Stretched Thin: China’s AI Engine Is Running on Fumes

The head of Alibaba’s Qwen team just said the quiet part out loud: Chinese AI companies are running on compute fumes. At the AGI-Next summit in Beijing, Justin Lin didn’t mince words about the resource canyon separating Chinese labs from their American counterparts. His assessment was blunt, less than a 20% chance of any Chinese company leapfrogging OpenAI or Anthropic with fundamental breakthroughs in the next three to five years.

That’s not the narrative you typically hear from Zhongguancun’s corridors, where recent IPOs for Zhipu AI and MiniMax raised over $1 billion and DeepSeek’s R1 model briefly made China look like a serious contender. But Lin’s comments expose a structural reality that marketing campaigns can’t paper over: the compute gap isn’t closing, it’s widening.

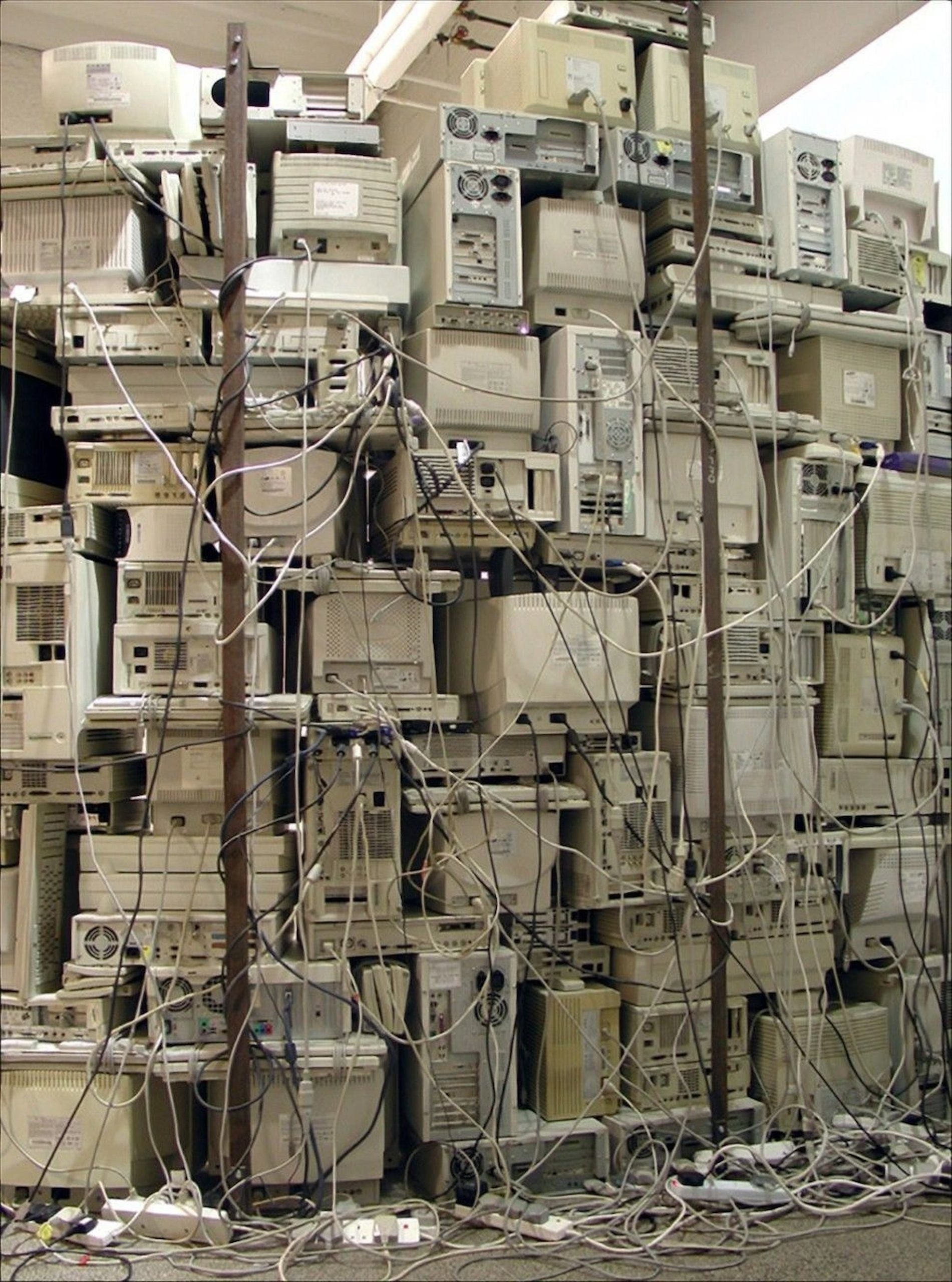

The Resource Disparity: Research vs. Survival

Lin’s most revealing comment cut through the usual diplomatic hedging: “A massive amount of OpenAI’s compute is dedicated to next-generation research, whereas we are stretched thin, just meeting delivery demands consumes most of our resources.” This isn’t just a budget allocation problem, it’s a fundamental misalignment of incentives.

The math is brutal. While OpenAI can dump thousands of H100s into training frontier models and exploring architectural breakthroughs, Chinese firms are stuck in a perpetual delivery sprint. Their limited GPU budgets get burned on fine-tuning models for commercial deployment, keeping existing customers happy, and scrambling to match last month’s benchmarks. The long-term research that produces actual breakthroughs? That gets whatever scraps are left.

This dynamic creates what’s essentially a research poverty trap. Without compute for experimentation, you can’t discover novel architectures or training methods. Without those discoveries, you can’t justify more investment. And without investment, you fall further behind in the hardware race.

Export Controls: The Invisible Firewall

The elephant in the room is U.S. export policy. Washington’s semiconductor restrictions have turned into a force multiplier for American AI dominance. Chinese firms can’t legally acquire Nvidia’s latest chips, forcing them into a gray market where they pay premiums for hardware that’s already one or two generations behind.

