OpenClaw’s Viral Rocket Ship: Engineering Marvel or Marketing Mirage?

When OpenAI announced it had hired Peter Steinberger, creator of the viral AI agent framework OpenClaw, the press release hit every Silicon Valley sweet spot: open-source evangelism, agentic AI hype, and a founder who “turned down the chance to build his own company.” The tech press rushed to call it Sam Altman’s most strategic talent grab of 2026.

But beneath the celebratory headlines, a more cynical narrative was taking shape in the AI community’s trenches. Developers who had watched OpenClaw’s GitHub star count skyrocket overnight weren’t celebrating, they were squinting. Hard.

The suspicion wasn’t about OpenClaw’s technical premise. The idea of a locally-running AI agent that can control your computer, manage APIs, and automate tasks has been discussed since GPT-3.5. The red flags were about something more fundamental: whether anyone was actually using this thing.

The Star Chart That Launched a Thousand Forks

The controversy crystallized around a single graph from star-history.com showing OpenClaw’s GitHub stars exploding from zero to over 200,000 in a single month. For context, ComfyUI, one of the most popular AI tooling projects with genuine organic adoption, showed a gradual, years-long climb. OpenClaw’s line went vertical.

“This graph is obviously fake”, posted one developer on r/LocalLLaMA, voicing what many were thinking. The sentiment resonated: the post scored 621 upvotes and sparked 176 comments from engineers who couldn’t find a single colleague, online or in-person, actually running OpenClaw in production.

The Guerrilla Marketing Playbook

What transformed suspicion into conviction were the allegations about Peter Steinberger’s marketing tactics. Multiple community members pointed to a pattern: manufactured news presented as breakthroughs. The claim that OpenClaw “started its own language.” The assertion of 500,000 agents connecting in the first week. The precise 200,000 GitHub stars in 30 days.

These weren’t organic community metrics, they were press release numbers, and they were appearing in coordinated media blasts before the developer community had even heard of the project.

One developer put it bluntly: “Most OpenClaw conversations in the news were fake, made by him or marketing people.” The pattern felt familiar to anyone who survived the crypto boom: a fierce competition for eyes and attention where the most aggressive liar wins.

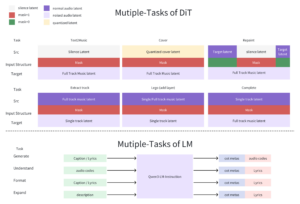

This exposed marketing hype in AI agent platforms parallels suspicions around OpenClaw’s virality, a pattern we’ve seen before in projects that promise autonomous AI societies but deliver puppet shows.

Why OpenAI Fell For It (Or Didn’t)

The OpenAI acquisition, or “hiring”, depending on which press release you read, created more confusion than clarity. Steinberger would join OpenAI’s Codex team while OpenAI “sponsored” OpenClaw as a foundation. The deal size was never disclosed, but Steinberger himself floated a $10 billion valuation on Lex Fridman’s podcast, a number so absurd it became evidence of the grift.

So why would OpenAI, a company supposedly in a “code red” after losing users to competitors, buy into obvious hype?

-

The Bot Farm Theory: OpenClaw’s architecture made it a perfect starter kit for AI bot farms. OpenAI might be acquiring the infrastructure to study or control the bot ecosystem.

-

The Marketing Coup Theory: The acquisition itself generates headlines and positions OpenAI as the shepherd of open-source agentic AI, regardless of the project’s actual merit.

-

The Talent Theory: Steinberger, despite the controversy, successfully executed one of the most effective marketing campaigns in AI history. That skill has value, even if the product was vapor.

The third theory gained traction when developers noted Steinberger’s track record: he built PSPDFKit, a PDF software company with a successful exit. He knows how to create and sell developer tools. OpenAI might be betting that his marketing genius, properly directed, could be valuable.

The Forks Tell The Real Story

Perhaps the most damning evidence against OpenClaw’s organic success is the ecosystem that emerged around it. Not a thriving community of contributors, but a graveyard of forks: ironclaw, zeroclaw, tinyclaw, nanoclaw, picoclaw.

When a project generates this many variations early in its lifecycle, it typically signals that the core project failed to address real needs. Developers aren’t building on top, they’re building alternatives from scratch. The fragmentation means improvements get scattered across repositories, none achieving critical mass.

