The software architecture industry has been running a 30-year con. We’ve been sold a bill of goods: pattern catalogs as the “ubiquitous language” of software design, vessels of shared experience, construction sets for engineering. The reality? Over 2,000 patterns, no human can remember them all, names so ambiguous that “Front Controller” means three different things, and the same ideas reinvented every decade with fresh jargon to sell books.

Enter what might be the most incendiary idea in recent software architecture: The Geometric Theory of Architecture. It doesn’t just challenge the pattern catalog industrial complex, it threatens to make it obsolete. The thesis is disarmingly simple: Structure determines function, there are only so many elementary geometries, and hundreds of patterns condense into a handful of metapatterns.

If you’re emotionally attached to your copy of “Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture”, you might want to stop reading now.

The Pattern Catalog Crisis No One Wants to Admit

Let’s start with the dirty secret that pattern enthusiasts won’t discuss. The SpeakerDeck presentations for the book Architectural Metapatterns lay out the problem with surgical precision: we were promised a pattern language that would unify software engineering. What we got is a tower of babel.

Consider the “Front Controller.” In one authoritative source, it’s a service that tracks request status from a pipeline. In another, it’s a backend MVC component parsing client requests. Same name, completely different structures, properties, and use cases. This isn’t an isolated case, it’s the norm.

