Microsoft Fabric’s $2B Growth: Real Innovation or Just Power BI Revenue in a Trench Coat?

Microsoft executives have been celebrating Fabric’s meteoric rise, touting $2 billion in annual recurring revenue achieved in less than two years. The LinkedIn posts practically write themselves: “fastest growing analytics platform”, “unprecedented adoption”, “digital transformation accelerator.” But peel back the marketing veneer and you’ll find a more cynical story, one of forced migrations, opaque accounting, and a strategy that looks less like innovation and more like revenue reassignment.

The core question isn’t whether Fabric is generating $2B. It’s whether that money represents new value creation or simply money that used to be labeled “Power BI Premium” now wearing a Fabric name tag.

The Great Power BI Premium Disappearing Act

Let’s rewind to 2022. Microsoft’s financials explicitly called out Power Platform revenue at $2 billion, growing at 72% year-over-year. Fast forward to today, and “Power Platform revenue” has vanished from earnings calls. Instead, we’re told Fabric, a product that didn’t exist in its current form two years ago, magically hit the same $2B milestone, albeit at a slightly slower 60% growth rate.

The timing is suspiciously convenient. As one partner pointed out, Microsoft “forced all existing Power BI premium capacity subscribers to move to Fabric by simply retiring Power BI Premium licenses.” This wasn’t a gentle nudge, it was a forced march. Organizations running Power BI Premium P1 capacities found themselves automatically migrated to Fabric F64 SKUs, with billing changes that left many finance teams scratching their heads.

The mechanics are straightforward: Premium P1 ($4,000/month) maps to Fabric F64 ($5,000+ depending on usage). Same capacity, different label, higher price. Microsoft’s own documentation confirms this migration path, but what they don’t highlight is how this artificial inflation creates the illusion of organic growth. When you retire a product and force customers onto a more expensive replacement, you’re not innovating, you’re harvesting.

Financial Engineering Masquerading as Product Innovation

Microsoft’s overall financial health is undeniable. With revenue growing from $168.1B in 2021 to $281.7B in 2025, the company has mastered the art of monetizing its ecosystem. Server Products and Tools now generate $98.4B annually, while Microsoft 365 Commercial contributes another $87.8B. In this context, $2B for Fabric seems almost modest, until you realize it’s likely recycled revenue.

The strategy mirrors Microsoft’s Azure playbook from years past. As one veteran architect noted on community forums, Microsoft “moved unrelated, previously adopted products under the Azure umbrella and said ‘see how fast people are adopting Azure!'” The same playbook is unfolding with Fabric: bundle existing services, rebrand them, and claim explosive growth.

What makes this particularly galling for enterprise architects is the lack of genuine choice. Organizations invested heavily in Power BI, building semantic models, training users, embedding analytics into business processes. When Microsoft retired Premium licenses, these companies didn’t evaluate Fabric against competitors, they performed a financially-driven migration to maintain existing functionality. That’s not adoption, that’s lock-in.

The Real Cost: Sticker Shock in the Enterprise

The financial impact extends beyond simple SKU mapping. Consider the experience of one organization that migrated from Power BI Premium P1 ($4,000/month) to Fabric F64. Their monthly costs “significantly increased” despite using only Power BI workloads. The additional Fabric capabilities, Lakehouse, Notebooks, Data Engineering, sat unused while the bill climbed.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Data teams are paying for a Ferrari and only driving it to the grocery store. Worse, attempts to right-size are met with licensing traps. Downgrading to F32, the logical equivalent of their original P1 capacity, would prevent free Power BI license users from accessing reports. To maintain the same access levels they had before, organizations must stay on F64 or higher.

The community has identified workarounds, but they’re band-aids on a broken pricing model. Some recommend automating pause/resume schedules to reduce runtime costs. Others suggest reserved capacity to lock in discounts. But these strategies miss the fundamental issue: Microsoft engineered a situation where maintaining existing functionality costs more, then celebrated the resulting revenue as proof of innovation.

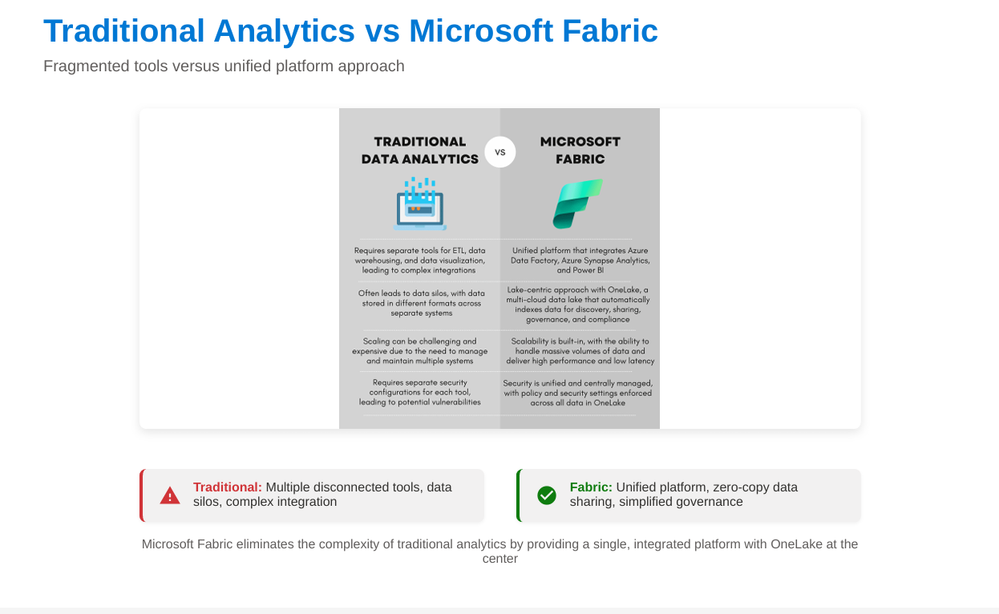

Technical Integration or Strategic Bundling?