As one developer noted: “The few who have checked it out think it’s garbage. Was just another weekend whim. Star it and never go back.”

This phenomenon mirrors volume-driven AI content generation as a tactic for manufactured online presence, where quantity is deployed to create an illusion of momentum.

Security Nightmare, Utility Mirage

Beyond the hype manipulation, OpenClaw’s technical implementation raised serious red flags. The agent required full system access to be useful, making it a “security nightmare by design.” Prompt injection attacks remain unsolved, meaning any text the agent processes could potentially hijack its operations.

Yet defenders argued the convenience justified the risk. “It connects APIs and MCP servers”, they said. “That’s valuable.”

Critics countered: this was a composition of existing tools, not innovation. As one engineer put it: “Complexity arises from composition. Performance comes from execution. Apple didn’t invent the smartphone components, but they executed flawlessly. OpenClaw is no iPhone, it’s a buggy compilation that barely works.”

The security concerns tie directly to security and authenticity risks in AI agents highlight concerns about genuine autonomy, where the gap between marketing promise and technical reality creates dangerous vulnerabilities.

The China Connection and Competitive Pressure

OpenClaw’s narrative took an interesting turn when reports emerged of its popularity in China, with Baidu planning to integrate it into smartphone apps. This international angle added legitimacy to its growth story.

But it also highlighted the AI arms race dynamics at play. While China’s competitive AI agent advancements contrast with OpenClaw’s unverified rise, showing genuine strategic competition, OpenClaw’s story felt more like theater than substance.

The timing was perfect: AI labs are desperate for agentic AI breakthroughs. The arms race over model benchmarks is giving way to a messier, more practical battle, getting agents to actually do useful things across real apps and workflows. OpenClaw positioned itself as the answer, but delivered a demo.

The Crypto Parallel Nobody Wants to Admit

The most uncomfortable comparison came from developers who lived through the crypto boom. “AI has become what crypto was a couple of years ago”, one wrote. “A fierce competition for eyes and attention, and the one that lies more, wins.”

The pattern is unmistakable:

– Manufactured scarcity (“Mac Minis are selling out to run OpenClaw!”)

– Unverifiable usage claims

– Influencer coordination

– Pump-and-dump dynamics (though with attention instead of tokens)

– A community that feels manipulated

Even the name evolution, from Clawdbot to Moltbot to OpenClaw, felt like brand optimization for virality rather than product development.

What This Means for AI Trust

OpenClaw’s story, whether a deliberate scam or just aggressively optimistic marketing, reveals a crisis of authenticity in AI development. When GitHub stars can be bought, when Twitter buzz can be manufactured, when even OpenAI can’t distinguish real momentum from marketing, the entire ecosystem suffers.

The tragedy is that the underlying idea, local, controllable AI agents, is genuinely compelling. Developers want this tool. But the manufactured hype creates a boy-who-cried-wolf scenario. The next project with organic growth will be met with suspicion, thanks to OpenClaw’s playbook.

For the AI community, the lesson is clear: demand receipts. Not GitHub stars, not Twitter impressions, but real user stories, production deployments, and technical depth. The era of trusting momentum is over.

The Verdict

Did OpenClaw fake its way to an OpenAI acquisition? The evidence suggests at minimum a highly manipulated growth story. The star history, the coordinated media blitz, the unverifiable usage claims, and the technical sloppiness all point to marketing over merit.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: it worked. Steinberger now leads personal agent development at OpenAI. OpenClaw remains in the news. And the playbook, whether deliberate deception or just Silicon Valley optimism run amok, will be studied and likely copied.

The real question isn’t whether OpenClaw’s rise was manufactured. It’s whether we, as a community, will keep falling for it. As one developer warned: “If they lied to start, they will continue lying.”

In an industry racing toward AGI, maybe we should expect our agents to be a little too good at gaming human attention. After all, that’s precisely what they’re designed to do.

The Takeaway: Next time you see a project go from zero to viral in 30 days, ask yourself: do I know anyone actually using this? If the answer is no, you might be watching a marketing campaign, not a movement. Demand technical depth, security audits, and real user stories before starring that repo. The future of AI depends on our ability to distinguish genuine innovation from sophisticated vaporware.