But the real damage isn’t just the hardware lag, it’s the uncertainty. As one analysis from Bernstein noted, while there’s a shortage of high-end training chips, local supply of less-powerful inference processors may actually exceed demand by 2028. This creates a bizarre bifurcation: Chinese companies might have plenty of silicon for running models, but precious little for training them.

The result? A generation of Chinese AI engineers who’ve become world-class at inference optimization while falling behind on training innovation. It’s like being a master of engine tuning while your competitors are building entirely new powertrains.

The Open-Source Paradox

Here’s where the story gets spicy. The breakout success of DeepSeek’s R1 model in early 2025 triggered a wave of open-sourcing among Chinese firms. Alibaba, Zhipu, and others rushed to release their latest models, and on paper, the gap with U.S. proprietary systems seemed to vanish overnight.

But Zhipu’s founder Tang Jie poured cold water on that narrative: “We just released some open-source models, and some might feel excited, thinking Chinese models have surpassed the US. But the real answer is that the gap may actually be widening.”

This is the open-source paradox in action. By giving away their best work, Chinese firms gain short-term prestige and developer adoption. But they also reveal their hand, allowing American labs to cherry-pick the best ideas while keeping their own breakthroughs locked behind APIs. It’s asymmetric warfare where one side publishes their battle plans and the other doesn’t.

Innovation Under Scarcity: Necessity or Fantasy?

The Reddit discussion around Lin’s comments revealed a sharp divide in how technologists view this constraint. The optimistic take, necessity is the mother of invention, suggests that compute starvation will force Chinese researchers to discover radically more efficient training methods. When the subsidy of abundant hardware disappears, you either get clever or you die.

There’s precedent for this. DeepSeek’s own research on hardware-efficient training got released publicly, showing that constraint-driven innovation is happening. The question is whether these optimizations can fundamentally alter the trajectory or just slow the inevitable.

The pessimistic view is more sobering: path dependence is real. As one technical analysis pointed out, you can’t just wish your way past mathematical constraints. Believing harder doesn’t make gradient descent converge faster. And while Chinese firms optimize their existing pipelines, American companies with superior hardware are exploring entirely new architectures that might make today’s efficiency tricks irrelevant.

