Airflow’s Containerization Doctrine: Why Teams Are Quietly Ignoring the KubernetesOperator

A senior data engineer walks into a new company, ready to modernize their platform. They propose separating orchestration from pipelines using KubernetesOperator instead of PythonOperator. The response? Colleagues look at them like they suggested rewriting everything in COBOL. This isn’t a hypothetical, it’s a real scenario from a recent Reddit discussion that scored 37 upvotes and sparked 19 comments worth of architectural soul-searching.

The controversy cuts to the heart of a growing disconnect: Airflow’s architectural best practices are drifting further from what teams actually ship to production.

The Best Practices Doctrine vs. The Production Reality

The official guidance from Airflow’s ecosystem champions is clear, containerize your workloads. Astronomer’s recent ebook on scaling best practices pushes containerized execution as a cornerstone of production-ready architecture. The logic is sound: isolate dependencies, enable independent scaling, and treat tasks as ephemeral units of work. In theory, KubernetesOperator should be the default for any serious deployment.

Yet the numbers tell a different story. An overwhelming majority of production Airflow deployments remain stubbornly attached to PythonOperator. The Reddit thread reveals seasoned seniors questioning whether containerization is “actually common practice”, despite the architectural superiority claimed in vendor documentation. One commenter with significant influence noted that for lightweight scripts, PythonOperator is “probably fine”, a pragmatic concession that dominates real-world decision-making.

This isn’t just preference. It’s a fundamental divergence in how we conceptualize what Airflow should actually do.

The Operator Hierarchy: A Taxonomy of Execution

Understanding the gap requires parsing the subtle but critical distinctions in Airflow’s execution models:

- KubernetesOperator spins up a completely separate pod for each task, running containerized code with full isolation.

- KubernetesExecutor runs standard operators (including PythonOperator) but launches each task in its own pod. As one senior Airflow expert explained in the thread, this approach lets you “throw all the ‘don’t use airflow for compute’ advice out the window” while keeping the familiar operator interface.

- PythonOperator executes code directly in Airflow’s worker environment, sharing dependencies and resources across tasks.

Here’s where the debate gets spicy: the thread revealed that many teams using KubernetesExecutor with PythonOperator believe they’re following best practices. They’re containerizing execution without containerizing their code. It’s a middle ground that vendor documentation rarely acknowledges but production environments love.

The Anti-Pattern That Isn’t

The conversation exposed a critical definitional problem: what counts as “performing ETL” versus “orchestrating ETL”?

One engineer described using Airflow + BigQueryOperator to transform terabytes of data. Another senior practitioner immediately clarified: this isn’t an anti-pattern because “Airflow isn’t performing ETL in your examples. It’s orchestrating other tools to perform the ETL.” The compute happens in BigQuery, not Airflow’s workers.

The real anti-pattern? Running a PySpark job within a PythonOperator. When your worker node is crunching data instead of just triggering and monitoring, you’ve crossed the line. But that line is blurrier than best practices suggest.

A controversial take emerged: “Aren’t Airflow’s workers actually made to perform compute?” This comment, despite being downvoted, reflects a widespread misconception. Airflow’s workers are designed to execute orchestration logic, not data transformation. But the distinction gets lost when your “lightweight script” slowly grows into a 500-line data processing behemoth.

Why Teams Resist the Containerization Gospel

The Reddit discussion reveals five friction points that best practice guides gloss over:

- 1. The Complexity Tax

Containerizing every task means managing Dockerfiles, registries, image versions, and pod specifications. For a team maintaining 200 DAGs, that’s 200 containers to build, test, and secure. One engineer at a “super small company” noted they containerize everything because it’s “easier to maintain and debug”, but they have the luxury of greenfield development. Established teams face migration costs that can halt feature development for quarters. - 2. The Development Experience Gap

Writing a PythonOperator task takes minutes. Writing a KubernetesOperator task requires understanding pod specs, resource limits, volume mounts, and container lifecycles. When data scientists need to ship a quick model retraining pipeline, they reach for what they know. The cognitive load difference isn’t trivial, it’s the difference between shipping today versus next week. - 3. The “Good Enough” Performance Trap

Many workloads genuinely are lightweight. A PythonOperator that triggers an API call and waits isn’t straining the worker. The overhead of containerization feels like architectural theater when your task runs for 30 seconds once a day. Teams optimize for developer velocity, not theoretical resource isolation. - 4. The Legacy Inertia

As one commenter noted, “seasoned seniors” often drive the resistance. They’ve seen PythonOperator work reliably for years. The burden of proof lies on the new approach, not the proven one. This creates a catch-22: you can’t prove KubernetesOperator is better without production experience, but you can’t get production experience without proving it’s better. - 5. The Skill Matrix Reality

Container orchestration expertise remains concentrated. While challenges in on-the-job learning for data engineers adopting modern tools like Airflow continue to mount, expecting every data engineer to become a Kubernetes specialist is unrealistic. Teams choose architectures their current roster can support, not their ideal roster.

