A commit on December 3rd, 2025, turned a massive swath of cloud-native infrastructure into a ticking clock.

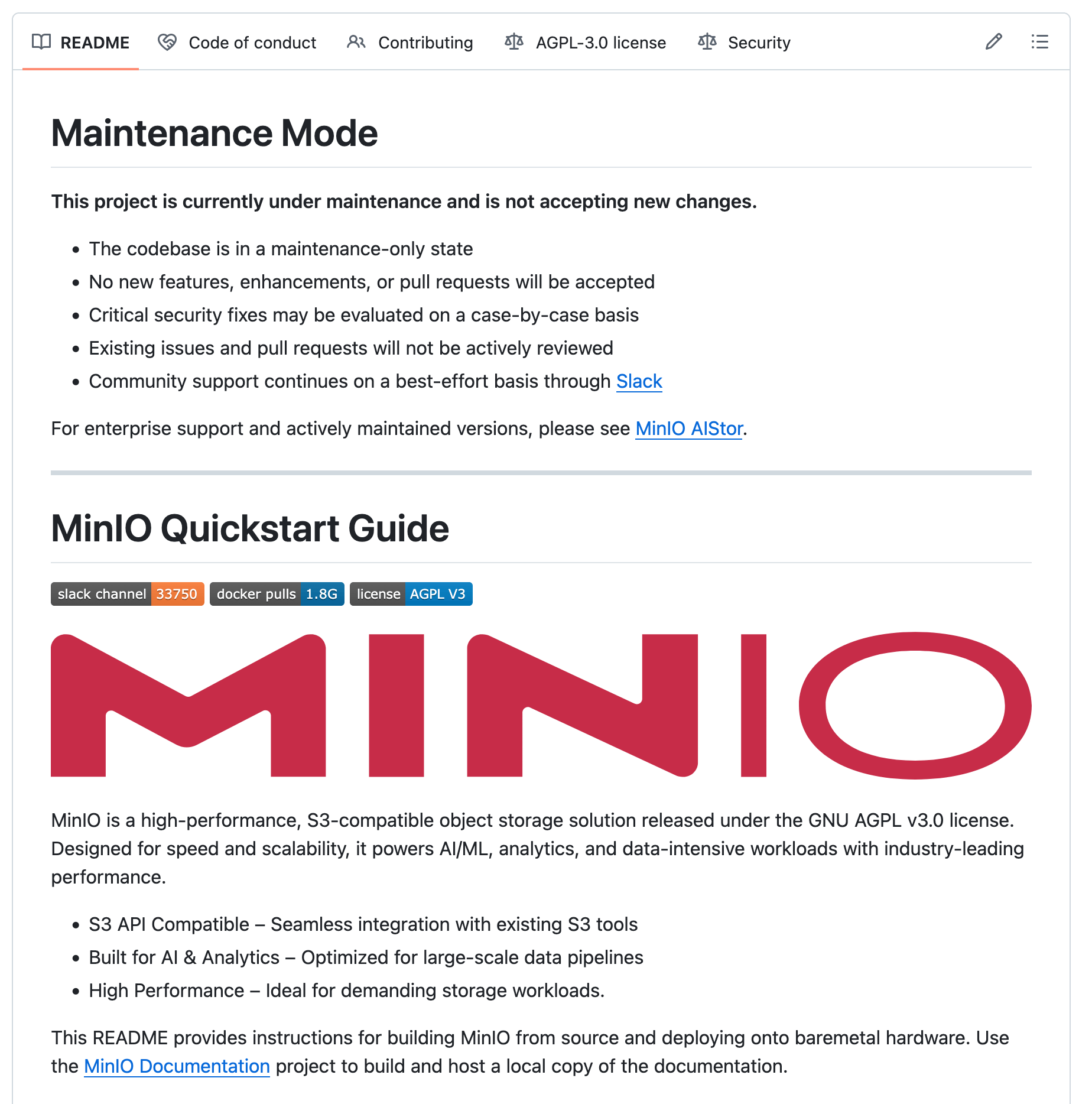

The change to MinIO’s README was stark and direct:

> This project is currently under maintenance and is not accepting new changes.