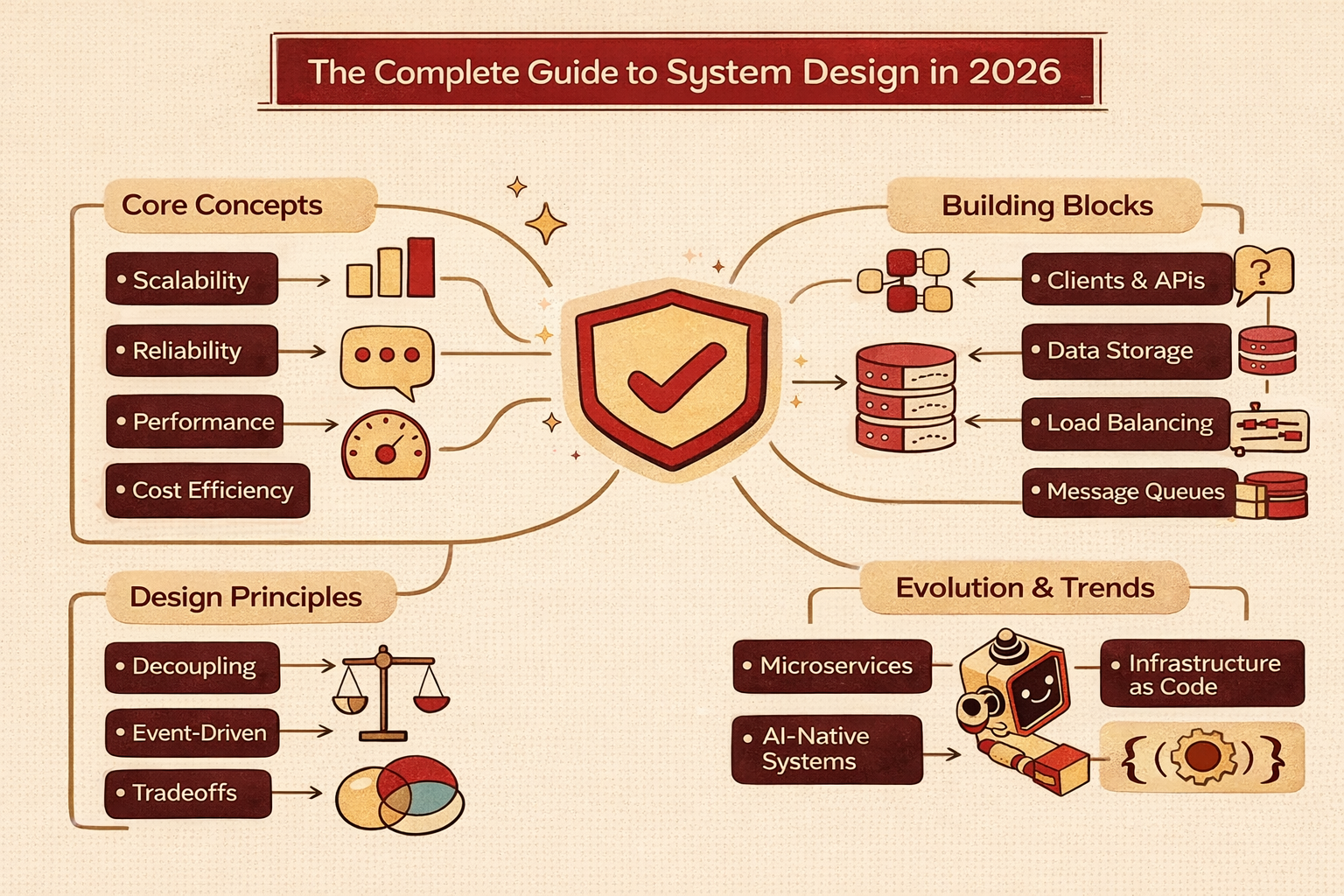

The research reveals something worse than ambiguity: plagiarism masquerading as innovation. Compare Hexagonal Architecture (2005) with Model-View-Controller (1979). Both isolate core logic from external components. Both support multiple views/platforms. Both protect against vendor lock-in. The structural similarity is undeniable, yet we treat them as distinct intellectual contributions. The same applies to Ports and Adapters, Onion Architecture, and Clean Architecture, architectural triplets separated only by their birth years and authors’ speaking fees.

The pattern catalog promised continuity of knowledge. Instead, it delivered ritualistic renaming, breaking the chain of experience and preventing cross-domain knowledge sharing. We’ve been documenting the same five shapes for three decades, each time claiming we’ve discovered fire.

The Geometric Revelation: Structure Determines Function

The breakthrough insight from the metapatterns research is that local and distributed architectures are not fundamentally dissimilar. Once you segregate the properties that only exist because of distribution (network latency, partial failure, independent scalability), what remains is structurally identical to decades-old local patterns.

This is where the geometric theory gets spicy. The researchers mapped architectures using a common coordinate system with three axes:

– Abstractness: How far a component is from concrete implementation

– Subdomain: How components align with business domains

– Sharding: How instances partition data and work

Plot any architecture in this 3D space, and its geometry reveals its function. A component’s position along these axes determines its scalability, fault tolerance, development team structure, and technological constraints. Structure determines function, not the other way around.

This isn’t metaphorical. It’s mathematical. And it means there are only so many distinct geometries before you start drawing the same shapes with different labels.

The Five Elementary Forms

Here’s where the theory becomes actionable, and heretical. The research identifies five basic metapatterns that serve as the elementary particles of software architecture:

1. Monolith: The Cohesive Stone

A monolith is a cohesive (sub)system that cannot (or should not) be subdivided. In its strict sense, it’s a single codebase. In practice, it’s what happens when you don’t want to look inside something because it’s either trivial or terrifying.

Trade-offs are brutal: easy to write and debug, low latency, thorough optimization potential, but hard to read, doesn’t scale, zero fault tolerance, and developed by a single team. The research notes that “Monolith” has been redefined several times, with the latest version being “a single unit of deployment”, a semantic drift that proves the theory. We’re so desperate to avoid admitting we’re building monoliths that we rename them “modular monoliths” or “distributed monoliths” (which is just SOA with extra guilt).

2. Shards: Parallel Universes

Shards are multiple instances of a component that may differ in data but don’t intercommunicate directly. This geometry provides scalability and fault tolerance as long as there is no shared data, the architectural equivalent of “don’t talk to each other and everything will be fine.

The sharding geometry appears everywhere: thread-per-shard (limited scalability), process-per-shard (software fault tolerance), server-per-shard (full scalability). Partitions own slices of data, replicas own copies of all data. Stateless instances with a shared repository (like Lambdas) push the geometry to its logical extreme: perfectly scalable compute, but the shared repository becomes your bottleneck and single point of failure.

3. Layers: The Abstraction Stack

Layers subdivide systems by abstractness, upper layers depend on lower ones, but not vice versa. This is the classic 3-tier architecture (frontend/backend/database) or DDD’s presentation/application/domain/infrastructure stack.

The geometry is clear: each layer may be developed by a dedicated team, differ in technologies, scalability, and even physical location. But the interfaces between layers negatively impact performance, and the number of practical layers rarely exceeds 3-4 before communication overhead drowns you. Tiers are just distributed layers, proving the local/distributed convergence thesis.

4. Services: Subdomain Islands

Services align components with business subdomains. When subdomains are loosely coupled, services enable multi-team development with minimal communication overhead. This is the geometry behind microservices, service-based architecture, and actors.

The research is blunt about the cost: use cases involving multiple subdomains become slow and complicated, subdomain boundaries must never change (good luck with that), and state synchronization is a nightmare. You’re trading development speed for operational complexity and latency. The geometry doesn’t care about your domain-driven design purity, it dictates these consequences.

