Z.ai’s IPO: The First LLM Company to Go Public Is Already Walking a Tightrope

Z.ai is about to become the world’s first pure-play LLM company to list on public markets, and the timing feels almost poetic. On January 8, the Chinese AI startup will debut on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, aiming to raise $560 million through an offering of 37.4 million shares at HK$116.20 each. For a company that emerged from Tsinghua University in 2019 and quickly joined China’s elite “AI Tiger” cohort, this should be a victory lap. Instead, it’s being met with a mixture of investor curiosity and developer dread, the kind of quiet anxiety that comes from watching a beloved open-source contributor put on a suit and tie.

The significance here is impossible to overstate. While tech giants like Google and Microsoft have folded LLMs into their existing empires, and while OpenAI remains stubbornly private, Z.ai is offering retail investors their first direct shot at owning a piece of a company whose entire existence is built on large language models. No cloud computing legacy. No advertising business to fall back on. Just the models, the talent, and the promise of artificial general intelligence. It’s either a bold new frontier or a high-wire act without a safety net, depending on who you ask.

The Offering: $560M on a Promise of AGI

Let’s start with the numbers, because they’re stark. Z.ai, currently operating as Knowledge Atlas Technology, is looking to raise HK$4.35 billion (roughly $560 million USD) in its debut. Chinese investment bank CICC is shepherding the offering, which values the company at a level that will be scrutinized heavily given the broader AI funding landscape. This isn’t just another tech IPO, it’s a test case for whether public markets are ready to price pure AI research companies.

The company has pedigree. Its GLM model family has attracted serious backing from China’s tech aristocracy: Alibaba, Tencent, Ant Group, Meituan, Xiaomi, and HongShan have all placed bets. A 2023 funding round brought in 2.5 billion yuan (~$350 million USD), giving Z.ai the resources to compete with better-funded American rivals. Their recent GLM 4.7 release briefly topped open-model leaderboards, showcasing particular strength in coding and complex reasoning, domains where technical users actually care about performance gains.

But here’s where the narrative gets complicated. Z.ai rebranded internationally in 2025, positioning itself as a global competitor to ChatGPT and Claude. Yet in January 2025, the U.S. Commerce Department added the company to its Entity List over national security concerns, potentially restricting access to American technologies. For a company whose mission is developing AGI “to benefit humanity”, being caught in geopolitical crossfire before even going public is a hell of a handicap.

The Open-Source Ticking Time Bomb

The real controversy isn’t the valuation or the geopolitics, it’s what happens to Z.ai’s open-source commitment once quarterly earnings reports enter the picture. Developer communities are already treating this IPO as the beginning of the end for open-weight releases, and the sentiment is more resignation than anger.

The pattern is familiar: a company releases powerful open models to build community goodwill and establish technical credibility, then gradually retreats behind API walls once the revenue pressure mounts. As one developer sentiment summarized it, “Everyone saying the Chinese open source was some gift to humanity was delusional. They did what they had to do to compete with larger companies with capital. Now that they got their foothold it’s business as usual.”

This cynicism isn’t unfounded. Z.ai’s handling of the GLM-4.6 “Air” release left a bad taste. The company initially hyped the model, gave release timelines, then went silent before eventually admitting it wasn’t coming. The sequence, overpromise, deny, obfuscate, retreat, looked less like a technical delay and more like a company learning how to manage community expectations like a corporate entity rather than an academic lab.

The core tension is simple: public markets demand predictable revenue growth, while open-source AI development is inherently unpredictable and often unprofitable in the short term. Z.ai currently offers subscriptions for $3/month, cheap enough for hobbyists but nowhere near enterprise ARR levels. The company also provides inference APIs and specialized services, but the question remains: can these revenue streams satisfy shareholders accustomed to SaaS margins?

Open Weights vs. Open Source: A Distinction With a Difference

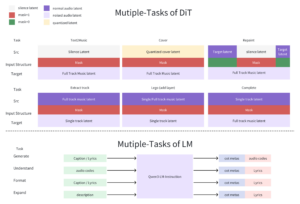

Much of the community anxiety stems from a semantic gap. What Z.ai and most “open-source” AI companies actually provide are open weights, model parameters you can download and run, but without the training data, full architecture details, or reproducible pipelines that define true open-source software.