Fabric’s architecture tells part of the story. The platform centers on OneLake, a unified data lake that serves as “OneDrive for data.” Power BI integrates natively, accessing shared semantic models and eliminating duplicate datasets. For organizations already deep in the Microsoft ecosystem, this integration has genuine value.

The unified approach solves real problems: data silos, governance challenges, and tool sprawl. For Power BI developers, the transition feels natural, most building blocks are familiar, just reorganized. The Fabric community blog emphasizes this point: “Microsoft Fabric is not replacing Power BI, it’s elevating it.”

But here’s where the narrative fractures. While Microsoft talks about “elevation”, partners describe “opaque” pricing that masks “lack of Fabric adoption.” The performance limitations with non-Microsoft data sources remain, and concurrent query limits don’t scale proportionally with the more expensive F SKUs. It’s a familiar Microsoft pattern: excellent within the walled garden, painful outside it.

The question isn’t whether Fabric has technical merit, any platform that unifies analytics workloads has potential. The question is whether the $2B figure represents customers choosing Fabric for its capabilities, or customers paying more for the same Power BI functionality they had yesterday. Microsoft Fabric’s enterprise adoption and real-world performance beyond marketing claims reveals a more nuanced picture where production readiness varies dramatically by use case.

The Industry’s Verdict: Skepticism and Resignation

Data engineering forums reveal deep skepticism. The prevailing sentiment suggests Microsoft is “making the numbers as opaque as possible to cover the lack of Fabric adoption.” This isn’t coming from competitors or open-source zealots, it’s from the architects and engineers implementing these platforms.

The career implications are significant. Internal team debates over Fabric’s role in professional data engineering careers show professionals questioning whether Fabric expertise represents genuine skill development or vendor-specific credentialing. When a platform’s growth is driven by forced migration rather than technical superiority, resume bullets start to look like compliance rather than capability.

Comparisons to best-of-breed alternatives highlight the gap. Comparing Microsoft Fabric against best-of-breed platforms like Snowflake in the low-code era demonstrates that while Fabric offers convenience, specialists consistently outperform in key areas. The trade-off isn’t between good and better, it’s between integrated and excellent.

Enterprise Architecture at a Crossroads

For architects planning their analytics future, Fabric presents a dilemma. The platform’s unified vision is compelling: one storage layer, one security model, one billing experience. In practice, this often means one throat to choke, with Microsoft holding the leash.

The challenges of moving from exploratory notebooks to production pipelines in platforms like Fabric expose architectural tensions. Fabric’s notebook experience, built on Spark, inherits all the classic problems: environment management, dependency hell, and the chasm between experimentation and operationalization. The promised simplicity masks underlying complexity that doesn’t vanish, it just moves.

Meanwhile, the broader ecosystem evolves. Emerging lightweight ETL tools like Polars versus Spark within the Delta Lake and Fabric ecosystem shows alternatives that challenge Fabric’s performance claims. When a single-machine Polars workflow outperforms distributed Spark for moderate datasets, the justification for Fabric’s premium pricing weakens.

The Innovation Litmus Test

Real innovation creates new value. It solves problems that couldn’t be solved before. It expands markets rather than redistributing existing spend within them. By these measures, Fabric’s $2B claim fails basic scrutiny.

Consider what genuine innovation would look like:

– Power BI users would migrate to Fabric because it enables scenarios previously impossible

– Pricing would reflect usage and value, not arbitrary SKU mappings

– Revenue growth would accompany expanding customer bases, not just deeper extraction from existing ones

Instead, we see:

– Functionality that existed yesterday now costs more today

– Artificial constraints that prevent downgrading without losing basic access

– Revenue numbers that suspiciously match the product Microsoft retired

Even integration of Python with SQL Server and Fabric’s support for modern data workflows, while welcome, represents catch-up more than breakthrough. The broader industry has been here for years, Microsoft is just now making it first-class.

Conclusion: Call It What It Is

Microsoft Fabric may eventually become the platform Microsoft promises. The architecture is sound, the integration points are real, and for organizations committed to the Microsoft stack, it offers genuine convenience. But the $2B revenue figure is not evidence of this success, it’s a mirage created by accounting changes and forced migrations.

The data engineering community deserves honesty. Debates around data transformation patterns relevant to Fabric’s notebook and pipeline workflows should be about technical merit, not licensing survival. Credentialing and skills validation in the growing freelance market for Fabric and Power Platform roles should reflect real expertise, not vendor lock-in endurance.

Microsoft has the resources to build truly innovative products. Azure’s evolution from punchline to powerhouse proves it. But Fabric’s current trajectory, at least as measured by that $2B figure, looks more like financial engineering than technical revolution.

Enterprise architects and data leaders should evaluate Fabric on its actual capabilities, not its claimed revenue. Ask hard questions about performance with non-Microsoft data sources. Test whether the unified platform actually simplifies operations or just centralizes billing. And most importantly, recognize that growth metrics driven by forced migrations tell you more about vendor strategy than product quality.

The fastest-growing analytics platform in history? Maybe. But growth without genuine choice is just corporate strong-arming with better marketing.