The AI world woke up to a coordinated assault on the agentic frontier. Within hours of each other, Zhipu AI dropped GLM-5 and MiniMax unleashed M2.5, both claiming supremacy in the race to build AI that doesn’t just chat, but does. This isn’t incremental improvement, it’s a declaration of war on the entire paradigm of language models as conversational toys. The battlefield? Long-horizon task completion. The weapons? Two radically different philosophies about what makes agents actually work.

The End of the Chatbot Era

For years, the AI race has been measured in benchmark scores and context window sizes, a pissing contest over who could generate the most coherent paragraph. GLM-5 and MiniMax M2.5 change the rules entirely. These models are engineered not for banter, but for completion. They target complex systems engineering, workflow automation, and the kind of autonomous task execution that Silicon Valley has been promising but failing to deliver.

The timing is deliberate. Chinese New Year week saw a cascade of releases: Seedance 2.0, Seedream 5.0, Qwen-image 2.0, and now these two agentic heavyweights. It’s a flex, a demonstration that China’s AI ecosystem has moved beyond catch-up mode into coordinated, strategic offense. The message is clear: while Western labs debate AGI timelines, Chinese teams are shipping production-grade agents that can run a vending machine business for a year or debug a CLI tool without human hand-holding.

GLM-5: The Reasoning Leviathan

Zhipu AI didn’t just scale up, they scaled smart. GLM-5 jumps from 355 billion parameters (32B active) to 744B parameters (40B active), trained on 28.5 trillion tokens, up from 23T in GLM-4.5. But raw size is the least interesting part. The model integrates DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA), cutting deployment costs while preserving the 200K context window that makes long-horizon planning possible.

The training methodology reveals deeper ambition. While DeepSeek proved FP8 training viable, GLM-5 stuck with FP16. The reason isn’t technical conservatism, it’s hardware reality. Rumors suggest domestic Chinese AI chips handle FP16 more reliably, a subtle nod to the geopolitical undertones of this release. The choice represents a strategic decoupling: optimize for self-sufficiency, not just efficiency.

GLM-5’s post-training infrastructure, dubbed “slime“, introduces asynchronous RL to bridge the gap between competence and excellence. This isn’t fine-tuning, it’s a continuous improvement loop that lets the model iterate on its own reasoning patterns without the catastrophic forgetting that plagues traditional RLHF.

Benchmark Reality: Where GLM-5 Dominates

The numbers tell a story of architectural depth over brute force:

| Benchmark | GLM-5 | GLM-4.7 | DeepSeek-V3.2 | Claude Opus 4.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

