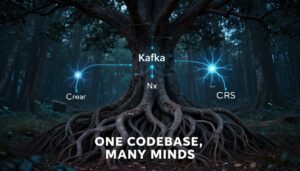

A mid-sized tech company is burning $15,000 every month on a Kafka setup that processes a modest 500GB of daily data. The original architect left two years ago, leaving behind a massively overbuilt system designed for growth that never materialized. When an engineer tries to raise the issue, the response is always the same: “What if we need that capacity later?”

This isn’t a hypothetical. It’s a real scenario playing out across engineering teams right now, and it reveals a brutal truth about infrastructure costs: the biggest line item isn’t always the most rational one. It’s often the one everyone is too terrified to challenge.

The Math That Should Make You Angry

Let’s start with the numbers from that Reddit post that sparked this conversation. Fifteen thousand dollars per month translates to $180,000 annually. For context, that’s more than the fully-loaded cost of a senior software engineer in most markets. The system in question handles roughly 500GB of data daily, seriously modest volume in an era where teams routinely process terabytes per hour.

The overprovisioning is almost comical: 30-day retention policies when most data gets consumed within hours, server counts that assume hockey-stick growth that never arrived, and capacity planning based on fear rather than telemetry. When the engineering team finally implemented Gravitee for visibility, it confirmed what they suspected: the cluster was a ghost town of idle resources and wasted potential.

But here’s where it gets politically interesting. As one commenter bluntly stated, cost of time and salaries often dwarfs infrastructure spend. The argument goes: why risk hundreds of engineering hours refactoring a working system to save $10,000 monthly? It’s a seductive piece of logic that has killed more cost-optimization initiatives than any technical hurdle.

Organizational Inertia as a Line Item

The real villain isn’t Kafka, it’s the institutional cowardice that forms around any system labeled “mission-critical.” Once a platform like Kafka crosses that threshold, it becomes untouchable. Engineers who propose changes face a gauntlet of risk-averse questioning: What if something breaks? What if we need that headroom? What if you’re wrong?

This creates a perverse incentive structure. The engineer who keeps their head down and lets the cluster hemorrhage money faces zero career risk. The engineer who attempts optimization and causes a single outage, even a minor one, gets labeled as reckless. As one tech director in the Reddit thread noted, they’ve fired people for unauthorized refactors that introduced bugs into working systems. The message is clear: stability trumps efficiency, even when that “stability” is just a slow-motion fiscal disaster.

The irony? The same organizations that balk at a $50,000 refactoring project will happily pay $180,000 annually for five years running. That’s nearly a million dollars in waste, but it’s invisible waste, no single invoice triggers alarm bells, and no single person owns the decision to keep paying it.

The Overprovisioning Epidemic

What makes this Kafka crisis particularly acute is how easily it spreads. Start with a simple use case, sending notifications between services, and before you know it, you’ve got a “massive thing nobody wants to touch.” The original architect’s optimism about future scale becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: the system is so complex and brittle that any attempt to right-size it feels like defusing a bomb.

The data tells a damning story. The company bus architecture described in streaming media case studies shows teams taking shortcuts because “using Kafka properly requires additional infrastructure.” Instead of building that infrastructure, they expose internal state directly to the bus, a recognized antipattern that creates downstream chaos. This technical debt compounds until the system becomes a black box of dependencies and workarounds.

And when teams do try to measure the waste? They face another organizational wall. As one Reddit commenter demanded: “Why should the business care to prioritize this? And no, ‘it costs $15k’ is not a sufficient answer.” This reveals the communication gap between engineering and leadership. Engineers lead with technical metrics, executives want business impact. Until someone translates “$15k monthly waste” into “this is costing us a senior engineer’s salary”, the checks keep getting written.

When “Good Enough” Becomes a Strategic Threat

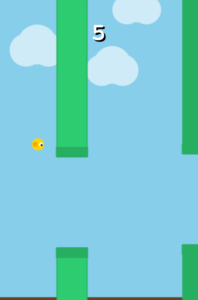

The most dangerous moment is when the overprovisioned system actually works well enough. It’s reliable. It’s manageable. It’s a known quantity. These are the exact words used to defend the status quo. But this reliability is a mirage built on exponential cost curves and stifled innovation.

Consider the opportunity cost. Every dollar spent on idle Kafka capacity is a dollar not spent on features that could differentiate the product. Every hour engineers spend maintaining this oversized beast is an hour not spent on higher-value problems. The technical director in that Reddit thread had it right: time is finite, and refactoring a working system sits at the bottom of the priority list, until it doesn’t.

The diskless Kafka proposals emerging from the community (KIP-1150, KIP-1176, KIP-1183) highlight just how much cost could be eliminated. By leveraging object storage and eliminating cross-AZ replication overhead, organizations could slash infrastructure spend by 40-60%. But these innovations require something most companies lack: the organizational will to change a working system.

Breaking the Cycle: From Fear to Fiscal Sanity

So how do you kill a $180,000/year zombie cluster? Not with a technical proposal. Not with a Jira ticket. You do it with a business case that makes the cost of inaction impossible to ignore.

Step one: weaponize visibility. The Gravitee implementation is a perfect example. You can’t argue with utilization metrics that show 90% idle capacity. Make the waste visible in dashboards that executives actually see.

Step two: reframe the savings. Don’t say “we can reduce broker count by 60%.” Say “we can fund two additional product engineers by optimizing our data infrastructure.” Speak the language of business outcomes, not technical efficiency.

Step three: start with a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. The cell-based architecture approach from streaming infrastructure case studies shows how to reduce blast radius without a full rewrite. Split traffic by country, by user tier, by platform. Create parallel paths where you can test optimization safely.

Step four: address the human debt. Technical debt is often a symptom of human debt, lack of skills, turnover, or poor leadership. The Reddit thread’s most upvoted comment asked about $15k as a percentage of overall infrastructure and revenue. This is the right question. It forces a conversation about proportionality and risk tolerance.

The Controversial Truth

Here’s the spicy take that gets engineers nodding and managers uncomfortable: overprovisioned Kafka clusters are not a technical problem. They are a governance failure. They represent a breakdown in how organizations make decisions about resource allocation, risk management, and technical ownership.

The engineers who built these systems are often long gone. The people paying the bills don’t understand what they’re paying for. And the people who understand the problem lack the political capital to fix it. This creates a perfect storm of waste where the only winners are cloud providers billing by the hour.

The path forward requires rethinking how we fund and govern infrastructure. Instead of treating it as a sunk cost, we need to treat it as a strategic asset that requires active management. This means dedicating real engineering time to optimization, not as a side project, but as a core responsibility. It means creating incentives for efficiency, not just uptime. And it means having the courage to touch systems that work, even when it’s politically risky.

Because the real cost of “it works” isn’t just the $180,000 annual invoice. It’s the innovation you didn’t fund, the talent you frustrated, and the competitive edge you dulled while paying for capacity you never needed.

The question isn’t whether you can afford to optimize your Kafka cluster. It’s whether you can afford not to.