The Copy-Paste Tipping Point: When Duplication Beats Abstraction in Data Pipelines

Every data engineer hits the same wall. You’re building your third API-to-S3 ingestion pipeline this quarter, and that upload_to_s3() function from your last project is staring you in the face. Do you extract it into a shared library? Or do what your reptile brain is screaming: copy, paste, tweak, ship?

The conventional wisdom is clear: duplication is sin, packaging is virtue. But the conventional wisdom was written by software engineers building microservices, not data engineers wrestling with fifty slightly different data sources that all break in subtly unique ways. The real answer is messier, more controversial, and infinitely more useful.

The “Write Everything Twice” Heuristic

Somewhere in the Reddit trenches of r/dataengineering, a pragmatic pattern emerged that cuts through the dogma: Write Everything Twice. Not three times. Twice. The first time you need a function, leave it embedded in your pipeline script. The second time you find yourself writing the exact same logic for the exact same use case, that’s your signal to extract it into a module.

This isn’t laziness, it’s risk management. Premature abstraction is the tax you pay for guessing wrong about what needs to be reusable. A data engineer working on API ingestion learned this the hard way: building a separate package for S3 uploads before you have two working implementations means you’re abstracting over assumptions, not proven patterns. The result? A library that’s too rigid for your third pipeline and too complex for your first two.

The beauty of the “twice” rule is that it forces you to validate the abstraction. By the second implementation, you’ve seen the edge cases. You know which parameters actually vary (bucket names, partition schemes, error handling) and which are stable (retry logic, connection pooling). You’re not designing for hypothetical reuse, you’re refactoring proven duplication.

When Views Make Packages Obsolete

Here’s where the debate gets spicy. One practitioner dropped a truth bomb that triggered collective re-evaluation: people have forgotten views exist. In the rush to Python-ify everything, data engineers are building elaborate module hierarchies for transformations that could live as simple SQL views.

The argument is surgical. That Python module hullabaloo for standardizing ad spend data? A view does it better, faster, and without the dependency hell. Views give you reusability with zero deployment overhead. They live in the warehouse, accessible to every tool in your stack, BI platforms, notebooks, SQL clients. No versioning conflicts, no PyPI credentials, no breaking changes from upstream library updates.

This isn’t a call to abandon Python. It’s a call to remember that packaging decisions span more than PyPI. The most maintainable “package” might be a well-designed view layer that abstracts complexity at the data tier rather than the compute tier. Before you pip install your-internal-utils, ask: could this be a view that lives in dbt?

Speaking of dbt, their package ecosystem reveals the double-edged sword of reusability. The platform’s dispatch patterns and packages like dbt_utils abstract away SQL dialect differences across warehouses. But that abstraction comes at a cost: syntax differences are “even more pronounced” in Python, where “if there are five ways to do something in SQL, there are 500 ways to write it in Python.” The flexibility that makes Python powerful makes Python packages fragile.

The Hidden Iceberg of Packaging

Creating a package feels like a clean solution. It isn’t. The moment you extract that S3 uploader into its own repository, you’ve signed up for:

- Versioning theater: Every “quick fix” now requires a version bump, changelog update, and coordinated upgrade across multiple pipelines

- Dependency whack-a-mole: Your simple utils package pulls in

requests, which conflicts with pipeline A’s pinned version ofurllib3 - The testing burden: Is your change backward-compatible? Better write tests. Did you break pipeline B? Better spin up integration tests across all consumers

- The documentation tax: Code that’s extracted needs docs, examples, and migration guides. Code that lives in a pipeline needs a comment, maybe

This is how teams end up with 47 internal packages, each used by exactly one pipeline, each requiring weekly security patches. The technical debt from ad-hoc data workflows metastasizes into organizational debt: meetings about deprecation timelines, Slack threads about version pins, engineers who spend Friday afternoon debugging a breaking change in internal-data-utils-v3.2.1.

The dlt Hub Alternative

Before you build that package, consider if someone’s already solved your problem without the packaging overhead. The Reddit crowd quickly pointed to dlt (data load tool) as a pattern interrupt. Instead of building your own API-to-S3 abstraction, dlt gives you a declarative framework that handles the boring parts while staying flexible enough for custom logic.