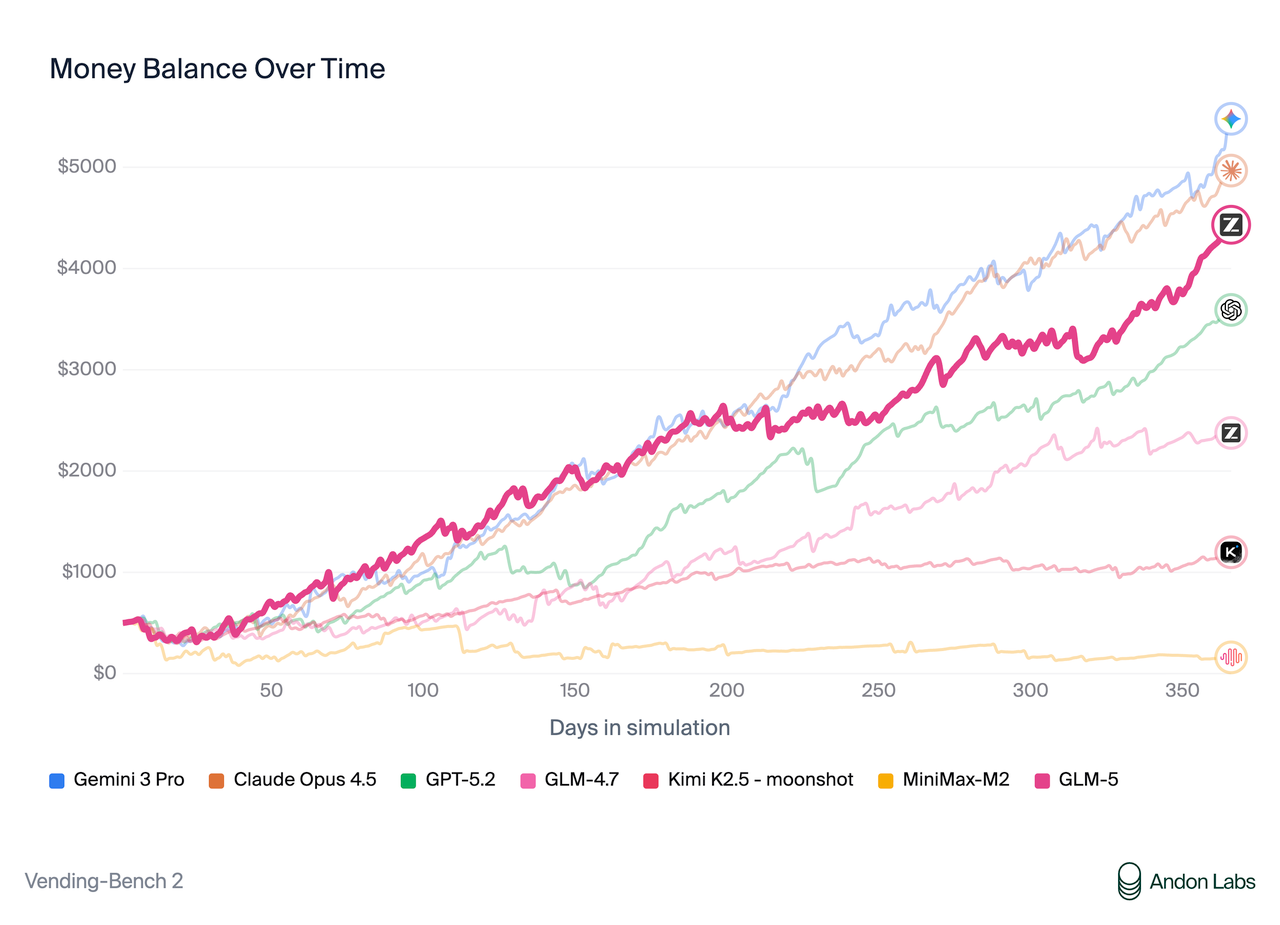

| Vending Bench 2 | $4,432 | $2,376 | $1,034 | $4,967 |

| SWE-bench Verified | 77.8% | 73.8% | 73.1% | 80.9% |

| Terminal-Bench 2.0 | 56.2/60.7 | 41.0 | 39.3 | 59.3 |

| Humanity’s Last Exam | 30.5 | 24.8 | 25.1 | 28.4 |

Vending Bench 2 is particularly revealing. The task, running a simulated vending machine business for a year, requires planning, resource management, and adaptation. GLM-5’s $4,432 final balance nearly matches Claude Opus 4.5’s $4,967 and crushes its predecessor. This isn’t trivia, it’s operational competence.

The model also turns text directly into deliverable documents, PDFs, Word files, Excel sheets. A sponsorship proposal for a high school football team, an NVIDIA equity research report, a Google earnings review. This “Office mode” represents a fundamental shift: from generating text to producing work product.

MiniMax M2.5: The Execution Engine

While GLM-5 obsesses over reasoning depth, MiniMax M2.5 optimizes for getting things done. The architecture emphasizes sparse activation and task decomposition, trading architectural purity for execution efficiency. Based on M2.1’s pattern (230B total, 10B active), M2.5 likely maintains the same efficiency-first design but enhances agentic coordination.

The pricing tells the real story. MiniMax M2.1 costs $0.30 per million input tokens and $1.20 output, half GLM-5’s $0.80/$2.56 rate. For agent loops that consume millions of tokens daily, that 60% cost reduction compounds into operational viability. One developer reported cutting their agent bill by 80% switching from GLM to MiniMax, with cached context runs costing pennies.

The “Finisher” Reputation

Where GLM-5 generates beautiful architecture documents, MiniMax M2.1 ships code. Developer reports consistently describe a model that completes tasks. In one Kilo Code test, it built a full CLI task runner with 20 features, hit a bug with Commander.js parsing, tested the library inline using Node to diagnose the issue, then fixed its own code, running 14 minutes without human intervention.

This self-debugging capability explains why MiniMax excels at long-running workflows. GLM-5 might generate cleaner abstractions, but MiniMax reaches a valid end state with lower variance. It’s the difference between a brilliant architect who never stops drawing blueprints and a competent contractor who actually builds the house.

Divergent Strategies, Same Destination

The models embody opposing philosophies:

| Dimension | GLM-5 | MiniMax M2.x |

|---|---|---|

| Instruction Adherence | 7/10 (expands scope) | 9/10 (stays bounded) |

| Planning Depth | 9/10 (system-level reasoning) | 6/10 (tactical execution) |

| Execution Efficiency | 6/10 (slower, expensive) | 9/10 (fast, cheap) |

| Code Quality | 9/10 (clean abstractions) | 7/10 (simple, direct) |

| Documentation | 9/10 (rich READMEs) | 3/10 (minimal docs) |

GLM-5 behaves like a research partner who wants to explore every design pattern before committing. MiniMax acts like a senior engineer who knows the deadline is Friday and ships working code on Thursday. Neither is wrong, they’re optimized for different definitions of success.

The Security Time Bomb

This agentic shift introduces a critical vulnerability that neither model fully addresses. As security researchers have warned, autonomous agents with broad tool access are susceptible to prompt injection attacks. An agent reading its own email or browsing social media could encounter hidden instructions that trick it into leaking data or draining wallets.