The Hidden Spectrum of Containerization

The binary choice between “pure KubernetesOperator” and “PythonOperator monolith” is false. The Reddit thread uncovered a pragmatic spectrum:

- Full Containerization (KubernetesOperator): Every task is a separate container. Best for complex dependencies, ML models with specific CUDA requirements, or tasks from different teams with conflicting library needs.

- Hybrid Approach (KubernetesExecutor + Selective Containerization): Most tasks use PythonOperator, but sensitive or complex DAGs get containerized. This “best of both worlds” approach emerged as the most common pattern among experienced teams. One senior engineer described containerizing “specific sensitive or complex DAGs due to special needs” while keeping the rest simple.

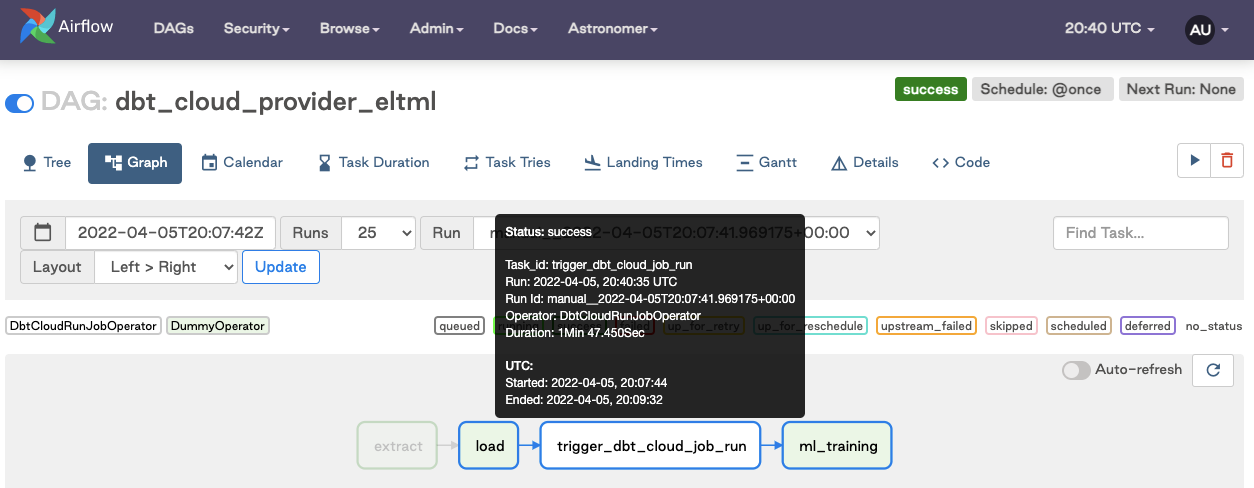

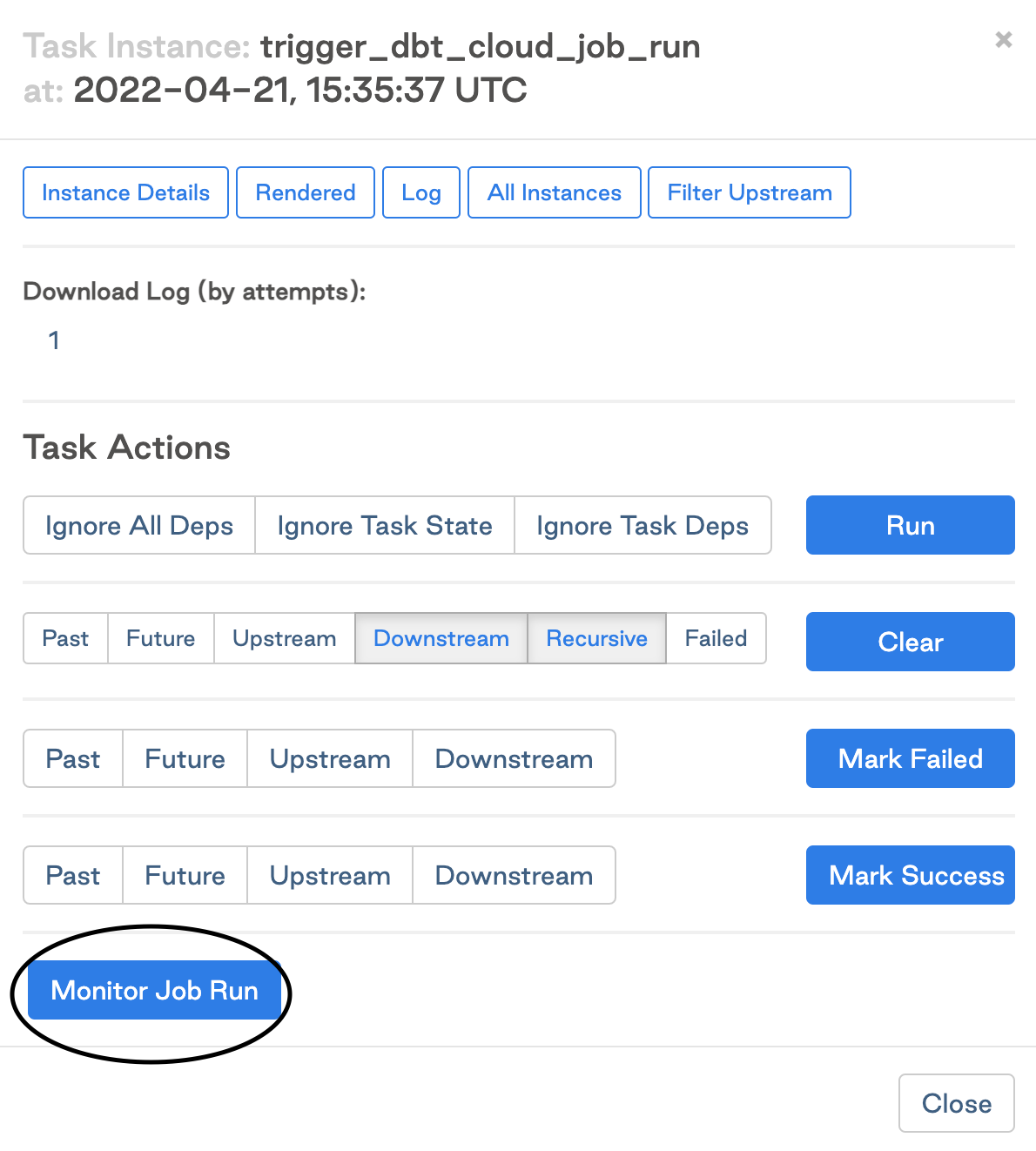

- The dbt Cloud Pattern: The dbt integration guide shows another path, using Airflow purely as a trigger mechanism. The heavy lifting happens in dbt Cloud’s infrastructure, not Airflow’s workers. This is decoupling through delegation rather than containerization.

The Cost of Container Purity

Pushing KubernetesOperator everywhere has hidden costs that vendor case studies (like OpenAI’s thousands of pipelines) don’t fully capture. Each containerized task adds:

- Cold start latency: Pod creation takes seconds to minutes

- Resource overhead: Kubernetes cluster costs for idle pods

- Observability complexity: Logs scattered across pod lifecycles

- Dependency management: Container supply chain security concerns

When to Actually Use KubernetesOperator

The data from the thread suggests three clear signals that containerization is worth the overhead:

- Resource heterogeneity: Tasks need different Python versions, conflicting C libraries, or GPU access

- Security isolation: Sensitive tasks can’t share an environment with general workloads

- Team autonomy: Different groups need to ship code on independent schedules without coordination

The Role Evolution Factor