5. Pipeline: The Assembly Line

A pipeline passes data through a chain of processing steps. It’s services with unidirectional data flow, specialized for stream processing but inflexible for integration logic. Pipes and Filters, Event-Driven Architecture, and Data Mesh all share this geometry.

The pattern is ancient, yet we keep rebranding it. Choreographed Event-Driven Architecture is just a distributed pipeline with fancier error handling. Data Mesh is a pipeline graph for analytical data. The geometry remains identical, only the jargon evolves.

The Controversial Coordinate System

What makes this theory genuinely radical is the 3D classification system. Traditional pattern catalogs are flat, lists of names and definitions. The geometric theory says: plot your architecture in abstractness-subdomain-sharding space, and its properties become predictable.

This is why Hexagonal Architecture and MVC are the same shape, they occupy identical coordinates in this space. The “innovation” was moving from 2D to 3D thinking, not discovering a new geometry. The research shows that once you segregate distribution-specific properties (like independent hardware scaling), distributed tiers become structurally identical to local layers.

This is the unified field theory of software architecture. It explains why OS drivers and microservices share geometry despite different domains and scales. It reveals that Event-Driven Architecture and Pipes-and-Filters are the same shape, just distributed differently.

Beyond the Pentad: Extension and Fragmentation

The five basic metapatterns combine and extend to create what the research calls extension metapatterns (Middleware, Shared Repository, Proxy, Orchestrator, Combined Component) and fragmented metapatterns (Layered Services, Polyglot Persistence, Backends for Frontends, SOA, Hierarchy).

But here’s the kicker: these aren’t new geometries. They’re compositions of the five elementary forms. Service-Oriented Architecture isn’t a sixth shape, it’s Layers composed of Services. CQRS is Services with specialized read/write geometries. Microkernel is Monolith-with-Plugins with a specific resource mediation geometry.

The hierarchy pattern is particularly revealing: it’s recursive subdivision using the same five shapes at different scales. A top-down hierarchy is orchestrators-of-orchestrators (Pipeline + Services). A bottom-up hierarchy is bus-of-buses (Pipeline + Middleware). The WSO2 Cell-Based Architecture is just Services that behave like Monoliths at a larger scale.

Why This Theory Burns Everything Down

The geometric theory isn’t just academic, it’s a direct assault on how we teach, sell, and certify software architecture. If true, it means:

- Pattern books are mostly redundant: You’re paying for five shapes with 2,000 different names.

- Architecture certification is memorization theater: Understanding five geometries is more valuable than memorizing 200 pattern definitions.

- “Best practices” are often geometric confusion: Using microservices when you need shards is forcing the wrong geometry on your problem.

- Innovation is mostly rebranding: The “new” architectures of 2025 are the same shapes as 1975, just plotted at different coordinates.

The research acknowledges limitations: the structural approach works only for system-wide architectural patterns, not GoF design patterns or Enterprise Integration Patterns. But within its domain, it’s devastating.

