A data engineer in an online course recently questioned a fundamental dbt pattern: why split a simple transformation into two CTEs when one would suffice? The instructor’s example showed a model that selected from a source table in the first CTE, then performed all transformations in the final SELECT. The student suggested reversing this, doing the work upfront and ending with a simple SELECT * FROM result_table.

What seems like a minor stylistic preference has ignited a quiet war across data teams. One camp argues for “import-style” CTEs that mirror software engineering patterns, prioritizing readability and maintainability. The other camp sees unnecessary computational overhead, especially in warehouses that don’t optimize away these logical separations. The truth? Both sides are right, and wrong, depending on your warehouse, your data volume, and whether you’re running incremental models.

The Sacred CTE Pattern and Its Discontents

The pattern in question looks like this:

with result_table as (

select * from {{ source('jaffle_shop', 'orders') }}

),

transformed as (

select

order_id,

customer_id,

cast(order_total as decimal(10,2)) as order_amount,

order_date::date as ordered_at

from result_table

)

select * from transformeddbt’s own style guide codifies this approach: import CTEs at the top, named after their source tables, selecting only the columns you need with minimal filtering. The final SELECT should be a simple select * from final_output_cte. This creates a consistent narrative: imports → transformations → output.

But the alternative pattern, what we might call “eager transformation”, is equally valid SQL:

with result_table as (

select

order_id,

customer_id,

cast(order_total as decimal(10,2)) as order_amount,

order_date::date as ordered_at

from {{ source('jaffle_shop', 'orders') }}

)

select * from result_tableSo why does dbt push the first pattern so hard? The answer lies not in performance, but in cognitive load and the DAG.

The Readability Industrial Complex

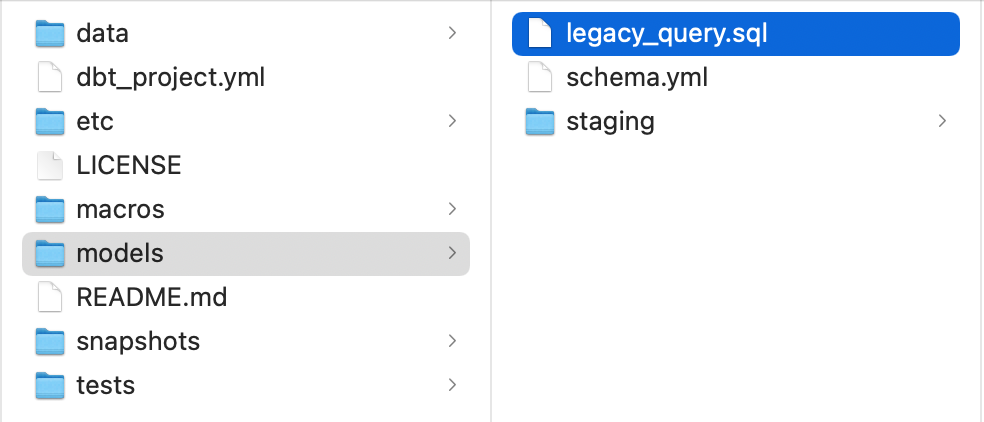

dbt’s core innovation is treating SQL like software. The ref() function creates a dependency graph, and the DAG in dbt docs (where sources appear in green) visualizes this relationship. The import-style CTE pattern extends this philosophy into the model itself: you can “import” your sources at the top, scan through intermediate transformations, and know the final output appears at the bottom.

This consistency pays dividends. When you’re debugging a 200-line model at 2 AM, seeing select * from final_output at the bottom means you immediately know where to look. The pattern also makes it trivial to audit intermediate steps, just change the final SELECT to reference any upstream CTE.

The modularity argument is equally compelling. As best practices documentation notes, when a CTE appears in multiple models, it should become its own model. The import-style pattern makes this refactoring mechanical: lift the CTE, add a config block, and replace the CTE reference with a ref(). The eager transformation pattern obscures these opportunities because the “import” and “transform” steps are fused.

The Performance Ghost in the Machine

Here’s where the sacred cow starts to look less holy. In Snowflake, the first CTE often gets optimized away entirely, unless you reference it multiple times. The Snowflake query planner is smart enough to collapse the logical separation into a single execution plan. But “often” is not “always”, and Snowflake is not every warehouse.

Microsoft Fabric Data Warehouse explicitly does not support nested CTEs in model materialization. The adapter documentation warns that models using multiple nested CTEs may fail during compilation or execution. This isn’t a performance issue, it’s a compatibility wall. Your beautifully readable import-style model might not run at all.