The most cutting insight from the forums: Chinese firms have been trying to develop domestic chip parity for over a decade. By the time they catch up to today’s Nvidia GPUs, Apple, Google, and Nvidia will be several generations ahead. They don’t just need to hit a moving target, they need to predict where Western companies with already superior AI will be in 2030 and aim for that.

The Market vs. Reality Disconnect

The timing of Lin’s comments is instructive. He delivered this sobering assessment during a week when Chinese AI stocks were on fire. MiniMax doubled on debut. Zhipu climbed 36%. The market is pricing in victory while the engineers are measuring a growing gap.

This disconnect reveals a fundamental misalignment. Public markets reward shipping products and hitting revenue targets. They don’t reward long-term research bets that might pay off in five years, especially when you can’t even guarantee you’ll have the compute to run those experiments.

Tencent’s recent AI lead, Yao Shunyu (a former OpenAI researcher), is trying to thread this needle by focusing on “bottlenecks of next-generation models, such as long-term memory and self-learning.” But even this pragmatic approach requires compute for experimentation that may not have immediate commercial application.

The Efficiency Ceiling

Here’s what the cheerleaders miss: there’s a hard ceiling on how much efficiency can compensate for raw compute. You can only optimize so far before you hit fundamental limits. The “bitter lesson” of AI still applies, general methods that leverage massive compute beat clever, domain-specific hacks every time.

Chinese researchers are undoubtedly getting better at extracting performance from limited hardware. They’re probably doing world-class work on quantization, pruning, and distributed training. But these are incremental improvements in a game where the winners are making discontinuous leaps.

When OpenAI trains a model with a trillion parameters, they’re not just throwing hardware at the problem, they’re discovering emergent capabilities that only appear at scale. You can’t efficiency-hack your way to those insights. You need the actual flops.

The Geopolitical Implications

Lin’s rhetorical question, “does innovation happen in the hands of the rich, or the poor?”, has uncomfortable implications. Historically, necessity has driven invention. But in AI, the “rich” (well-resourced labs) are pulling away so fast that the “poor” might never catch up.

This isn’t just about corporate competition. It’s about AI sovereignty. If Chinese firms can’t independently develop frontier models, they’re permanently dependent on Western technology, either through licensing, stolen weights, or reverse-engineering APIs. That’s a national security non-starter for Beijing.

The likely response won’t be just more chip smuggling. Expect massive state investment in domestic semiconductor fabs, even if they’re economically irrational. Expect government-mandated consolidation of AI labs to concentrate scarce compute. And expect a wave of “good enough” AI solutions optimized for specific Chinese use cases where the government can control the deployment environment.

What This Means for Practitioners

-

Don’t bet on Chinese model parity anytime soon: If you’re building products that depend on frontier capabilities, plan on using U.S. models for the foreseeable future. The 20% probability Lin cited isn’t zero, but it’s not a foundation for strategic planning.

-

Watch for efficiency breakthroughs: The constraint-driven innovations coming out of China will be useful. Expect new quantization schemes, training optimizations, and inference tricks to percolate into open-source toolkits. These won’t close the capability gap, but they’ll lower deployment costs for everyone.

-

Compute is the moat: In a world where algorithms get open-sourced in months, sustained access to training compute is becoming the only durable advantage. This favors the hyper-scalers and puts pressure on startups to partner early or die.

-

Regulatory risk is asymmetric: U.S. export controls are effective. If you’re building AI infrastructure, understand that supply chain restrictions will likely tighten, not loosen. Plan for a bifurcated global market where Chinese and Western AI stacks diverge.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Lin’s comments weren’t a cry for help, they were a dose of reality. The Chinese AI ecosystem has made remarkable progress under constraints that would have crippled most industries. But there’s a difference between surviving and thriving, between optimizing and innovating.

The compute bottleneck isn’t just a temporary inconvenience. It’s a structural feature of the new AI geopolitics that will define the next decade. And as Lin’s 20% assessment suggests, the window for closing that gap is narrowing fast.

For all the hype about China’s AI ambitions, the engineers on the ground are making a simpler calculation: we’re running out of gas, and the next station is in hostile territory. That’s not a problem you solve with clever algorithms alone.