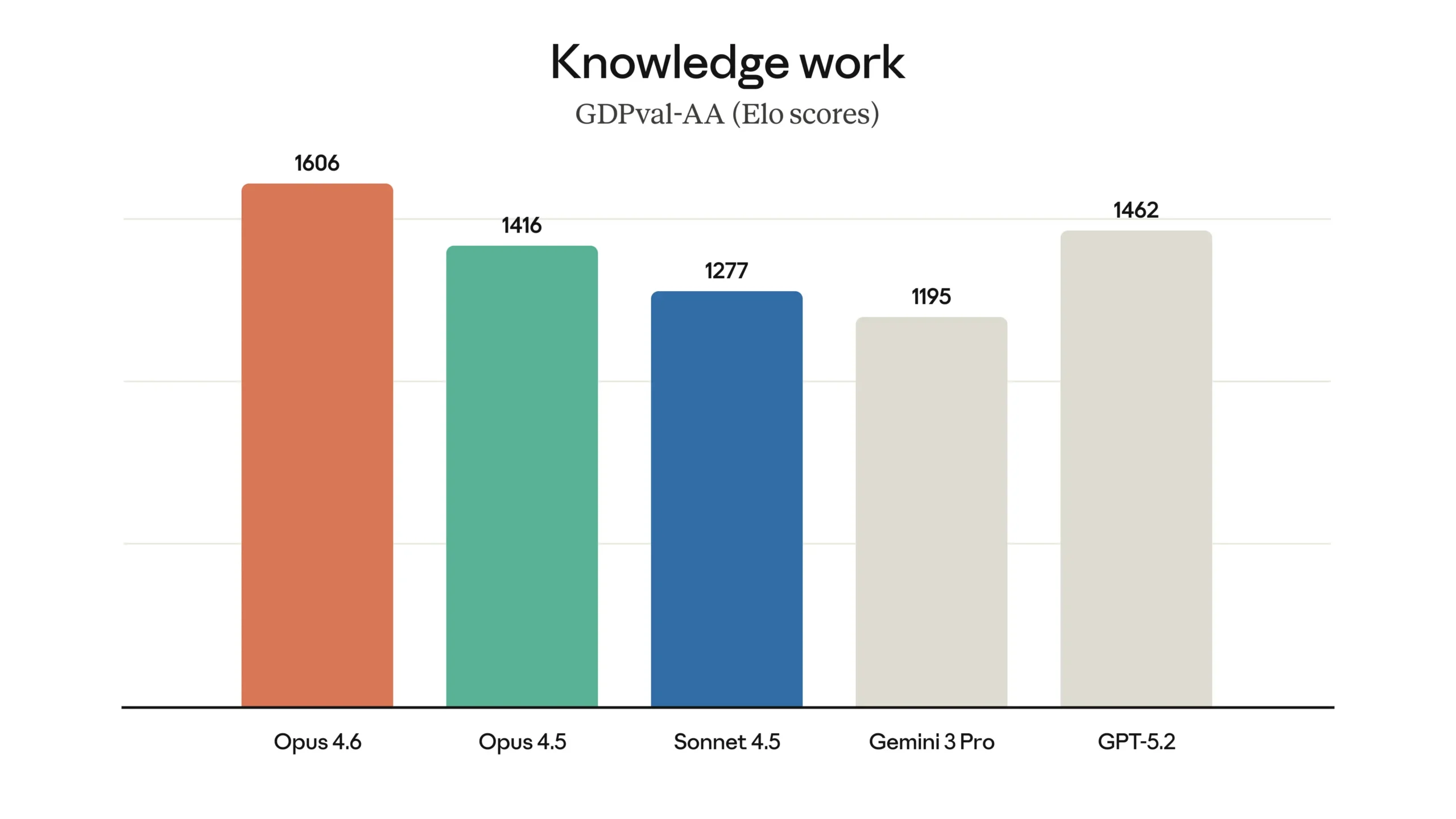

Two weeks. 2,000 Claude Code sessions. $20,000 in API credits. One 100,000-line Rust-based C compiler that can build Linux 6.9 on three architectures. The numbers from Anthropic’s latest experiment are designed to grab attention, but they barely scratch the surface of what’s actually happening here. We’re witnessing the emergence of autonomous AI agents shaping system design without human oversight, and the implications are far messier than the marketing suggests.