- The codebase is in a maintenance-only state

- No new features, enhancements, or pull requests will be accepted

- Critical security fixes may be evaluated on a case-by-case basis

- Existing issues and pull requests will not be actively reviewed

- Community support continues on a best-effort basis

The simple message links users to “MinIO AIStor”, a new enterprise offering, closing the loop on a long-running “open-core” playbook. For architects who built systems around S3-compatible APIs and Kubernetes operators, this isn’t just an inconvenience, it fractures a foundational layer of trust. The maintenance mode announcement isn’t a graceful sunset, it’s the sudden vanishing of the roadmap for a project powering thousands of private clouds and CI/CD pipelines.

The Gradual Decay: A Familiar “Own-Core” Playbook

This move wasn’t a surprise, it was a strategic culmination. The fissure started months earlier, in June 2025, when MinIO stripped the web UI out of its Community Edition. The management features developers relied on, bucket creation, lifecycle policy settings, user and account management, suddenly became enterprise-only perks behind a hefty $96,000-a-year paywall for 400TB. The sentiment across forums was unified: this felt like an anti-pattern, a deliberate crippling of the free product.

The scenario echoes a now-familiar pattern: attract a userbase with a fully-featured open-source product, build critical mass, then systematically shift core functionality to a proprietary, paid offering. It’s a model followed by HashiCorp, Elastic, MongoDB, and Redis. The decision is understandable from a business standpoint, funding 58k-star projects with 559 non-company contributors isn’t free, but it’s architecturally ruinous for those who built on the “free” promise.

The discussion points to a deeper, unsettling requirement in MinIO’s contribution process. A PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE discovered by users stipulated that contributors license their code to MinIO only under Apache 2.0, while the project’s outbound license was AGPLv3. This created a legally asymmetrical situation, allowing MinIO to potentially relicense contributions for commercial use, while the community only ever got the copyleft version. It was a de facto CLA, a warning sign many missed.

The Ripple Effect: Downstream Systems Left Hanging

The immediate fallout plays out in the dependency graphs of countless downstream projects. Within hours of the announcement, projects like Comet ML’s Opik were opening issues asking, “Given Minio is part of the self-hosted stack, I was wondering what the plan is for this in the longer term?” It’s a question echoing in Slack channels and deployment manifests everywhere.

For systems architects, MinIO wasn’t just an S3 option, it was the S3 option for on-premise and hybrid cloud deployments. Its lightweight footprint and Kubernetes-native design made it the default choice for CI/CD artifact storage, ML model repositories, and internal data lakes. The “maintenance-only” status introduces a long-term, compounding risk: without security updates and no new features, it becomes a static, vulnerable component in a dynamic infrastructure.

The debate now shifts to practical triage. Do you stay or migrate? The MinIO codebase is stable, and the AGPL license means it can be forked. But maintaining a complex distributed storage system is no small feat. As one developer put it, storage “is a critical component.” The prospect of having to understand MinIO’s internal “file format to fix corruption issues by hand” is a terrifying new operational burden no one signed up for.

The Ecosystem Shuffle: Evaluating the Contenders

Naturally, the market doesn’t remain a vacuum. The scramble for alternatives is already intensely practical, focused on S3 API compatibility, operational simplicity, and crucially, licensing and governance.

- SeaweedFS is emerging as a strong contender. Its creator announced he is now working on it full-time, and recent benchmarks show it leading in several performance categories. However, its history includes a notable volume of bug fixes for core code paths, which gives some adopters pause about its maturity for mission-critical data.

- Garage, developed by the French collective Deuxfleurs, is praised for its simplicity (written in Rust, easy to deploy) and its AGPLv3 license. It’s seen as the “spiritual successor” for hobbyists and small clusters, though it’s noted to be less performant at high speeds compared to MinIO.

