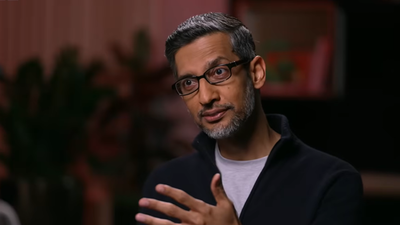

When AI’s electricity appetite grows so voracious that Earth’s power grids can’t keep up, where does the industry turn? The answer, according to Google CEO Sundar Piachai, is straight up.

In what he describes as a “crazy example” of long-term thinking, Pichai confirmed “Project Suncatcher”, Google’s plan to deploy Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) into orbit by 2027. This isn’t theoretical research, it’s a direct response to AI’s infrastructure crisis reaching escape velocity.

The Energy Math That Broke Earth

The numbers driving this orbital exodus are staggering. Current global data center capacity sits at approximately 59 gigawatts, but AI’s exponential growth trajectory threatens to overwhelm existing infrastructure. The pattern across tech giants reveals the scale of the problem:

- Microsoft is restarting nuclear plants

- Amazon is buying gas-powered energy assets

- Google is planning to leave the planet entirely

As Pichai noted in his conversation with Google DeepMind’s Logan Kilpatrick, the company had to significantly ramp up data centers and hardware to meet AI demand, experiencing capacity shortages that forced this infrastructure reckoning.

The Orbital Advantage: Why Space Makes (Some) Sense

The case for orbital computing revolves around three fundamental advantages that Earth simply can’t match.

Continuous Solar Power: A solar panel in space generates roughly 5x to 8x more total energy per day than equivalent terrestrial panels. In dawn-dusk sun-synchronous low-Earth orbit, satellites receive nearly continuous sunshine without atmospheric interference or night cycles.

Radiation Cooling: The vacuum of space offers a thermal management advantage that’s frequently misunderstood. Rather than conventional “cold”, space provides perfect radiative cooling conditions. As Google’s research paper outlines, heat rejection happens through radiation rather than convection, eliminating dependence on water cooling systems that are becoming increasingly scarce and politically contentious.

Infinite Real Estate: Space offers unlimited expansion potential without local resistance, zoning disputes, or NIMBY battles over data center construction. Google’s technical paper describes “constellations of satellites packing Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) in tight formation” that could scale to terawatts of compute capacity within the orbital band.

The Technical Reality Check

Despite the visionary appeal, serious engineering challenges separate Project Suncatcher from practical implementation.

Cooling Isn’t Simple: The common perception that “space is cold” misses crucial thermal dynamics. Without air or water for convection cooling, heat dissipation happens solely through radiation, requiring massive radiator surfaces. Google’s approach uses “heat pipes and radiators while operating at nominal temperatures”, but scaling this to data-center levels presents unprecedented thermal engineering challenges.

Radiation Hardening: Google’s radiation testing revealed that their V6e Trillium Cloud TPUs can survive a total ionizing dose equivalent to a 5-year mission without permanent failures. However, High Bandwidth Memory subsystems showed sensitivity, with stress tests revealing irregularities after 2 krad(Si), nearly triple the minimum requirement for low-Earth orbit survival. Single Event Effects causing bit-flip errors remain a concern for training workloads where undetected corruption could compromise model integrity.

The Repair Problem: As critics on developer forums pointed out, you can’t send a technician to swap out failed hardware in orbit. Google’s solution? “Redundant provisioning”, essentially overbuilding with extra processors and satellites to compensate for inevitable failures. The company acknowledges that failed TPUs are “manually replaced by technicians on Earth, which is relatively simple and low-cost… but obviously impracticable in space.”

The Launch Economics: When $200/kg Changes Everything

Google’s analysis projects that if launch costs to low-Earth orbit reach $200/kg by the mid-2030s, the economics become compelling. At that price point, the “launched power price”, the cost of delivering solar power capacity to orbit, could reach approximately $810/kW/year for Starlink v2-type satellites.

Compare this to terrestrial data centers, where annual power costs range from $570-3,000/kW/year depending on regional electricity prices and power usage effectiveness. The math suddenly makes orbital computing look less like science fiction and more like strategic infrastructure planning.

SpaceX’s Starship could potentially drive costs even lower, the analysis suggests that with 10x component reuse, launch costs might drop to ~$60/kg, fundamentally rewriting the orbital economics playbook.

Networking at Orbital Speeds

Perhaps the most ambitious technical challenge involves creating a data center where the components are moving at 17,500 mph relative to each other.

Google’s vision involves satellites flying in “close proximity” with “inter-satellite links using free-space optics” to enable the high-bandwidth, low-latency communication required for distributed AI training. Their bench-scale demonstrator achieved 800 Gbps unidirectional (1.6 Tbps bidirectional) transmission across short free-space paths.

The proposed architecture uses dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) with commercial off-the-shelf transceivers, potentially supporting 9.6 Tbps bidirectional bandwidth per aperture. To achieve these staggering data rates, satellites would maintain formation flight with distances as close as 2.5 kilometers between nodes, enabling spatial multiplexing that scales bandwidth inversely with distance.

The Competitive Landscape Heats Up

Google isn’t alone in eyeing the orbital frontier. Y Combinator-backed startup Starcloud is preparing to launch what it calls the “world’s first commercial space-based data center modules” in late 2025, promising 5GW of solar-powered capacity that could slash energy costs by up to 10x compared to terrestrial facilities.

NVIDIA has highlighted Starcloud’s progress, noting their H100-powered satellite already tested in space, delivering “sustainable high-performance computing beyond Earth.” The company claims their approach cuts energy requirements by 90% even after accounting for launch costs.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk envisions Starship delivering “around 300 GW per year of solar-powered AI satellites to orbit, maybe 500 GW”. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has speculated about building “a big Dyson sphere on the solar system” for AI computation, while Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff noted space offers “continuous solar and no batteries needed.”

The 2027 Reality Check

It’s crucial to understand what Google actually plans to deploy by 2027. Despite the ambitious vision, Pichai’s actual commitment is measured: “in 2027, hopefully we’ll have a TPU somewhere in space”. This initial deployment will essentially be a proof-of-concept, a far cry from the full-scale orbital data centers the research paper describes.

As some observers noted, this resembles “tossing two smartphones into orbit and seeing if they can run full tilt using solar panels” rather than immediately building orbital server farms. The project follows Google’s established pattern of ambitious research initiatives with phased technological goals.

The Infrastructure Arms Race

Project Suncatcher represents more than just technological ambition, it’s a stark admission that AI’s exponential growth has hit fundamental terrestrial constraints. When the planet itself becomes the limiting factor, the logical progression is upward.

The initiative reveals several uncomfortable truths about AI’s scaling trajectory:

- Energy consumption is growing faster than efficiency improvements

- Geographic constraints are becoming binding limitations

- Thermal management is approaching physical limits

- Economic scaling requires fundamentally new approaches

As Pichai himself acknowledged, the concept seems “crazy today, but when you truly step back and envision the amount of compute we’re going to need, it starts making sense and it’s a matter of time.”

The real question isn’t whether orbital computing is feasible, the physics and economics are rapidly converging to make it inevitable. The question is whether we’re building the most expensive computing infrastructure ever conceived, or whether this represents the logical next step in humanity’s computational evolution.

One thing’s certain: when Earth becomes too small for your AI models, the only direction left is up. And Google’s TPUs might just be the first settlers in this new computational frontier.