This architectural debate mirrors broader evolving roles in data engineering, including how Airflow fits into changing ETL practices. As data engineers are asked to own more infrastructure decisions, the pressure to adopt “proper” containerization increases. But the same forces pushing for specialization also create skill gaps that make containerization harder to implement.

The irony? The engineers most equipped to implement KubernetesOperator (those with DevOps backgrounds) are often the ones advocating for simpler PythonOperator solutions, while data scientists pushing for containerization underestimate the operational complexity.

A Pragmatic Decision Framework

Instead of asking “Should we use KubernetesOperator?” teams should ask:

- What’s our median task runtime? Under 2 minutes, PythonOperator likely wins.

- How heterogeneous are our dependencies? More than 3 conflicting environments, consider selective containerization.

- What’s our team’s k8s expertise? If it requires hiring, factor that cost into the decision.

- How often do we ship new tasks? Daily shipping favors simplicity, weekly shipping can afford more ceremony.

The Verdict: Decoupling Is Happening, Just Not How Experts Predict

Teams are decoupling orchestration from pipelines, but they’re using KubernetesExecutor, not KubernetesOperator. They’re containerizing execution while keeping code in familiar Python functions. It’s a stealth decoupling that doesn’t require throwing out years of DAG development.

The spicy truth: the best practice is wrong for most teams, most of the time. Not because it’s technically incorrect, but because it solves problems most teams don’t have while creating problems they definitely do.

The real anti-pattern isn’t using PythonOperator, it’s letting architectural ideology override operational reality. The teams shipping reliable data pipelines aren’t the ones with the purest containerization strategy. They’re the ones that understand their workload, team capabilities, and business constraints.

Until the Airflow ecosystem acknowledges this pragmatic middle ground, senior engineers will keep getting side-eyed for suggesting the “right” architecture, and production DAGs will keep running on PythonOperator. And honestly? That’s probably fine.