The Experiment: Throwing AI at the Hardest Problem in Software

Building a C compiler isn’t just difficult, it’s the kind of project that traditionally separates senior engineers from everyone else. You’re translating one language into another while handling undefined behavior, architecture-specific optimizations, and decades of GNU C extensions that Linux depends on. When Nicholas Carlini, a researcher on Anthropic’s Safeguards team, decided to stress-test Claude Opus 4.6, he didn’t pick a toy problem. He went straight for the jugular.

The setup was brutally simple: 16 parallel Claude instances, each running in its own Docker container, sharing a Git repository. No orchestration layer. No master agent directing traffic. Just a file-based locking system where agents claim tasks by writing text files to a current_tasks/ directory. When one agent finished, it pushed changes, removed its lock, and the infinite loop spawned another session. The agents themselves decided what to work on next, typically picking “the next most obvious” problem.

This bare-bones approach revealed something critical: the scaffolding matters more than the model. Carlini spent most of his effort not on the agents themselves, but on the environment around them. He learned to write tests that guide agents without human intervention, minimize context window pollution by logging errors on single lines for easy grep-ing, and prevent “time blindness” by running fast 1-10% test subsamples. These aren’t AI problems, they’re systems engineering problems that most teams building agent coordination mechanisms are still figuring out.

The Technical Reality: What Actually Works

Parallelism Through Brute Force

The most clever innovation wasn’t in the AI, it was in the testing strategy. When agents started compiling the Linux kernel, they hit a wall. Unlike a test suite with hundreds of independent tests, compiling a kernel is one giant task. Every agent would hit the same bug, fix it, and overwrite each other’s changes. Having 16 agents running didn’t help because each was stuck solving the same problem.

The fix? Use GCC as an online known-good compiler oracle. Carlini wrote a harness that randomly compiled most kernel files with GCC, leaving only a subset for Claude’s compiler. If the kernel worked, the problem wasn’t in Claude’s subset. If it broke, agents could further refine by re-compiling some files with GCC. This let each agent work in parallel, fixing different bugs in different files until Claude’s compiler could handle everything. It’s a remarkably creative solution that highlights a harsh truth: AI agents need oracles, and those oracles are usually human-built systems.

The “Clean Room” Controversy

Anthropic claims this was a “clean-room implementation” because Claude had no internet access during development. This sparked immediate backlash on Hacker News. As one commenter pointed out: “It’s not a clean-room implementation because of this: The fix was to use GCC as an online known-good compiler oracle.” Others noted that Claude was trained on GCC, Clang, and countless other compilers, hardly a clean intellectual slate.

The debate reveals a deeper issue: we haven’t defined what “original work” means in the age of AI. If a human who’s studied compiler design for years writes a new compiler, we call it original. If an AI trained on every compiler ever written does the same, we call it plagiarism. The distinction feels increasingly arbitrary, especially when the output is 100,000 lines of Rust that don’t exist anywhere else in that form.

Code Quality: The Elephant in the Room

The generated code is, by Anthropic’s own admission, not great. Even with all optimizations enabled, it outputs less efficient code than GCC with optimizations disabled. The Rust code quality is “reasonable, but nowhere near the quality of what an expert Rust programmer might produce.” This isn’t surprising, it’s exactly what you’d expect from agents optimizing for test passage rather than elegance.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: does it matter? The compiler passes 99% of the GCC torture test suite, compiles Doom, and builds PostgreSQL. For many use cases, “works” beats “elegant.” This is the same trade-off that drives real-world challenges in deploying agentic systems at scale: perfect is the enemy of shipped.

