Twilio Segment’s $3.2B Architecture Rebellion: Why They Killed Their Microservices

In 2018, Twilio Segment executed one of the most controversial architectural reversals in tech history: dismantling 140+ microservices and consolidating them into a single monolithic service. The move challenged a decade of microservices evangelism and exposed a harsh truth, what many call “microservices” is often just a distributed monolith with extra operational overhead.

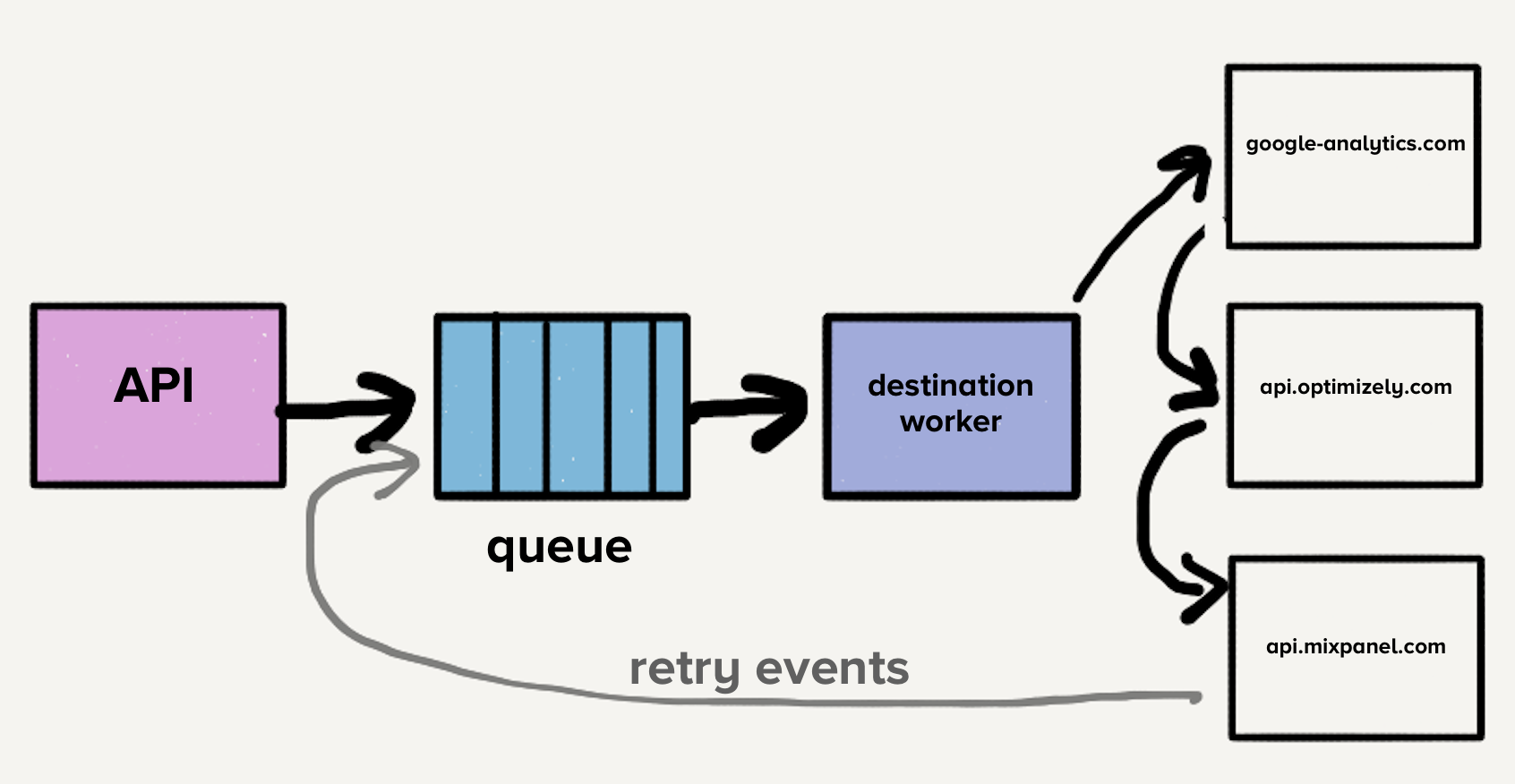

The story begins with a familiar scaling problem. Segment’s core product ingests hundreds of thousands of events per second and forwards them to partner APIs (Google Analytics, Optimizely, Mixpanel, etc.). Their initial architecture used a single queue, but head-of-line blocking meant one slow destination would delay all others. The solution seemed obvious: create a separate service and queue for each destination.

This microservice-style architecture isolated destinations from each other, exactly what textbooks recommend. For a while, it worked. But then the cracks appeared.

The Shared Library Trap

As destination count grew past 50, the team created shared libraries for common transforms and HTTP handling. This is where the microservices dream started curdling. Engineers would update libraries in one destination but not others. Version divergence became rampant. Eventually, all 140+ services ran different versions of shared libraries, creating a maintenance nightmare.

The real killer? When pressed for time, developers would only update libraries on a single destination’s codebase. This created a vicious cycle: the more destinations you had, the more expensive it became to keep libraries current. What started as a productivity boost became a tax on every change.

