Your RDS bill is bleeding you dry, and those immutable invoice records are the wound. The standard playbook says: move cold data to S3, front it with Athena or Redshift Spectrum, and call it a day.

“Is querying JSON from S3 acceptable for an API handling 3,500 requests per second?”

The reflexive answer is no. The honest answer? It depends on whether you’re optimizing for architecture purity or actual cost savings.

The Cold Data Dilemma: When Immutable Means Inaccessible

The scenario is painfully familiar. A fintech company runs PostgreSQL for invoices, but closed records, immutable, read-only, yet still queryable, are eating 70% of storage costs. Hot data (open invoices) sits at 6,000 requests per second. Cold data (closed invoices) chugs along at 3,500 rps. The proposed solution: AWS Glue dumps JSON to S3, API Gateway routes requests accordingly, and the CFO gets to buy a new Tesla with the savings.

But here’s where the architecture gods start screaming. S3 isn’t a database. It’s object storage with eventual consistency, no indexing, and query patterns that feel like using a forklift to find a contact lens. The thread quickly devolved into the usual suggestions: DuckDB on Delta Lake, Athena for serverless queries, maybe even OpenSearch with UltraWarm tiering.

The critical insight came from a commenter who cut through the noise: “You skipped the use cases with ‘reading the cold data’ which is key.”

That comment is worth its weight in provisioned IOPS.