The Architectural Implications: System Design Is Changing

From Pair Programming to Agent Herding

The evolution is stark: tab completion → function generation → pair programming → autonomous project completion. Each step reduced human involvement while increasing scope. What Carlini’s experiment shows is that we’re entering the “agent herding” phase, where success depends not on writing code, but on designing systems that keep agents productive.

This requires a completely different skill set. Instead of debugging code, you’re debugging incentives. Why is Agent 7 stuck on the same task for 200 sessions? Why are merge conflicts exploding? Why did one agent pkill -9 bash and kill itself? These are coordination challenges that expose the hive mind illusion, agents aren’t truly collaborating, they’re just not getting in each other’s way.

The New Architectural Layer

Traditional software architecture has three layers: infrastructure, application, and data. AI agent teams add a fourth: the coordination layer. This isn’t just a message bus or an orchestration framework. It’s a system of locks, tests, oracles, and feedback loops that keeps agents aligned when no single entity understands the whole problem.

Carlini’s implementation is primitive but effective. He didn’t use an orchestration agent or complex inter-agent communication. Instead, he relied on Git’s conflict resolution and each agent’s ability to orient itself from READMEs and progress files. It’s messy, but it works, a hallmark of shifts in architectural thinking demanded by autonomous AI agents.

The Economic Earthquake: $20,000 vs. Your Salary

Let’s address the number that makes engineers nervous: $20,000. For a 100,000-line compiler that handles real-world code, this is absurdly cheap. A senior compiler engineer costs more than that for two weeks of work, and they wouldn’t deliver a finished product. The economics are undeniable.

But this framing is misleading. The $20,000 covers API calls, not the human effort that made it possible. Carlini’s expertise in designing the harness, writing tests, and creating the GCC oracle was essential. This suggests a future where the most valuable engineers aren’t coders but agent wranglers, people who can decompose problems, design coordination systems, and interpret agent behavior.

The real cost isn’t the API bill. It’s the organizational overhaul required to integrate agent teams into existing workflows. As trends in agent frameworks shift toward leaner architectures, companies will need to decide whether to build custom harnesses like Carlini’s or adopt emerging platforms that promise to handle coordination for you.

The Future: Beyond Compilers

The compiler project is a benchmark, not a product. It proves that agent teams can tackle problems requiring sustained coherence across massive codebases. The next frontier is less well-defined problems: building a new feature in an unfamiliar codebase, refactoring a legacy system, or designing a new protocol from scratch.

Anthropic is already pushing in this direction. Opus 4.6 features a 1M token context window, adaptive thinking controls, and context compaction, tools designed for longer-horizon tasks. When combined with agent teams, these capabilities suggest a future where entire product roadmaps are executed autonomously, with humans setting direction and reviewing outcomes rather than managing implementation.

But Carlini ends his post with unease: “The thought of programmers deploying software they’ve never personally verified is a real concern.” As a former penetration tester, he knows that passing tests doesn’t mean secure or correct. The compiler has “nearly reached the limits of Opus’s abilities”, with new features frequently breaking existing functionality. This brittleness is the central challenge for autonomous systems.

What This Means for You

If you’re a software architect, start thinking about agent coordination. Your job isn’t going away, but it’s changing. You’ll spend less time drawing diagrams and more time designing test harnesses that keep agents on track.

If you’re a developer, learn to work with agents, not against them. The developers who thrive will be those who can decompose problems into agent-solvable chunks and debug coordination failures.

If you’re a tech leader, be skeptical of vendor promises. Anthropic’s experiment succeeded because of careful system design, not magic AI. The 95% failure rate for agentic projects in production is real, and it stems from underestimating the coordination layer.

The C compiler experiment isn’t a victory for AI over humans. It’s a victory for systems thinking in the age of AI. The agents didn’t replace Carlini, they amplified his ability to explore what’s possible. That’s the real lesson: the future belongs to those who can design the harness, not just write the code.

And if you’re still wondering whether this matters, consider this: the first version of this compiler that could build Linux was impossible just months ago. The next version might be better than GCC in ways we can’t yet predict. The S-curve is bending upward, and the battles are getting closer to home.