This is the modern twist on the packaging debate: the best package is often someone else’s package. The rise of specialized data engineering frameworks means the abstraction you need might already exist as a well-maintained open-source project. Building your own S3 uploader package is like writing your own HTTP library in 2025. The real skill isn’t packaging, it’s knowing when to adopt.

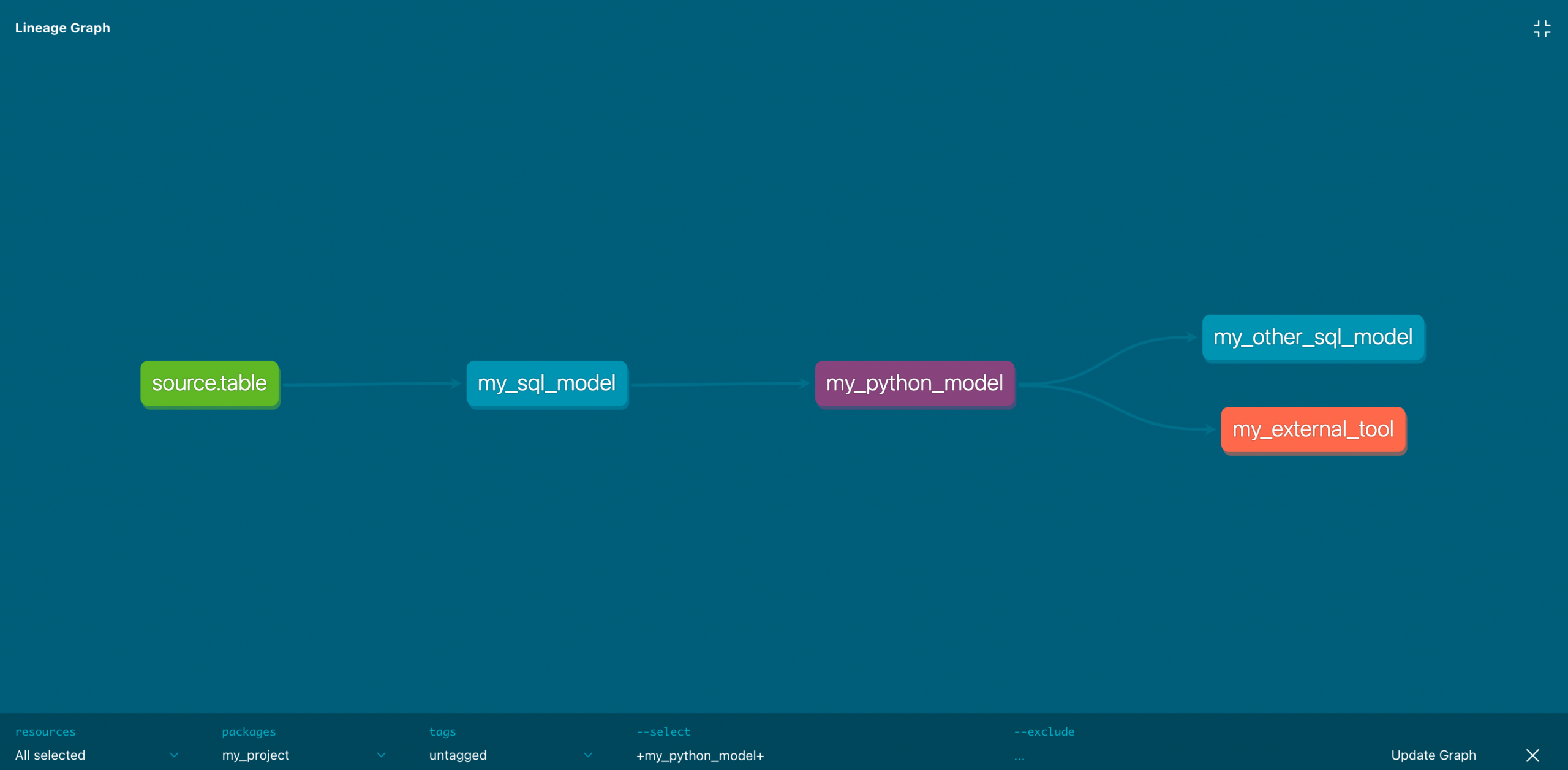

dbt’s Python model ecosystem reinforces this. Their documentation shows how to configure PyPI packages directly in models, treating external dependencies as first-class citizens. The packages config in your Python model becomes a lighter-weight alternative to building internal libraries: dbt.config(packages=["numpy==1.23.1", "scikit-learn"]). You’re still reusing code, but without the maintenance burden of owning it.

The Decision Framework: Four Questions

So when do you package? Ask these:

1. How many consumers? If the answer is “maybe two, eventually”, stop. Two pipelines can copy-paste for a year before the overhead of packaging pays off. Three is the real inflection point, triplication is where duplication becomes unmaintainable.

2. How stable is the abstraction? That S3 uploader seems universal, but wait until you hit the pipeline that needs multipart uploads, another that requires server-side encryption, and a third that uses S3 Express One Zone. If the abstraction isn’t settled, packaging it prematurely creates a fragile interface that needs constant breaking changes.

3. What’s the cost of drift? If pipelines with slightly different S3 logic could corrupt data or cost $50K in storage mistakes, package immediately. If the cost is “someone might spend 30 minutes debugging a minor difference”, let it drift.

4. Can a view do it better? For transformations, aggregation logic, or data standardization, a materialized view in your warehouse beats a Python package every time. It’s reusable, versioned by design, and lives where your data lives.

The Scaling Trap

Here’s the counterintuitive part: packaging decisions that work at 5 pipelines break at 50. A team of three data engineers can coordinate breaking changes over coffee. A team of thirty can’t.

The Reddit discussion surfaced a common failure mode: teams start with heavy packaging too early, then abandon it entirely when the overhead becomes unbearable. They swing from “everything is a shared library” to “every pipeline is a snowflake”, and both extremes create technical debt that compounds.

