The Persistent Nightmare of Datetime Handling in Data Engineering

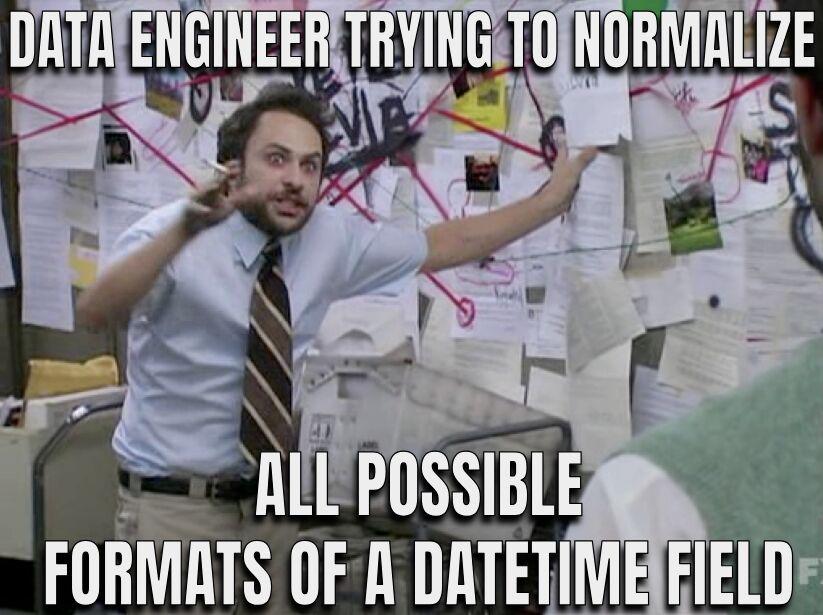

Despite decades of computing progress, datetime formatting remains a major pain point for data engineers, leading to bugs, pipeline breaks, and widespread frustration across systems and timezones.

The $47 Datetime That Broke 50 Tables

A recent migration saga illustrates the problem perfectly. A data engineer attempted to move 50+ tables from MySQL to Postgres using AWS Glue, a tool specifically designed for this purpose. The process should have been routine: connect, map, execute, grab coffee. Instead, it became a 48-hour descent into madness.

Table #37 failed. Then #41. Then #44. The error message was characteristically useless: ERROR: invalid input syntax for type timestamp. No row number. No column hint. Just a generic rejection from Postgres, which unlike MySQL’s permissive type coercion, refuses to tolerate datetime nonsense.

The culprit? A single row out of 10 million. One malformed timestamp in a sea of otherwise valid data. The created_at column contained this beautiful chaos:

2023-01-15 14:30:00 -- Standard MySQL datetime

01/15/2023 2:30 PM -- Someone's Excel export

January 15, 2013 -- Marketing team entry (note the year typo)

2023-1-15 -- Missing zero padding

15-Jan-23 -- European contractor

NULL -- Actually fine

"" -- Empty string (NOT fine)

Q1 2023 -- Why? Just... why?The cost of this detective work? $47 in AWS Glue DPU hours spent debugging, re-running, and eventually writing custom parsing logic. All because datetime handling remains an afterthought in modern data stacks.

PySpark’s Silent Betrayal

The natural next step was to clean the data with PySpark before loading it into Postgres. This is where things get dark.

The initial attempt used PySpark’s built-in timestamp casting:

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from pyspark.sql.types import TimestampType

spark = SparkSession.builder.getOrCreate()

df = spark.read.jdbc(url="jdbc:mysql://...", table="orders")

df = df.withColumn("created_at", F.col("created_at").cast(TimestampType()))Result: 30% of values became NULL. No errors. No warnings. Just silent data loss. PySpark’s type inference simply gave up on anything that wasn’t in a perfect format, pushing the problem downstream where it would explode later.

The next logical step was to_timestamp() with explicit format strings:

df = df.withColumn("created_at",

F.to_timestamp(F.col("created_at"), "yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss"))Result: 70% became NULL because they weren’t in that exact format. The function is rigid and unforgiving.

The engineer then tried chaining multiple formats using coalesce():

df = df.withColumn("created_at",

F.coalesce(

F.to_timestamp(F.col("created_at"), "yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss"),

F.to_timestamp(F.col("created_at"), "MM/dd/yyyy"),

F.to_timestamp(F.col("created_at"), "dd/MM/yyyy"),

F.to_timestamp(F.col("created_at"), "yyyy-MM-dd")

))This got them to 92% success with 8% NULLs, but "January 15, 2023" still failed. Adding 12 more formats made the query plan unreadable and pushed execution time to 45 minutes for 10 million rows. Even worse: there was no way to know which format matched which row, making debugging impossible.

