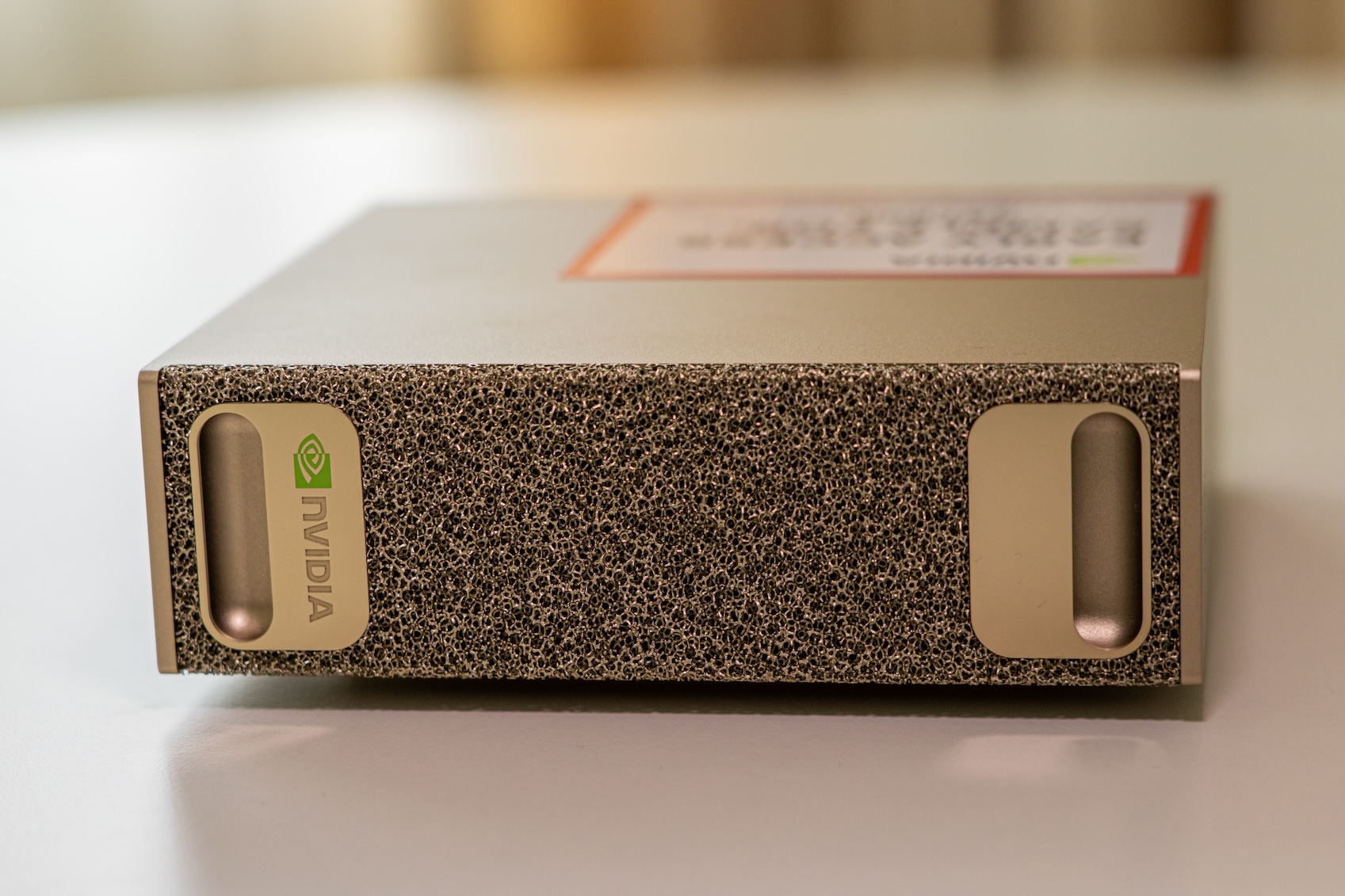

The AI community is divided over a tiny gold box. On one side, doctoral students claim it’s their ticket to competing with Big Tech. On the other, performance analysts call it a $4,000 paperweight. The truth? Both are right, and that’s exactly why NVIDIA’s DGX Spark might be the most consequential piece of AI hardware in years.

The Reddit Confession That Started It All

A doctoral student in a small research group recently posted what many considered heresy: their lab was using a DGX Spark to prototype and train foundation models, declaring they could “finally compete with groups that have access to H100s or H200s.”

The setup they left behind was bleak: a handful of aging V100s and T4s in a local cluster, plus limited access to A100s and L40s on their university’s shared infrastructure, two at a time, if they were lucky. For anyone who’s tried to fine-tune a 30B parameter model on hardware from 2018, this is the academic equivalent of bringing a butter knife to a gun fight.

The Spark’s appeal wasn’t raw speed. It was having 128GB of unified memory sitting on a desk, no cloud queues, no begging for compute credits. Just a self-contained environment where experiments could run for days without someone else’s job preempting them.

Critics immediately pounced. The Spark’s GB10 chip delivers up to 1 petaflop of FP4 performance, but that’s theoretical. In practice, four RTX 3090s beat it on both price and performance for most workloads. The unified memory bandwidth caps at 273 GB/s, less than one-fifth of an RTX 5090’s 1.5 TB/s. For bandwidth-hungry inference, it’s objectively slower.

So why is this debate even happening?

The Memory Wall That Actually Matters

The Spark’s 128GB unified memory pool changes the game for foundation model experimentation in ways benchmark charts don’t capture.