Even in warehouses that support CTEs, the placement of transformations matters profoundly for incremental models. The incremental model configuration guide specifically warns: “For more complex incremental models that make use of Common Table Expressions (CTEs), you should consider the impact of the position of the is_incremental() macro on query performance. In some warehouses, filtering your records early can vastly improve the run time of your query!”

Consider this incremental model:

{{ config(materialized='incremental', unique_key='order_id') }}

with source_data as (

select * from {{ source('jaffle_shop', 'orders') }}

{% if is_incremental() %}

where updated_at > (select max(updated_at) from {{ this }})

{% endif %}

),

transformed as (

select

order_id,

customer_id,

cast(order_total as decimal(10,2)) as order_amount

from source_data

)

select * from transformedThe filter is correctly placed in the import CTE, limiting data scanned early. But if you follow the import-style pattern too rigidly, you might be tempted to put the filter in the transformed CTE, scanning the entire source table before filtering. On a multi-terabyte table, that’s a career-limiting mistake.

When Style Becomes Substance

The performance implications extend beyond incremental models. In warehouses with limited query optimization, each CTE materialization creates a temporary result set. The import-style pattern can double your memory usage: once for the import CTE, once for the transformed output. For small datasets, this is negligible. For models processing billions of rows, it’s a measurable cost.

The intermediate model pattern suggests breaking complex transformations into separate models rather than CTE chains. This approach gives you the readability benefits of the import-style pattern while materializing intermediate results explicitly. You can test each step, optimize materialization strategies per component, and avoid the CTE nesting problem entirely.

But this creates its own tax: model proliferation. A transformation that could live in a single model with three CTEs becomes three separate models, three more entries in the DAG, three more materializations to manage. The marginal cost of an additional model isn’t zero, especially in large projects where the DAG already contains hundreds of nodes.

The Pragmatic Middle Path

The controversy isn’t resolved by picking a side, it’s resolved by recognizing that the import-style CTE pattern is a default, not a dogma. The dbt style guide is correct for 80% of cases, but you need to know when to break it.

Break the pattern when:

1. Warehouse compatibility requires it: If you’re targeting Microsoft Fabric or another warehouse with CTE limitations, fuse your transformations into the import CTE.

2. Incremental filters must be early: Place is_incremental() filters as close to the source as possible, even if it makes your import CTE look like a transformation.

3. Performance testing shows overhead: If query plans reveal unnecessary materialization, collapse the CTEs and measure the improvement.

4. The CTE is only referenced once: A CTE that exists solely for readability and isn’t reused is a candidate for inlining.

Keep the pattern when:

1. Debugging complex logic: The ability to select * from intermediate_cte is invaluable during development.

2. Refactoring is likely: If a transformation might become reusable, keep it separate.

3. Team consistency matters: On large teams, the cognitive savings of a consistent pattern outweigh marginal performance gains.

4. Warehouse optimization is robust: In Snowflake, BigQuery, or other optimizers that handle CTEs well, the performance cost is often zero.

The Real Controversy: Premature Abstraction

The deeper issue isn’t CTE style, it’s premature abstraction. Data engineers, eager to apply software engineering best practices, sometimes abstract too early. The import-style pattern feels clean, so we apply it universally before we have evidence we need it. This is the same impulse that leads to microservices architectures for monolith-sized problems.

The dbt documentation itself has evolved on this point. Earlier versions recommended “base models” as a formal layer, this was moved to opinion guides when the team realized it was prescriptive rather than universal. The current guidance on how to structure projects emphasizes purpose-built transformation steps over rigid layering.

The performance tax of nested CTEs is real, but it’s often dwarfed by other inefficiencies: missing partitions, unnecessary cross-joins, failure to push down predicates. Obsessing over CTE style while ignoring these bigger issues is like tuning a race car’s spoiler when the engine is misfiring.

Your Move: Measure, Don’t Debate

The next time a team member challenges the sacred CTE pattern, resist the urge to defend it on principle. Instead, run dbt compile, examine the query plan, and measure the execution time. In Snowflake, check if the CTE is being optimized away. In Fabric, verify it compiles at all. For incremental models, test filter placement with dbt run --full-refresh vs. incremental runs.

The style vs. performance debate only matters when performance is actually at stake. Most of the time, the import-style pattern is fine. But when it’s not, blind adherence becomes a performance tax you’re paying without realizing it.

And if you do find a case where the eager transformation pattern wins? Document it. Add a comment explaining why you broke the pattern. The next engineer who sees it won’t think you’re ignorant of dbt conventions, they’ll know you measured and made a deliberate choice. That’s the real best practice.

Where do you land on the CTE style spectrum? Have you measured performance differences between these patterns in your warehouse? The debate is far from settled, and the answer likely depends on factors we haven’t even discussed here.