The UDF Death Spiral

Desperate for a solution, the engineer wrote a Python UDF using dateutil.parser:

from pyspark.sql.functions import udf

from pyspark.sql.types import StringType

from datetime import datetime

import dateutil.parser

@udf(returnType=StringType())

def parse_datetime(value):

if not value:

return None

try:

return dateutil.parser.parse(value).strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S')

except:

return None

df = df.withColumn("created_at", parse_datetime(F.col("created_at")))Execution time: 6 hours.

Why? UDFs serialize every single row to Python, parse it, then serialize it back. The Spark UI showed the cluster was idle while the driver choked on Python overhead. This is the fundamental lie of "just write a UDF", it turns your distributed computing framework into an expensive single-threaded Python script.

A pandas UDF was slightly better:

from pyspark.sql.functions import pandas_udf

import pandas as pd

@pandas_udf(StringType())

def parse_datetime_pandas(s: pd.Series) -> pd.Series:

return pd.to_datetime(s, errors='coerce').dt.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S')Execution time: 2 hours. Still 8% NULLs, still no visibility into failures.

The final attempt before complete breakdown was multiple passes with different UDFs, each targeting a specific format. This required 600 lines of code across 8 UDFs, took 4 hours (multiple full table scans), and achieved 99.1% success. The engineer’s mental state, by their own admission, was "broken."

Timezones: The Invisible Minefield

While the original migration didn’t explicitly involve timezones, the broader community consensus is that timezone handling is where datetime problems graduate from annoying to catastrophic. One developer shared a horror story about a SaaS platform in a regulated industry that mandated all dates be stored in dd-month-yyyy format without timezone information. The resulting internationalization bugs were described as "unreal."

The standard advice, "just use Unix timestamps" or "always use ISO 8601", breaks down in practice because:

- Legacy systems don’t care about your standards. They export Excel dates as strings like "01/15/2023 2:30 PM" with no timezone indicator.

- Humans are the enemy. Marketing teams manually enter "January 15, 2023" into fields that get dumped into databases.

- Timezones are political. They change. Countries abolish daylight saving time without notice. Your static timezone offset table is already out of date.

As one developer noted, the real nightmare begins when you have to deal with "a little bit of TZ, a touch of LTZ, a sprinkle of NTZ… and then compare them all to DATE in the end."

The 2AM Abomination

At 2 AM, after 6 failed attempts, the engineer produced what they called the "nuclear option", a 200-line pandas UDF that tried everything:

from pyspark.sql.functions import pandas_udf

import pandas as pd

from dateutil import parser

import re

@pandas_udf(StringType())

def parse_datetime_nuclear_option(s: pd.Series) -> pd.Series:

def parse_single(value):

if pd.isna(value) or value == "":

return None

# Try pandas first (fast)

try:

return pd.to_datetime(value).strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S')

except:

pass

# Try dateutil (slow but flexible)

try:

return parser.parse(str(value), fuzzy=True).strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S')

except:

pass

# Try regex extraction for ISO

match = re.search(r'\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}', str(value))

if match:

return match.group(0) + ' 00:00:00'

# Try named months (40+ lines of mapping)

months = {'january': '01', 'jan': '01', 'february': '02', ...}

# Try quarter notation (20+ more lines)

if 'Q' in str(value):

# ... complex logic

return None

return s.apply(parse_single)Execution time: 8 hours. Success rate: 99.4%. Cost: $47 in AWS Glue DPU hours.

The remaining 0.6% included truly cursed data: "FY Q3 2023", "some time in january", and the masterpiece "2023-13-45" (month 13, day 45, someone apparently mashing the number row).