The S3-First Approach: When JSON Is Actually Enough

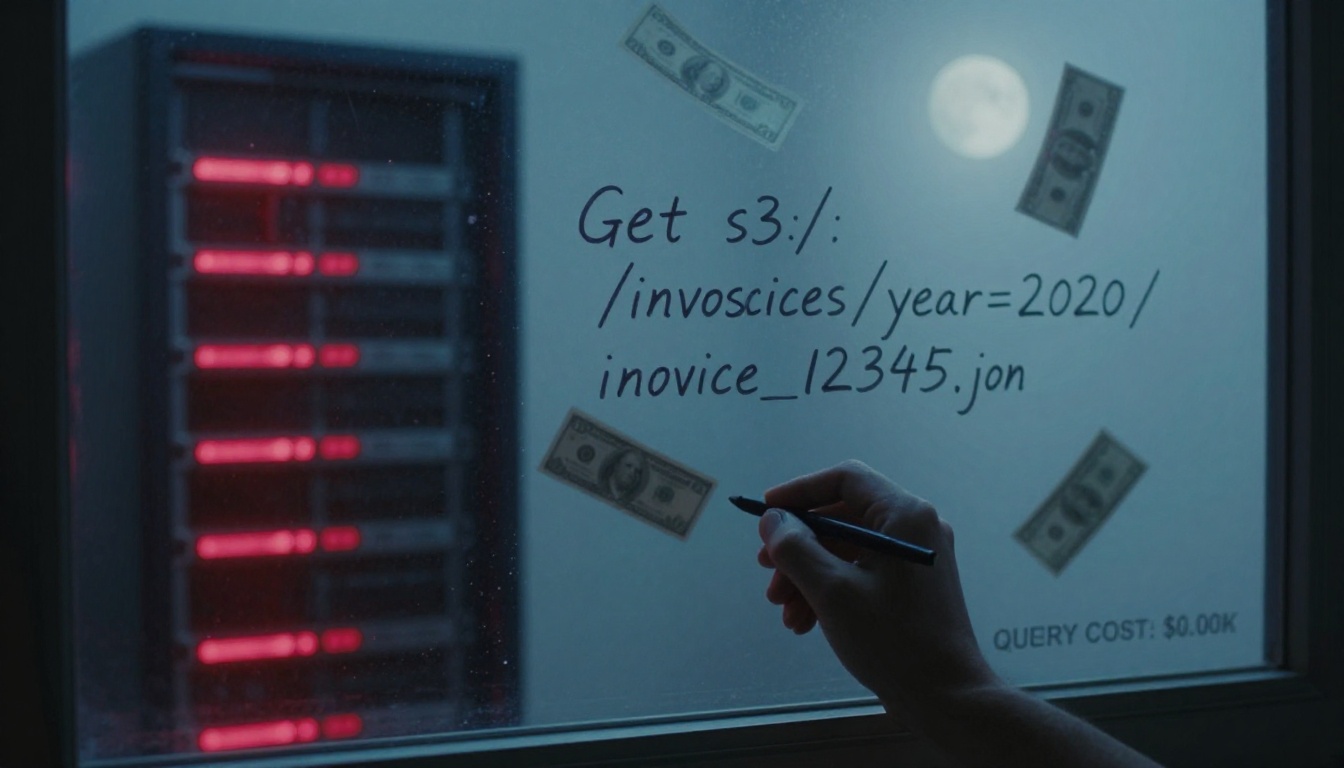

Let’s do the napkin math that most teams avoid. S3 supports 5,500 requests per second per partition prefix. With proper key partitioning (e.g., s3://bucket/invoices/year/month/day/{invoice_id}.json), you can theoretically handle 3,500 rps without breaking a sweat. The cost? $0.0004 per 1,000 requests. That’s $1.68 per day for your cold data API layer.

Compare that to Athena: $5 per TB scanned. If each query scans even 10MB of data, you’re looking at $0.00005 per query. At 3,500 rps, that’s $15,120 per day. The math isn’t just different, it’s existential.

The catch, and it’s a big one, is access patterns. If your API needs to:

- Retrieve a single invoice by ID: S3 GET is perfect

- Filter invoices by customer, date range, and status: You’re building a database on top of S3

- Perform aggregations across customer segments: Abandon hope

This is where the audit logs table pattern becomes instructive. Append-only data in a primary database creates a scaling time bomb. But once that data is truly cold, never updated, rarely scanned, S3’s limitations become features. You’re trading query flexibility for cost savings that scale linearly with volume.

The Analytical Database Trap: Why Athena Isn’t Your API Friend

The poster’s instinct about Athena was correct, but for the wrong reasons. They worried about TPS. The real problem is cost unpredictability and latency.

Athena is stateless and serverless, which feels perfect for APIs until you see the bill. Each query scans entire partitions. There’s no query cache across invocations. And that 3,500 rps? Athena would treat each as an independent query, potentially scanning the same data 3,500 times per second.

But here’s the spicy take: The problem isn’t Athena. The problem is using analytical databases for transactional access patterns.

Analytical databases, Redshift, Snowflake, even OpenSearch’s cold storage tier, are designed for scanning, not serving. They excel when you can decouple compute from storage and batch-process insights. They fail when you need predictable sub-100ms latency for random access.

OpenSearch’s cold storage documentation reveals the underlying architecture: “you can query the attached cold data with a similar interactive experience and performance as your warm data.” The keyword is interactive, not programmatic. It’s for dashboards, not APIs.

The Use Case Trap: Where Fintech Requirements Actually Help

Financial data has unique constraints that simplify this decision. Let’s revisit the immutable invoice scenario with proper fintech requirements:

- Auditability: Every invoice must be retrievable, unmodified, forever

- Time-travel queries: “What was invoice #12345 on December 1st?” (Spoiler: it hasn’t changed)

- PII separation: Customer data lives elsewhere, linked by anonymized IDs

- No aggregations: Regulatory reports run separately, APIs serve single records

These constraints point toward a document-store pattern, not a relational one. The Ispirer blog’s financial data architecture guide emphasizes the immutable ledger pattern: store every transaction as a permanent record, calculate balances on read.

For cold invoices, this means your API queries are essentially GET s3://bucket/invoices/{id}.json. That’s it. No joins, no filters, no aggregations. The “query” is a primary key lookup, and S3 is shockingly good at those.

The Hybrid Pattern: S3 as the Source of Truth

The thread’s most valuable suggestion wasn’t DuckDB or Athena, it was the implicit recognition that cold data needs a different abstraction layer.

- Hot data: PostgreSQL with partial indexes on open invoices only

- Cold migration: AWS Glue writes invoices to S3 as Parquet (not JSON) on closure

- API routing: Application layer checks a metadata cache (DynamoDB) for invoice status

- Cold reads: Direct S3 GET for cold invoices, with CloudFront for caching

- Emergency fallback: Athena for ad-hoc queries, throttled to prevent cost explosions

The key is the metadata cache. It tells you where the data lives without scanning S3. A single DynamoDB query (sub-10ms) routes to either PostgreSQL or S3. This avoids the DynamoDB $21k burn scenario by using it only for routing, not data storage.