The solution isn’t a binary choice, it’s a spectrum. Use lightweight reuse mechanisms that match your scale:

- 1-3 pipelines: Copy-paste with comments linking to the “reference implementation”

- 4-10 pipelines: Extract to a shared module within a monorepo, no separate versioning

- 10+ pipelines: Full package with semantic versioning, docs, and a deprecation policy

The dbt Mesh Future

dbt’s answer to this scaling problem is cross-project references via dbt Mesh. Instead of packaging shared code as a library, you package it as a downstream project. Your S3 uploader becomes a dbt project that materializes tables, and other projects reference it via dbt.ref().

This flips the script: reuse happens at the data layer, not the code layer. Your “package” is a contract, a stable table schema that multiple pipelines can depend on. The implementation details stay private, and consumers are insulated from changes as long as the contract holds.

This model shines for large-scale data processing and pipeline design. When you’re moving billions of records, the cost of recomputing in each pipeline dwarfs the overhead of maintaining a shared project. dbt Mesh makes that shared project a first-class citizen rather than an afterthought.

The Verdict

The packaging debate in data engineering isn’t about software engineering best practices, it’s about survival. The right choice is the one that lets you ship today while staying able to debug tomorrow.

Copy-paste isn’t technical debt if you have a plan for triplication. Packaging isn’t virtue if it creates a dependency nightmare. The real skill is knowing which side of the tipping point you’re on.

So the next time you’re staring at that S3 uploader function, don’t ask “should I package this?” Ask: “Will packaging this make it easier to change when the next data source breaks it?” If the answer is yes, package. If the answer is “maybe, but not for a while”, copy-paste with a TODO comment and move on.

Your future self will thank you for the pragmatism. Your teammates will thank you for not adding another internal package to maintain. And your pipelines will thank you by actually working.

The Takeaway: Duplication is cheaper than the wrong abstraction. Wait for the second implementation, question whether a view could solve it, and only package when the overhead of drift exceeds the overhead of coordination. In data engineering, the best code is often the code you don’t have to write, or maintain.