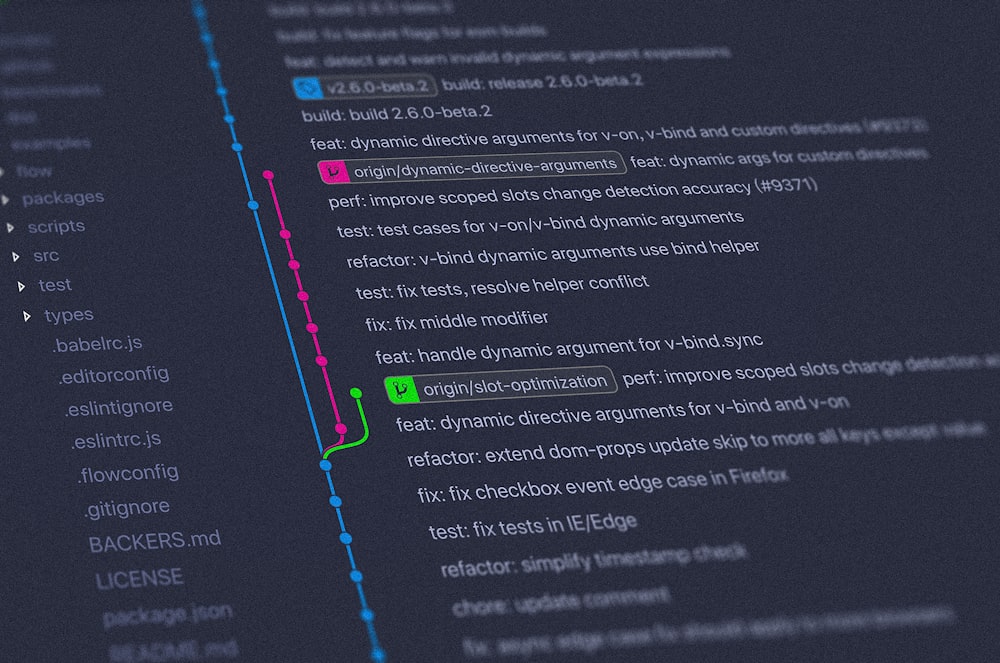

At 4 AM, with 12 more tables to fix, the engineer had a revelation: the problem wasn’t the parsing logic, it was the execution model.

The Native PySpark Awakening

The breakthrough came from abandoning UDFs entirely. The solution was to stay within PySpark’s native Column expressions, letting Spark’s Catalyst optimizer do its job:

from transformers.pyspark.datetimes import datetimes

df = df.withColumn("created_at", datetimes.standardize_iso(F.col("created_at")))Execution time: 3 minutes. Same 10 million rows. Same 50+ format variations. 3 minutes.

What looks like a function call is actually returning a PySpark Column expression, a massive coalesce() chain with regex extractions that Spark can optimize as a single execution plan:

F.coalesce(

F.to_timestamp(col, "yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss"),

F.to_timestamp(col, "yyyy-MM-dd'T'HH:mm:ss"),

F.to_timestamp(col, "MM/dd/yyyy HH:mm:ss"),

F.to_timestamp(col, "MM/dd/yyyy"),

# ... 50 more patterns

parse_named_month(col), # "January 15, 2023" → regex + reconstruction

parse_european(col), # "15/01/2023" → regex + reconstruction

)The key insight: UDFs serialize data to Python, native expressions stay in the JVM. Spark can optimize the entire chain, push down predicates, and distribute the work efficiently. The "magic" is just code you don’t have to write again.

The Broader Crisis

This isn’t just one engineer’s nightmare, it’s an industry-wide failure. The research shows datetime handling consistently ranks among the top pain points in data engineering forums, with developers calling it a "rite of passage" and comparing it to "circles of hell."

The problem persists because:

- Standards exist but aren’t enforced. ISO 8601 is a standard, Excel’s date format is reality.

- Tools prioritize convenience over correctness. MySQL’s loose typing gets you started quickly but creates technical debt that explodes during migration.

- Error messages are useless. "Invalid input syntax" doesn’t help you find the one bad row in 10 million.

- Performance vs. flexibility is a false choice. Engineers accept 6-hour UDF runtimes because they don’t know there’s a 3-minute alternative.

What Actually Works

The path forward requires three shifts:

First, enforce standards at ingestion. If a system exports dates as "January 15, 2023", push back. Add validation at the source. Store everything as ISO 8601 strings with explicit timezones in your raw data lake.

Second, never reach for a UDF as the first solution. PySpark’s native functions are more powerful than they appear. A chain of coalesce() and to_timestamp() with 50 patterns is ugly but runs in minutes, not hours.

Third, treat datetime parsing as a first-class problem. The DataCompose approach, building a library of tested, composable primitives, means you solve the problem once and reuse it. Your custom 200-line UDF is a liability, a community-tested primitive is an asset.

The 0.6% of truly cursed data? Let it fail. Use is_valid_date to flag garbage and deal with it manually. Some data is so malformed it shouldn’t be silently coerced, it should be fixed at the source or rejected entirely.

The Takeaway

After decades of computing progress, datetime handling remains a nightmare because we’ve been solving it at the wrong layer. We’ve accepted silent NULLs, 6-hour UDFs, and useless error messages as normal. They’re not.

The next time your pipeline fails with invalid input syntax for type timestamp, remember: the problem isn’t your data, it’s your approach. Stop serializing to Python. Stop writing one-off UDFs. Start using native expressions and enforce standards early.

Your future self, debugging a pipeline at 4 AM, will thank you.