The gospel of CUDA supremacy in AI inference has gone largely unchallenged for years. Nvidia’s proprietary stack has been the default choice for anyone serious about local LLM performance, with Vulkan often dismissed as a second-class citizen, a “cross-platform compromise” rather than a genuine contender. Recent benchmarking data suggests that assumption is overdue for a reckoning.

A developer running llama.cpp on an RTX 3080 10GB stumbled upon something that shouldn’t happen: certain quantized models were processing prompts significantly faster under Vulkan than CUDA. Not marginally. Not within measurement error. We’re talking 2.2× speedup in prompt processing for GLM4-9B Q6, and a staggering 4.4× improvement for Ministral3-14B Q4.

The Benchmarks That Broke the Narrative

The findings, posted to the LocalLLaMA subreddit, weren’t the result of synthetic microbenchmarks or cherry-picked conditions. They emerged from real-world testing across a model zoo, with most results confirming CUDA’s expected dominance, until they didn’t.

Token Generation Performance

| Model | CUDA (t/s) | Vulkan (t/s) | Diff (t/s) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERNIE4.5 21B-A3B Q6 | 25.8 | 13.2 | -12.7 | 0.51x |

| GLM4 9B Q6 | 25.4 | 44.0 | +18.6 | 1.73x |

| Ling-lite-i1 Q6 | 40.4 | 21.6 | -18.9 | 0.53x |

| Ministral3 14B 2512 Q4 | 36.1 | 57.1 | +21.0 | 1.58x |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B 2507 Q6 | 23.1 | 15.9 | -7.1 | 0.69x |

| Qwen3-8B Q6 | 23.7 | 25.8 | +2.1 | 1.09x |

Prompt Processing (The Real Shock)

| Model | CUDA (t/s) | Vulkan (t/s) | Diff (t/s) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLM4 9B Q6 | 34.0 | 75.6 | +41.6 | 2.22x |

| Ministral3 14B 2512 Q4 | 58.1 | 255.4 | +197.2 | 4.39x |

| Qwen3-8B Q6 | 30.3 | 46.0 | +15.8 | 1.52x |

The pattern is impossible to ignore: dense models with specific quantization levels are flipping the script. While MoE architectures like ERNIE4.5 and Qwen3-30B show expected CUDA superiority, the dense models, particularly those in the 8-14B parameter range with Q4-Q6 quantization, are hitting a fast path in Vulkan that CUDA completely misses.

Why This Is Happening (And Why It Matters)

The developer’s setup wasn’t exotic: a Ryzen 5, 32GB of DDR4, and llama.cpp built from latest source. The models were partially offloaded to GPU, a common configuration for 10GB VRAM cards. So what’s triggering this reversal?

One theory circulating in the thread points to memory management efficiency. When models are partially offloaded, the interaction between CPU RAM and GPU VRAM becomes critical. Vulkan’s explicit memory model might be handling this handoff more intelligently than CUDA’s abstraction layer in these specific scenarios. The fact that prompt processing (which is memory-bandwidth intensive) shows larger gains than token generation supports this hypothesis.

Another angle: kernel launch overhead. CUDA’s sophisticated scheduler introduces latency that Vulkan’s thinner abstraction avoids. For certain operation patterns, like those found in quantized dense models, this overhead becomes significant enough to erase CUDA’s compute advantage.