Parquet instead of JSON cuts storage costs by 70% and enables zero-copy reads for analytical workloads. The format matters less for API performance than for downstream cost optimization.

The Real Cost: Architecture Complexity vs. Infrastructure Savings

The poster’s company wanted to “reduce database storage costs while improving performance.” These are conflicting goals. Moving data to S3 improves the cost metric but introduces latency variance. Using Athena improves query flexibility but destroys the cost metric.

The actual solution requires accepting that cold data queries will be slower. Not tragically slower, 50ms to S3 vs. 5ms to RDS, but measurably slower. If your API SLA requires sub-20ms p99, S3 is off the table. If you can tolerate 100ms for historical invoices, it’s a no-brainer.

This is the integrity vs. performance tradeoff that database designers have faced for decades. In fintech, we’ve historically optimized for integrity at all costs. But with truly immutable data, integrity is guaranteed by the storage format (append-only Parquet) and cryptographic checksums, not by database constraints.

The Tiered Storage Reality Check

Let’s kill a myth: Tiered storage isn’t about hot vs. cold. It’s about access pattern predictability.

AWS’s own guidance for core banking systems on AWS shows the real architecture: real-time transactions hit QLDB (200ms SLA), batch processing uses FSx for Lustre, and archival lives in S3. They don’t query S3 from APIs because they don’t need to, the access patterns are separated by business function.

The fintech invoice scenario is different. The API is unified. This forces a choice:

- Predictable lookups: S3 + metadata cache

- Unpredictable queries: OpenSearch UltraWarm or similar

- Analytical scans: Athena (but not from the API)

The CDC vs. microbatching debate is relevant here. Cold data migration is inherently batch-oriented. Trying to treat it as a real-time synchronization problem leads to overbuilt solutions. Glue jobs running hourly to move closed invoices are fine, customers don’t expect real-time access to last month’s bill.

The Decision Framework: A Flowchart for the Cynical

Cut this out and tape it to your monitor:

Is your cold data accessed by PRIMARY KEY only?

├─ YES → S3 + metadata cache (cost: $0.02/TB/month)

├─ NO → Do you need sub-100ms latency?

├─ YES → Keep it in RDS, pay for storage (cost: $0.115/GB/month)

└─ NO → Do you scan >1TB/day?

├─ YES → OpenSearch UltraWarm (cost: $0.024/GB/month)

└─ NO → Athena + partition pruning (cost: unpredictable)

The controversial truth: Most fintech “cold data” isn’t cold enough to justify the architectural complexity.

If you’re querying it 3,500 times per second, it’s not cold, it’s lukewarm. The real cost savings come from moving truly cold data (accessed <1/day) to Glacier, not from optimizing your API’s storage backend.

You’re Probably Overthinking It

The thread’s highest-scored comment asked for use cases. The poster never answered. That’s the real story here, we architect solutions without defining the problem.

If your API needs to serve random invoice lookups at high throughput, S3 with proper partitioning works. It’s not elegant. It won’t win conference talks. But it will save you $50k/month in RDS storage costs while delivering 99.9% availability.

If you need complex queries, aggregations, or sub-10ms latency, keep the data in a database. Accept that storage costs are part of your COGS. Don’t build a Rube Goldberg machine to save a few thousand dollars while adding three new failure modes.

The rise of tiered storage isn’t about making S3 queryable. It’s about admitting that not all data deserves database capabilities. Most of your historical records are digital landfill, necessary for compliance, irrelevant for operations.

Query them from S3. Sleep well. Let the architecture purists scream into the void.

The Real Talk Checklist

Before you migrate a single byte, answer these:

- What’s the actual query pattern? (Primary key vs. scan)

- What’s the latency SLA? (20ms vs. 200ms changes everything)

- What’s the cost baseline? (Calculate current spend per query)

- What’s the query shape? (If you need JOINs, stop reading and keep RDS)

- What’s the fallback plan? (When S3 has a bad day, what breaks?)

If you can’t answer #1 with certainty, you don’t have a cold storage problem. You have a product requirements problem. And no amount of DuckDB wizardry will fix that.