As technical critics have pointed out, this is essentially “shareware models”, usable enough for free marketing, not quite good enough for production without significant finetuning. The pattern repeats: a small group releases an interesting model, it gets hyped on Reddit and Hacker News, then updates slow to a trickle as the team either gets acqui-hired or pivots to enterprise sales.

Z.ai’s GLM 4.7 is currently the best open model in the world by some benchmarks, but the community understands this leadership position is fragile. If Z.ai stops releasing weights, Minimax or another Chinese competitor can easily take their place. The actual cost of training these distilled models is vastly cheaper than what leading labs like OpenAI or Anthropic spend on frontier research. As one analysis put it, “If you aren’t SOTA closed source, I think it’s a better commercial option to be SOTA open source than crappy closed source. The cost of switching providers is too low.”

The Geopolitical Squeeze Play

The Entity List designation complicates Z.ai’s public market story in ways that go beyond typical IPO risk factors. Being cut off from certain U.S. technologies forces the company deeper into China’s domestic supply chain, which is both a strategic necessity and a commercial limitation.

On one hand, Chinese government policy still prioritizes AI self-sufficiency, which could mean continued support for open-source initiatives that strengthen the domestic ecosystem. On the other, public companies must navigate shareholder interests that may not align with state-level strategic goals. The $560M raise will need to fund not just research, but also domestic GPU procurement, software stack replacement, and compliance with both Chinese and international regulations.

This creates a paradox: Z.ai needs global investors to fund its AGI ambitions, but its geopolitical status makes it less attractive to Western capital. The Hong Kong listing is a compromise, access to international markets while staying within China’s regulatory orbit. Whether that balance is sustainable remains an open question.

Financial Reality Check

Here’s where the rubber meets the road. Z.ai hasn’t published detailed financials in the research provided, but the pattern among its peers is revealing. The Information’s analysis of IPO-bound AI model developers shows significant losses across the sector. These companies are burning cash on compute, talent, and inference subsidies while racing to build moats that may not exist.

The $560M raise sounds substantial, but in AI infrastructure terms, it’s modest. Training a single frontier model can cost hundreds of millions, and maintaining inference infrastructure at scale isn’t cheap. Z.ai’s bet is that it can thread the needle: keep releasing compelling open models to maintain community relevance, while building a profitable enterprise business that satisfies public market demands.

The problem is that enterprise buyers, the ones with actual budget, are increasingly choosing between:

1. Best-in-class closed models (GPT-4, Claude) for high-stakes applications

2. Self-hosted open weights for privacy-sensitive workloads

3. Cheap APIs from companies like Z.ai for everything else

That middle ground is crowded and compressing. If Z.ai can’t differentiate beyond price, its margins will suffer exactly when Wall Street starts asking tough questions.

What Happens Next

The IPO will likely succeed, there’s too much AI FOMO and too few pure-play options for it to flop completely. The real test comes in the subsequent quarters, when Z.ai must choose between competing masters.

- Scenario 1: The Mistral Path

Continue releasing open weights while building a premium enterprise tier. This satisfies the community but may not deliver the growth public markets expect. Mistral has managed this balance, but they’re European and face different geopolitical pressures. - Scenario 2: The OpenAI Pivot

Gradually close off the best models while maintaining a legacy open-weight line. This maximizes revenue but destroys the community goodwill that made Z.ai relevant. The GLM-4.6 Air debacle suggests they’re already practicing this pivot. - Scenario 3: The ByteDance Model

Go fully closed, focusing on consumer and enterprise products. This is the most shareholder-friendly path and the most community-hostile. Given Z.ai’s $3/month subscription model, this seems unlikely in the near term, but IPOs have a way of changing corporate DNA.

The Bottom Line

Z.ai’s IPO is a bellwether, but not in the way most coverage suggests. It’s not about whether AI companies can go public, they clearly can. It’s about whether the open-source AI ecosystem can survive contact with public market capitalism. The two models have fundamentally different incentive structures, and Z.ai is about to become the first major test of their compatibility.

For developers, the message is clear: enjoy GLM 4.7 while it lasts, but start building migration paths. For investors, the question isn’t whether Z.ai can build good models, they obviously can, but whether they can build a defensible business that doesn’t require choosing between community relevance and quarterly targets. For the AI industry, this IPO will either prove that open-source and public markets can coexist, or it will become the cautionary tale that every subsequent AI startup uses to justify staying private.

The $560M question is simple: when the earnings call starts, does AGI for humanity still matter, or does it become just another line item in the R&D budget that needs to show ROI?