Chinese tech giants are racing to integrate these models into cloud platforms, Tencent, Alibaba, and ByteDance have all added OpenClaw support despite documented risks. The enthusiasm is understandable: the productivity gains are real. But deploying agents with file system access and API credentials in shared environments is like giving a toddler the keys to your car and hoping they read the owner’s manual first.

The Economic Architecture of Agentic AI

The pricing strategies reveal deeper market positioning. GLM-5 targets enterprises willing to pay premium rates for reasoning transparency and document generation. MiniMax courts high-volume users building agent swarms where every cent per token matters.

This bifurcation mirrors China’s broader AI economic strategy. While Moonshot AI secures $500M Series C funding to push API-first infrastructure, and Alibaba bets billions on scaling laws, the ecosystem is segmenting into premium reasoning and commodity execution layers.

The real innovation isn’t in the models themselves, it’s in the orchestration. Developers are already building hybrid systems: GLM-5 for architecture design and test generation, MiniMax for implementation. This “cognitive division of labor” represents the actual future of AI development, not monolithic models that do everything poorly.

Deployment Reality Check

Running these beasts locally remains a challenge. GLM-5 requires 8 GPUs with tensor parallelism and 85% memory utilization. The FP8 version still demands serious hardware:

# GLM-5 deployment with vLLM

vllm serve zai-org/GLM-5-FP8 \

--tensor-parallel-size 8 \

--gpu-memory-utilization 0.85 \

--speculative-config.method mtp \

--tool-call-parser glm47 \

--reasoning-parser glm45 \

--enable-auto-tool-choice \

--served-model-name glm-5-fp8MiniMax M2.1 runs on more modest hardware, 128GB RAM gets you the full model, and quantized versions fit on 64GB. For developers with Mac M4 Max machines, MiniMax’s unified memory efficiency makes it the practical choice. As one engineer noted, unified memory is “cheat code for LLMs.”

The cloud deployment story is more interesting. GLM-5 integrates with Z.ai’s coding plan, consuming more quota than GLM-4.7 but providing agent mode with built-in document creation skills. MiniMax slots into existing agent frameworks through OpenRouter and standard APIs, making it the path of least resistance for existing workflows.

The Hardware Advantage Nobody Talks About

GLM-5’s support for non-NVIDIA chips, including Huawei Ascend, Moore Threads, Cambricon, Kunlun, MetaX, Enflame, and Hygon, is a political statement as much as a technical feature. Through kernel optimization and quantization, it achieves “reasonable throughput” on domestic Chinese silicon.

This decoupling from NVIDIA’s ecosystem represents a strategic moat. While Western models optimize exclusively for CUDA, GLM-5’s hardware agnosticism ensures it can scale within China’s semiconductor constraints. It’s a reminder that AI competition is fundamentally about infrastructure independence.

What Developers Are Actually Building

The gap between benchmark performance and real-world utility is where these models live or die. MiniMax M2.1 has earned a “finisher” reputation for building complete CLI tools, debugging its own code, and handling multi-file implementations without human intervention. The cost advantage compounds for teams running agents 24/7.

GLM-5, meanwhile, shines in scenarios requiring architectural documentation and reasoning transparency. Its “interleaved thinking” feature shows the reasoning chain before every response, invaluable for debugging why an agent chose a particular approach. For research teams and safety-critical applications, this visibility is non-negotiable.

The developer experience split is stark: MiniMax for shipping products, GLM for solving puzzles. Many teams now use both, routing tasks based on complexity and cost constraints. This hybrid approach mirrors how Kimi K2.5’s 100 sub-agents orchestrate parallel workstreams, suggesting the future is less about single models and more about intelligent routing layers.

The Bottom Line: Choose Your Fighter

The GLM-5 vs MiniMax M2.5 battle isn’t about which model is “better.” It’s about what you value: architectural depth or execution velocity, reasoning transparency or cost efficiency, system design or task completion.

GLM-5 represents the perfectionist’s path, thoughtful, transparent, occasionally over-engineered. MiniMax embodies pragmatic shipping, cheap, fast, relentlessly focused on the finish line. The fact that both emerged from Chinese labs within 24 hours signals a market mature enough to support simultaneous specialization.

For developers building agentic systems today, the playbook is clear:

– Use GLM-5 for planning, architecture, and scenarios where understanding “why” matters

– Deploy MiniMax for high-volume execution, long-running tasks, and cost-sensitive operations

– Implement routing logic that sends each task to the right cognitive tool

The agent war isn’t about monopoly, it’s about orchestration. And China’s AI labs are writing the manual in real-time.

The real question isn’t which model wins. It’s whether Western AI companies can adapt fast enough to compete with an ecosystem that ships specialized, production-grade agents while they’re still debating safety frameworks.