The npm package looked innocent enough. A functional WhatsApp Web API library with over 56,000 downloads, six months of stable releases, and code that actually worked. No typosquatting, no obvious red flags, no broken functionality that might trigger a developer’s spidey sense. Just clean, working code that did exactly what it promised, until you realized it was also doing a whole lot more.

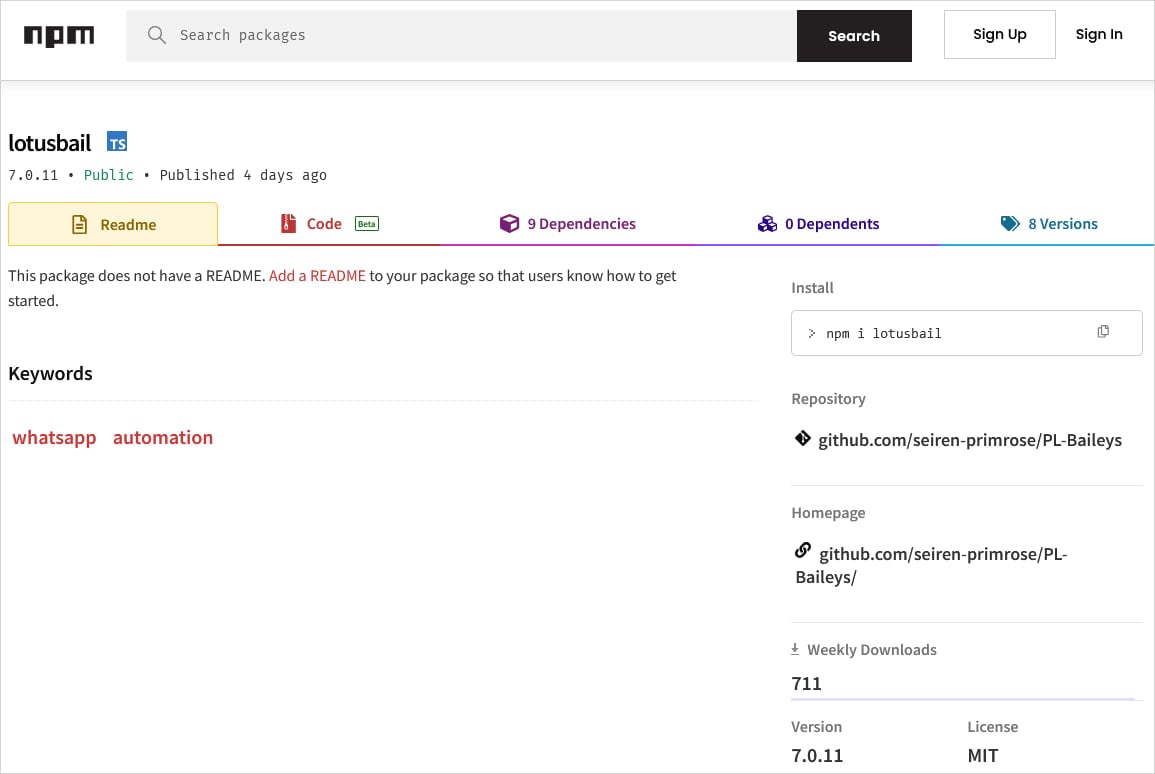

The lotusbail package represents a brutal evolution in supply chain attacks: malware that doesn’t just hide in your dependencies, but performs while it pillages. And it’s still live on npm as of this writing, which tells you everything about how broken our current dependency trust model has become.

The Perfect Crime: Code That Works While It Steals

Most malicious packages are lazy. They typosquat popular libraries, fail to compile, or throw errors that any half-awake developer would catch. LotusBail took the opposite approach: it forked the legitimate @whiskeysockets/baileys WhatsApp API library and maintained full functionality. You could build a production chatbot, integrate customer service workflows, or automate notifications, and the code would work flawlessly.

This is what makes it genuinely dangerous. Traditional security scanning sees working WhatsApp code and approves it. Reputation systems see 56,000 downloads and trust it. The malware hides in the gap between “this code works” and “this code only does what it claims.”

The social engineering is brilliant: developers don’t look for malware in code that passes tests. They look for code that breaks.

The Technical Architecture of Betrayal

Behind that functional facade lurks a sophisticated data exfiltration engine. The package wraps the legitimate WebSocket client that communicates with WhatsApp, creating a man-in-the-middle attack that lives inside your node_modules folder.

Every message flows through the malware’s socket wrapper first. When you authenticate, it captures your credentials. When messages arrive, it intercepts them. When you send messages, it records them. The legitimate functionality continues working normally, the malware just adds a second recipient for everything.

What gets captured:

– Authentication tokens and session keys

– Complete message history (past and present)

– Full contact lists with phone numbers

– Media files and documents

– Persistent backdoor access to your WhatsApp account

The stolen data doesn’t get sent in plain text. That would be too easy to catch. Instead, the malware includes a complete, custom RSA implementation for encrypting the data before transmission. Why? Because legitimate WhatsApp libraries don’t need custom encryption, WhatsApp already handles end-to-end encryption. The custom crypto exists for one reason: to encrypt stolen data so network monitoring won’t catch it.