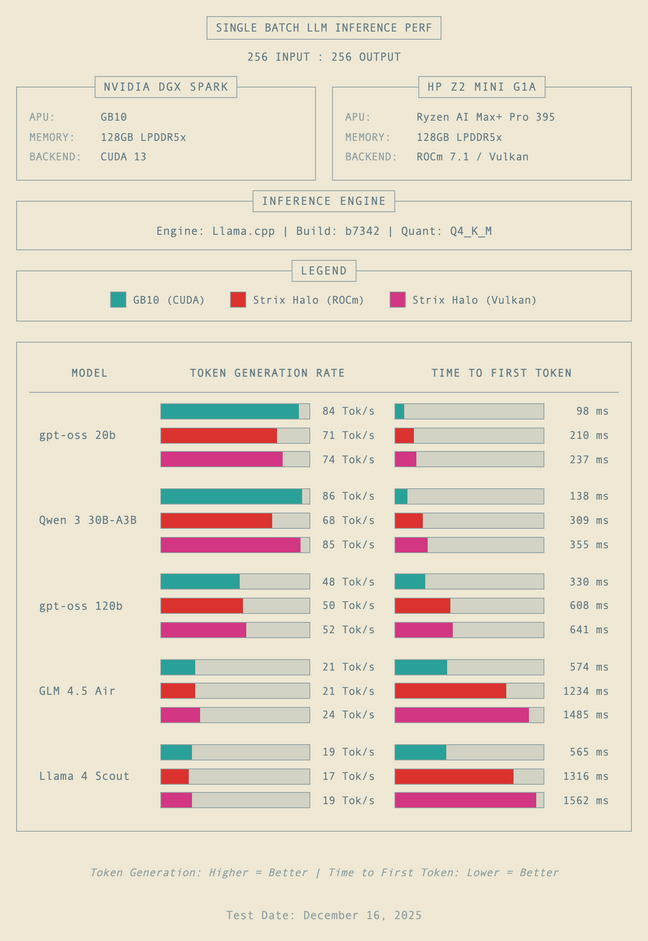

The Register’s recent testing of AMD’s Strix Halo against Nvidia’s DGX Spark provides broader context. Their benchmarks show Vulkan on AMD hardware trading blows with CUDA on Nvidia for token generation, though falling behind on time-to-first-token. This suggests the phenomenon isn’t isolated to a single Reddit user’s rig.

The CUDA Moat Isn’t Just Shallow, It’s Leaking

Nvidia’s software advantage has been framed as insurmountable, but these results puncture that narrative. Vulkan isn’t just a fallback for AMD users, it’s a legitimate optimization target that might be outperforming CUDA in untapped scenarios.

This matters because it shifts the optimization conversation. If Vulkan can deliver 2-4× speedups on consumer hardware, developers running llama.cpp and similar frameworks have a strong incentive to prioritize cross-platform backends. The “CUDA first, everything else second” development model starts looking less like pragmatism and more like leaving performance on the table.

A GitHub issue from December 2025 adds fuel to this fire. When the SYCL backend failed to offload prompt processing to GPU, Vulkan worked correctly out of the box. This reliability advantage, Vulkan doing what it’s supposed to while other backends stumble, could be more valuable than raw throughput in production environments.

Practical Implications for Local AI Users

If you’re running quantized models on consumer GPUs, you need to test both backends. The performance delta is too large to ignore. Here’s what the data suggests:

- For dense models (8-14B) with Q4-Q6 quantization: Start with Vulkan. The benchmarks show consistent wins, particularly for prompt processing.

- For MoE architectures: Stick with CUDA. The sparsity and routing complexity still favor Nvidia’s optimized kernels.

- For partial offloading scenarios: Vulkan’s memory handling might provide unexpected benefits. Test systematically with your specific model and context length.

- For time-to-first-token latency: CUDA maintains an edge, especially on longer prompts. If interactive responsiveness is critical, this could outweigh throughput gains.

The developer’s methodology is refreshingly honest: “deslopped jive code” with acknowledged imperfections. Yet the comparative results remain valid because they were generated using the same flawed methodology for both backends. This isn’t lab-perfect data, it’s real-world messy, which makes it more trustworthy for practitioners.

What This Means for the Ecosystem

The llama.cpp project has been aggressively optimizing its Vulkan backend for months. Release b7516 and subsequent builds include explicit Vulkan binaries alongside CUDA, signaling that maintainers see it as a first-class citizen. The performance gains aren’t accidental, they’re the result of deliberate engineering effort.

This creates a fascinating feedback loop: as Vulkan performance improves, more users adopt it, providing more benchmark data and bug reports, which drives further optimization. Meanwhile, CUDA’s dominance means it receives less critical scrutiny. The “good enough” syndrome could be masking inefficiencies that only surface when directly compared to a leaner competitor.

For AMD and Intel GPU owners, this is validation that their hardware isn’t inherently inferior, it’s just been underserved by software. For Nvidia users, it’s a wake-up call that their expensive cards might be underperforming due to framework choices, not hardware limitations.

The Bottom Line

The benchmarks don’t lie: Vulkan is beating CUDA for specific model configurations. This isn’t a theoretical possibility or a future promise. It’s happening right now on RTX 3080s and similar consumer cards running the latest llama.cpp builds.

The controversy isn’t that CUDA is bad, it’s that our assumptions about its universal superiority were premature. The inference stack is more nuanced than vendor marketing suggests, and cross-platform APIs are proving they can compete on performance, not just portability.

If you’re serious about local LLM performance, stop treating backend selection as a default setting. Benchmark your actual models, with your actual quantization, on your actual hardware. The 2.2× speedup hiding in your GPU won’t reveal itself otherwise.

The CUDA moat isn’t gone, but it’s definitely got some bridges across it. And right now, those bridges are carrying traffic faster than the castle walls.