Testing compounded the pain. Each destination had tests that made real HTTP requests to partner endpoints. When credentials expired or services flaked, tests failed across unrelated destinations. The solution, separate repos, created a false sense of isolation. Failing tests became technical debt that no one wanted to clean up. A two-hour change could balloon into a week-long debugging slog.

The Operational Death Spiral

By the time they hit 140+ services, three full-time engineers spent most of their time just keeping the system alive. Auto-scaling became “more art than science” because each service had unique CPU and memory patterns. Low-traffic destinations required manual intervention during spikes. The on-call engineer regularly got paged at 3 AM for load issues.

The team was literally losing sleep over architectural choices that were supposed to make their lives easier. As one engineer later reflected, if you must deploy every service because of a library change, you don’t have services, you have a distributed monolith.

The Monolithic Resurrection

The reversal was methodical and brutal. First, they consolidated all 140 services into one. Then they merged 120+ unique dependencies into single versions, forcing everything onto the same page. The biggest innovation was Traffic Recorder, built on yakbak, which recorded and replayed HTTP traffic for tests. This eliminated flaky network dependencies and reduced full test suite time from an hour to milliseconds.

The results were stark:

– Deployment time: From hours coordinating 140+ services to minutes for a single deploy

– Library improvements: 46 improvements in one year versus 32 in the microservices era

– Operational load: A large worker pool absorbed traffic spikes, eliminating 3 AM pages

– Developer velocity: One engineer could deploy in minutes instead of teams spending days

The Controversy: Was It Ever Microservices?

This is where the industry debate gets heated. Critics argue Segment never implemented “true” microservices. The defining characteristic of microservices, independent deployability, was violated the moment shared libraries required coordinated updates. As one Hacker News commenter put it, “If you must deploy every service because of a library change, you don’t have services, you have a distributed monolith.”

The counterargument is more nuanced. Segment’s team was using different library versions precisely because they could deploy independently. The problem wasn’t lack of autonomy, it was the hidden cost of that autonomy. When a critical security patch hits, you can’t have 140 different versions of a logging library. The divergence that made independent deployment possible also made maintenance impossible.

The Organizational Reality Check

Conway’s Law looms large here. Segment’s team structure didn’t match their architecture. A small team building 140 services meant each engineer was effectively maintaining dozens of mini-applications. The cognitive load was crushing. As team size grows, microservices can help enforce boundaries between teams. But for a single team, those boundaries become self-imposed friction.

The real lesson isn’t “monoliths good, microservices bad.” It’s that architecture must match organizational reality. A three-person team can’t effectively own 140 services. The communication overhead that microservices are supposed to solve becomes a problem when you’re communicating with yourself across service boundaries.

The Metrics That Matter

The proof is in the productivity numbers. After the monolith migration, the team made 46 improvements to shared libraries in one year versus 32 in the microservices era. More tellingly, these improvements were actually deployed everywhere instead of living in dependency hell.

Operational metrics improved too. The monolith’s mixed workload profile meant CPU and memory resources balanced naturally. Instead of 140 different auto-scaling configurations, they had one. The large worker pool absorbed spikes that would have previously required manual intervention for low-traffic destinations.

The Trade-offs They Accepted

Segment’s engineers were clear-eyed about what they were giving up:

-

Fault isolation is difficult. A bug in one destination can crash the entire service. They’re working on stronger safeguards but accept the risk given their comprehensive test suite.

-

In-memory caching is less effective. With 3000+ processes, cache hit rates dropped. They accepted this efficiency loss for operational simplicity.

-

Dependency updates can break multiple destinations. But this was already true, the difference is now they know immediately instead of discovering version incompatibilities during production incidents.

The Industry’s Reflection

The Hacker News discussion reveals deep divisions. Some see this as validation that microservices were always overhyped. Others view it as a cautionary tale about nanoservices, services that are too small to justify their overhead.

The most insightful comments focus on the “distributed monolith” concept. Many companies implement microservices that are so tightly coupled through shared libraries, databases, or deployment coordination that they retain all the complexity of a monolith while adding network latency and failure modes.

What Actually Works

The evidence suggests neither pure monolith nor microservices is universally correct. Success depends on:

- Team size and structure: Microservices shine when teams need strong boundaries. Monoliths work when a small team needs maximum velocity.

- Domain boundaries: Services should align with business capabilities, not technical implementation details. One service per destination was too granular.

- Testing strategy: Record/replay testing was the real breakthrough, not the monolith itself. Flaky tests kill productivity regardless of architecture.

- Dependency management: Shared libraries create coupling. Either eliminate them or accept the cost of keeping versions synchronized.

The Bottom Line

Twilio Segment’s $3.2B acquisition by Twilio happened after this architectural reversal. The monolith didn’t sink the company, it may have helped save it. The team that couldn’t make headway with three engineers maintaining 140 services found they could move faster with one service and a robust test suite.

The controversy isn’t that they moved to a monolith. It’s that they had to. The microservices architecture they implemented was a textbook example of how good intentions can lead to a distributed monolith. The lesson isn’t to avoid microservices, it’s to recognize when your implementation has become the anti-pattern you’re trying to prevent.

For teams considering microservices, Segment’s story offers a clear warning: start with a monolith until organizational pain forces you to split. And if you do split, ensure your services are truly independent, not just technically, but operationally and organizationally. Otherwise, you’re not building microservices. You’re just building a very complicated monolith with network calls.