autonomy.

-

Plain old customer communication. If you suspect deliverability issues, ask the customer: “Are you getting our emails?” Revolutionary.

Instead, HSBC chose surveillance because surveillance is scalable. Asking humans costs money. Pixels are cheap. The problem is that cheap surveillance produces expensive failures, like mailing letters to thousands of customers who are already reading their emails.

This reflects a broader overreliance on legacy tooling in enterprise systems. Organizations optimize for operational convenience at the expense of architectural correctness, then wonder why their systems behave unpredictably.

The Takeaway: Architecture Is About Intent

The HSBC email fiasco matters because it’s a canary in the coal mine. If a bank with $2.9 trillion in assets and 40 million customers can’t get email right, what else is broken? How many other systems conflate tracking with functionality? How many “AI-driven insights” are just garbage data from misconfigured pixels? How many customer service scripts enforce lies encoded in legacy code?

Enterprise architecture fails not from lack of frameworks, but from lack of protocol literacy and abdication of systems thinking. When you treat email as a surveillance channel rather than a communication protocol, you get letters telling customers to fix what isn’t broken.

The fix isn’t more process. It’s better engineers with the authority to ask: “What problem are we actually solving?” and “Why are we measuring this?” Until then, we’ll keep getting letters in the mail about our perfectly functional email, reminders that in the enterprise, the map has become the territory, and the map was drawn by someone who thinks a tracking pixel is the same as a protocol handshake.