Traditional GPU setups fragment memory. An RTX 4090 offers 24GB of VRAM. Run out? You need another card, another PCIe slot, another power cable. The memory pools stay separate, forcing constant data shuffling through PCIe at ~64 GB/s. For a 70B parameter model in FP16, you’re looking at 140GB just for the weights. Good luck with that on consumer hardware.

The Spark’s unified architecture lets models breathe. A 30B parameter model fits comfortably. A 70B model with quantization? Possible. For a small lab, this means actually loading the model without resorting to CPU offloading that grinds training to a halt.

But the real magic isn’t the memory size, it’s the coherence. CPU and GPU share a single address space over NVLink-C2C at ~900 GB/s. No explicit tensor.to("cuda") calls. No H2D/D2H transfers. The system behaves like one giant processor, which mirrors how NVIDIA’s data center systems work.

This is the first real taste of “real AI infrastructure” for researchers who’ve only known fragmented consumer GPUs and stingy university clusters.

The CUDA Trap Nobody Wants to Admit

Here’s where the controversy gets spicy. Multiple commenters identified the real strategy: NVIDIA isn’t selling a product, they’re building a pipeline.

The Spark ships with DGX OS, a tuned Linux distribution preloaded with CUDA, cuDNN, NCCL, TensorRT, and Triton. Everything just works. For a PhD student drowning in dependency hell, this is oxygen. For NVIDIA, it’s the first hit of a very addictive drug.

One commenter laid it bare: “Nvidia designed the Spark to hook up people like you on CUDA early and get you into the ecosystem at a relatively low cost for your university/institution. Once you’re in the ecosystem, the only way forward is with bigger clusters of more expensive GPUs.”

The numbers support this. The ConnectX-7 NIC alone, dual QSFP ports delivering 200Gb/s networking, costs ~$1,700 separately. NVIDIA includes it in a $3,999 box. Why? Because when your lab eventually needs to scale beyond one Spark, the only logical path is another Spark, then a DGX Station, then a DGX SuperPOD. All speaking the same language, running the same software stack, plugged into the same networking fabric.

This isn’t conspiracy theory. It’s textbook platform economics. The Spark is a loss leader for a $100,000 lifetime value customer.

Performance Reality Check: Where Spark Actually Shines

Let’s be brutally honest about performance. The Spark’s unified LPDDR5X memory at 273 GB/s is its Achilles’ heel for generation tasks. Benchmarks show it hitting 60-70 tokens/second on 20B models, usable, but a 5090 can double that.

Where it punches above its weight is prefill. The GB10 Blackwell chip’s compute capabilities deliver strong prompt processing performance, which matters more for research workflows involving long contexts and batch processing.

More importantly, the Spark runs workloads that simply won’t run on consumer hardware. Fine-tuning a 30B model with full parameter updates requires ~180GB of memory (weights + optimizer states + gradients). The Spark handles this. Four 3090s with 96GB total? Not a chance.

NVIDIA’s own benchmarks show fine-tuning throughput for Llama models that, while not matching H100 clusters, enables actual experimentation rather than theoretical paper calculations.

The Academic AI Arms Race

The real story here is democratization versus centralization. Foundation model research has become a gated community. The compute costs to even validate a new architecture idea are prohibitive. A single H100 costs $30,000. A cluster of 8? That’s a quarter million dollars before networking, storage, and power.

Small labs aren’t trying to train GPT-5. They’re trying to understand why Chain-of-Thought works, or how to make models more efficient, or whether a new attention mechanism has merit. These questions require running ablations on 7B to 30B models dozens of times with different hyperparameters.

The Spark puts this within reach. At $4,000, it’s still expensive, but it’s a departmental purchase, not a capital campaign. It lets researchers iterate locally, validate ideas, then burst to cloud for final scale-up.

This is the difference between participating in AI research and watching from the sidelines.

The Fine Print: What You’re Really Buying

The Spark is not a consumer product. It’s a development appliance. The value proposition includes:

- DGX Playbooks: Step-by-step guides for multi-agent systems, multimodal pipelines, quantization, and serving

- Direct NCCL support: Multi-node scaling that mirrors production clusters

- GPUDirect RDMA: Direct memory access from storage/network to GPU

- FP4/NVFP4 support: Next-generation quantization that consumer GPUs lack

These aren’t features. They’re training wheels for the NVIDIA ecosystem. When your startup gets funding and needs to scale, your team already knows the toolchain. When your lab wins a grant for a cluster, you spec DGX hardware because that’s what your workflow targets.

The controversy isn’t about performance. It’s about whether democratizing access to AI infrastructure is worth the cost of ecosystem lock-in.

Verdict: Overpriced or Overdue?

The DGX Spark is simultaneously overpriced and underpriced. For inference-only workloads compared to consumer GPUs, it’s poor value. For foundation model research in resource-constrained environments, it’s transformative.

The real competition isn’t the RTX 5090. It’s the status quo where small labs can’t run meaningful experiments. Against that benchmark, the Spark is a revolution wrapped in a gold chassis.

The controversy will persist because it forces a hard question: Should AI infrastructure be a utility, or a competitive advantage? NVIDIA is betting on the latter, and the Spark is their Trojan horse into academia.

For researchers choosing between watching the field evolve from the sidelines or buying into CUDA’s walled garden, the decision is surprisingly simple. The Spark isn’t perfect, but it exists. And right now, that’s enough.

Bottom line: If you’re a small lab doing foundation model research, the Spark isn’t just hardware, it’s a ticket to the conversation. Just know you’re paying for the ecosystem, not the FLOPs. And NVIDIA is betting that once you’re in, you’ll never leave.