- Ceph’s RGW (RADOS Gateway) is the enterprise-grade, battle-tested heavyweight. It’s part of a massive software-defined storage system used by cloud providers. Its complexity and resource requirements are significant, making it overkill for a simple three-node cluster but ideal for large-scale deployments.

- RustFS is a new, aggressively marketed entrant. It promises high performance but is considered immature, with reports of breaking S3 client compatibility and a controversial Contributor License Agreement (CLA) that requires full copyright assignment, a red flag for many in the community.

The licensing model itself becomes a key selection criteria. Projects like Garage (AGPLv3) and SeaweedFS (Apache 2.0) offer more predictable futures than the “own-core” model. The discussion highlights a painful lesson: the license and the governance model are now first-class architectural concerns, not legal footnotes.

The Core Architectural Dilemma: S3 as a De Facto Standard

This crisis exposes a deeper irony: the industry has coalesced around S3’s API as a de facto standard for object storage, yet that API is a moving, proprietary target owned by Amazon. Every “S3-compatible” implementation is a reverse-engineered approximation, chasing a 3,874-page specification PDF that grows with every AWS feature launch.

Implementing the full S3 API is a Herculean task. As one commenter noted, S3 has “three independent permissions mechanisms” and its authentication relies on an “obtuse and idiosyncratic signature algorithm.” Many alternatives, like Garage, consciously implement only a core subset, forcing developers to audit their dependency on more esoteric S3 features. This fragmentation means there is no true drop-in replacement, every migration requires compatibility testing.

This lock-in isn’t just commercial, it’s conceptual. We’ve built an entire generation of software, from data pipelines to web applications, against an API controlled by a single vendor, leaving us vulnerable when the open-source implementations of that API falter.

The Fork in the Road: Maintenance vs. Abandonment

So, what’s the actual risk? Maintenance mode is not abandonment. The code remains AGPLv3 licensed, and critical security fixes might still be merged. For many stable deployments, the software will continue to work. The real danger is strategic stagnation.

New hardware won’t be optimized. New Kubernetes features or security standards won’t be integrated. The project will slowly drift out of sync with the ecosystem. As one pragmatic user noted, they’ve been running the same MinIO version for five years without issue. For them, the change is irrelevant.

But for anyone planning for the next five years, the calculus has irrevocably shifted. The project’s trajectory is no longer aligned with the community’s needs but with its commercial product, “MinIO AIStor.” The pivot to AI-branded storage is a clear market signal: the dollars are in AI workloads, not in supporting the open-source community that got them there.

Conclusion: Recalibrating Trust in Infrastructure

The MinIO saga is a stark reminder that in the world of critical infrastructure, licenses and business models are as important as latency and throughput. It forces a sobering re-evaluation:

- Audit Your Dependencies: For every piece of infrastructure software, ask: Who maintains it? What is their business model? What’s the license? Could we maintain a fork if needed?

- Prioritize Community-Driven Projects: Favor projects governed by foundations (CNCF, Apache) or structured as collectives (like Deuxfleurs). While not immune to change, they offer more predictable governance than single-vendor “own-core” models.

- Design for Portability: Implement storage interfaces, not vendor-specific clients. Test your systems against multiple S3-compatible backends to ensure you’re not accidentally relying on a proprietary extension.

- Accept the Tax: Sometimes, the “free” option carries the highest long-term risk. Budgeting for a paid, supported version of a critical component, or allocating internal resources to maintain a fork, is a legitimate cost of doing business.

The commit that placed MinIO into maintenance mode didn’t just change a README file. It altered the risk profile for a significant portion of the cloud-native stack. The scramble for alternatives isn’t panic, it’s the sound of an industry learning that there is no truly free lunch, especially when it comes to the durable storage of your most valuable data. The real work begins now: rebuilding not just our storage layers, but our trust in the foundations they’re built upon.