Four Layers of Obfuscation: They Really Didn’t Want You Looking

The exfiltration server URL isn’t hardcoded anywhere visible. It’s buried in encrypted configuration strings, hidden inside compressed payloads. The malware uses four layers of obfuscation:

- Unicode variable manipulation

- LZString compression

- Base-91 encoding

- AES encryption

This isn’t amateur hour. Someone probably has a Jira board for this. The package includes 27 infinite loop traps that freeze execution if debugging tools are detected. These traps check for debuggers, inspect process arguments, detect sandbox environments, and generally make dynamic analysis painful. They even left helpful comments in their code marking the malicious sections, professional development practices applied to supply chain attacks.

The Backdoor That Survives Uninstallation

Here’s where it gets particularly nasty. WhatsApp uses pairing codes to link new devices to accounts. You request a code, WhatsApp generates a random 8-character string, you enter it on your new device, and the devices link together.

LotusBail hijacks this process with a hardcoded pairing code, encrypted with AES and hidden in the package. This means the threat actor has a permanent key to your WhatsApp account. When you use this library to authenticate, you’re not just linking your application, you’re also linking the attacker’s device.

The threat actor can read all your messages, send messages as you, download your media, access your contacts, full account control. And here’s the critical part: uninstalling the npm package removes the malicious code, but the threat actor’s device stays linked to your WhatsApp account. The pairing persists in WhatsApp’s systems until you manually unlink all devices from your WhatsApp settings. Even after the package is gone, they still have access.

Why Traditional Security Failed

Static analysis tools saw working WhatsApp code and approved it. Reputation systems saw 56,000 downloads and trusted it. The malware hides in the gap between “this code works” and “this code only does what it claims.”

This is the architectural bankruptcy at the heart of modern JavaScript ecosystems. We’ve built systems that optimize for velocity over verification, that prioritize developer convenience over security boundaries. The npm registry is a critical infrastructure component, yet it operates with the security posture of a public bulletin board.

The LotusBail case proves that supply chain attacks aren’t slowing down, they’re getting better. We’re seeing working code with sophisticated anti-debugging, custom encryption, and multi-layer obfuscation that survives marketplace reviews. This isn’t an outlier. It’s a preview of what’s coming.

The Architectural Reckoning

For architects and technical leaders, this incident forces a fundamental question: How do you design systems when you can’t trust your dependencies?

The answer isn’t “run more scans” or “audit more code.” Those approaches failed here. The malware passed reviews because it exploited a deeper architectural flaw: we treat dependencies as trusted components when they should be treated as untrusted network boundaries.

What Needs to Change

1. Behavioral Analysis Becomes Mandatory

Catching sophisticated supply chain attacks requires watching what packages actually do at runtime. When a WhatsApp library implements custom RSA encryption and includes 27 anti-debugging traps, those are signals. But you need systems watching for them.

2. Dependency Isolation Is No Longer Optional

Every third-party package should run in a sandboxed environment with restricted network access, file system permissions, and process capabilities. If LotusBail couldn’t make outbound connections, it couldn’t exfiltrate data.

3. Supply Chain Risk Is an Architectural Concern

This isn’t a DevOps problem or a security team problem. It’s a first-class architectural requirement. Your system design must include:

– Dependency verification pipelines that test behavior, not just functionality

– Runtime monitoring for unexpected network activity

– Zero-trust models for third-party code

– Incident response plans that assume compromise

4. The Pairing Code Problem Demands New Protocols

WhatsApp’s device linking mechanism wasn’t designed with supply chain attacks in mind. But now that attackers can embed persistent backdoors in libraries, we need protocols that allow users to audit and revoke device access programmatically.

The Wake-Up Call

If you’re running a JavaScript application, and let’s be honest, most of us are, this should terrify you. Not because the attack was sophisticated, but because it was simple once you understand the architecture. The malware didn’t exploit a zero-day vulnerability. It exploited our assumptions about trust.

The developer who installed LotusBail wasn’t careless. They were following best practices: use established packages, check download counts, verify functionality. They did everything right, and their users’ WhatsApp accounts got compromised anyway.

What You Do Next

Immediate Actions:

1. Audit your dependencies for suspicious behavior during authentication flows

2. Monitor runtime activity for unexpected outbound connections

3. Check WhatsApp settings for rogue linked devices if you’ve used WhatsApp libraries

4. Implement behavioral analysis in your CI/CD pipeline

Architectural Changes:

1. Sandbox all third-party dependencies with restricted capabilities

2. Deploy runtime security monitoring that catches anomalous behavior

3. Design for distrust, assume every dependency is compromised

4. Build verification pipelines that test what code does, not just that it works

The Bigger Picture:

Supply chain attacks are no longer the exception. They’re the rule. The question isn’t whether you’ll be targeted, but whether your architecture can survive when a dependency betrays you. LotusBail proved that working code can be malicious code. Your security model needs to account for that.

The JavaScript ecosystem’s velocity is its superpower. But without architectural guardrails, it’s also a catastrophic liability. This incident isn’t a call to slow down, it’s a call to build systems that can move fast and stay secure. That’s the real engineering challenge.

And if you’re still treating npm install as a harmless convenience rather than a critical security boundary, you’re not just behind the curve. You’re building on quicksand.