The Real-World Validation

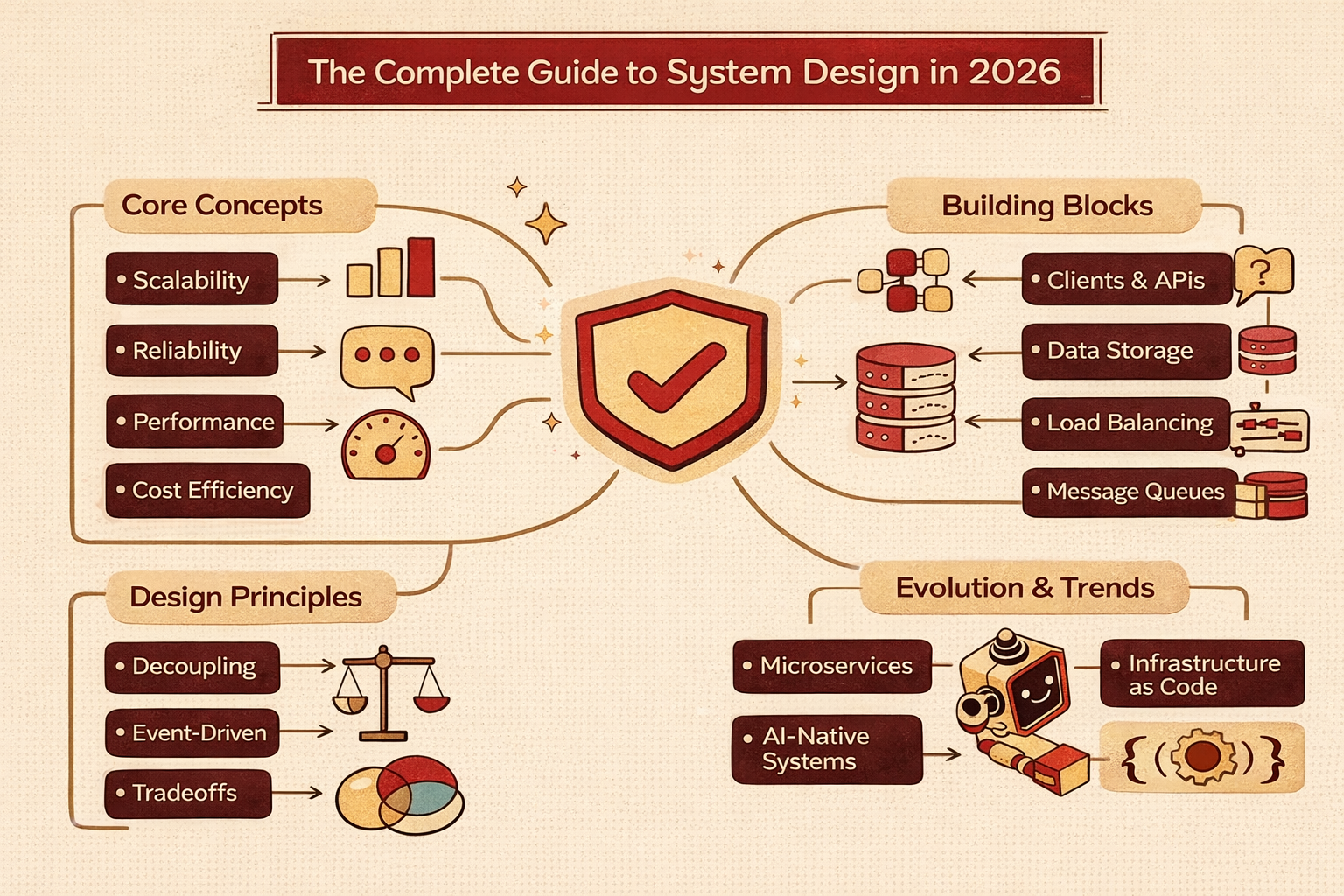

The theory survives contact with reality. The evolution of system design shows the same geometric patterns repeating:

- Monoliths → Shards (horizontal scaling)

- Layers → Services (team autonomy)

- Pipeline → Event-Driven (distributed processing)

Each step is a geometric transformation along one axis of the coordinate system, not a new pattern discovery.

Even modern “serverless” architectures are just stateless shards with a shared repository, two elementary geometries combined. The innovation wasn’t the shape, it was the managed infrastructure that made that geometry economically viable.

The Implications for Practitioners

If the geometric theory holds, your architecture strategy changes dramatically:

Stop pattern shopping: You don’t need to evaluate 50 patterns. You need to understand where your problem sits in the 3D coordinate space and which of the five geometries fits.

Embrace composition: Complex architectures should be composed from the five basic forms, not selected from a catalog. If you can’t decompose your design into Monolith, Shards, Layers, Services, and Pipeline, you don’t understand it.

Question “new” patterns: When someone pitches a revolutionary architecture, plot its geometry. Is it genuinely new, or just a basic metapattern at a different coordinate?

Design for transformation: The coordinate system suggests architectures can be morphed along axes. A monolith can become sharded. Layers can become services. Understanding the geometric transformations is more valuable than memorizing pattern names.

The Verdict: Heresy or Holy Grail?

The geometric theory of architecture is either the most important reframing of software design in decades or elegant nonsense. Its strength is its predictive power: plot the geometry, know the properties. Its weakness is its reductionism: real-world constraints often force hybrid shapes that defy clean classification.

But even if the theory is only partially true, it exposes an uncomfortable reality: we’ve been complicating software architecture to create an industry. The pattern catalog business, certification schemes, and conference circuits depend on the illusion of endless novelty. The geometric theory suggests it’s mostly theater.

The research is early-phase and not organizationally supported (read: no corporate sponsor wants this message). But it’s available at metapatterns.io and Leanpub, with diagrams under CC BY license. The author essentially dares the community to prove it wrong or make it recognized.

Whether you accept the geometric theory or not, it forces a necessary question: Do we need 2,000 patterns, or just better tools to compose five? The answer will determine whether software architecture matures into a true engineering discipline or remains a collection of tribal folklore.

The pattern catalog industrial complex won’t go quietly. But then again, neither did Ptolemy’s epicycles.