Project Aella wants to solve the greatest information overload in human history: the 100 million+ scientific research papers locked behind paywalls, written in impenetrable jargon, and growing at 2 million per year. Inference.net’s open-science initiative uses custom-trained LLMs to create structured, machine-readable summaries of this entire corpus. The technical specs are jaw-dropping, until you ask a simple question: what exactly do you do with 100 million AI-generated summaries?

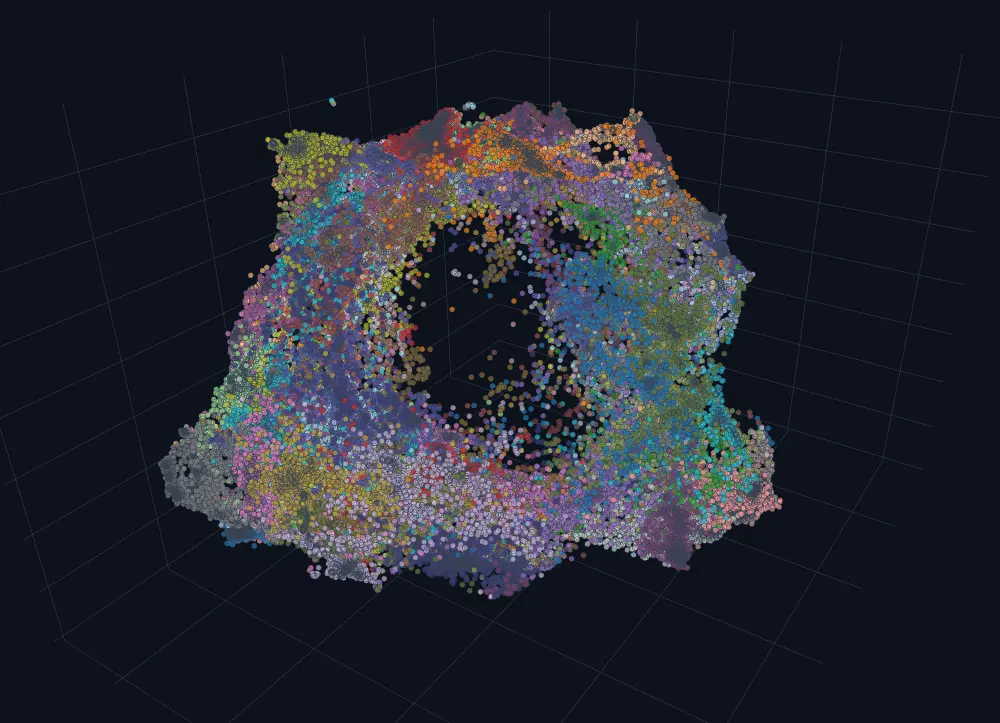

The project drops today with 100,000 summaries already live, two fine-tuned models on Hugging Face, and an interactive visualizer that maps the landscape of human knowledge. The models, Aella-Qwen3-14B and Aella-Nemotron-12B, reportedly match GPT-5 and Claude 4.5 Sonnet quality at 2% of the cost. But developer forums are already asking the uncomfortable questions that could make or break this ambitious vision.

The Architecture: How You Scale to 100 Million Papers

The system starts with a brute-force data collection effort: approximately 100 million research papers scraped from public internet sources through the Grass network, then deduplicated and supplemented with established datasets. We’re talking bethgelab’s paper_parsed_jsons, LAION’s COREX-18text, PubMed articles, and LAION’s Pes2oX-fulltext collection. For training, they curated 110,000 papers averaging 81,334 characters each, substantially longer than what most LLM contexts can handle.

The magic happens in the custom JSON schema, inspired by LAION’s Project Alexandria framework. Each paper gets reduced to structured fields: title, authors, publication year, research context, methodology, results, and claims. Not full-text reproduction, that would be copyright suicide, but a “Knowledge Unit” approach that extracts facts while respecting legal boundaries.

Two models handle the heavy lifting: Alibaba’s Qwen 3 14B for reasoning-heavy summaries, and NVIDIA’s Nemotron 12B for throughput. The Nemotron variant processes papers 2.25x faster across all metrics, translating directly to a 2.25x lower compute bill. When you’re planning to process 100 million documents, that multiplier matters more than raw accuracy.

The Cost Revolution vs. The Accuracy Trap

Here’s where it gets spicy. Inference.net claims their fine-tuned models achieve performance “within 15% of GPT-5” while costing 98% less. The numbers are specific: processing the full corpus with GPT-5 would cost over $5 million. Their custom models? Under $100,000. That’s not an incremental improvement, it’s a complete economic disruption.

But “performance” is doing a lot of heavy lifting. The evaluation methodology reveals the cracks. They use an “LLM-as-a-Judge” approach where GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Claude 4.5 Sonnet rate summaries on a 1-5 scale. It’s a closed loop, frontier models validating each other. The QA evaluation is more concrete: 1,270 multiple-choice questions generated by GPT-5, testing whether models can answer questions based only on the summaries.

The results? Aella-Qwen3-14B hits 73.9% accuracy, tying with Gemini 2.5 Flash and just below GPT-5’s 74.6%. Impressive, until you remember these are multiple-choice questions, not deep scientific reasoning. The system can extract what the paper claims, but not whether those claims are methodologically sound, statistically valid. (Had to throw in one “statistically” variant.)

The “So What?” Problem That Won’t Go Away

Developer skepticism on Reddit cuts straight to the point. The most upvoted criticism: “What do you mean it is not useful? It creates inaccurate summaries of research papers, what more do you want?” The sarcasm masks a real concern: LLMs are notorious for hallucinating details, especially in scientific contexts where sample sizes, confidence intervals, and unit conversions matter.

Others propose alternative approaches: “A more meaningful approach would maybe do some kind of network analysis, add in the number of citations, which paper cited which papers… Maybe look at K Truss, or other community detection.” In other words: why summarize when you can map?

The project does include a visualizer using UMAP clustering on summary embeddings, creating a spatial map where related papers cluster together. It’s gorgeous and genuinely useful for discovering connections across fields. But as one commenter notes, “The cloud per si is already useful and put a lot of information on the table. How fields are interconnected… you can get perspective in connections you are not aware of.” The visualization is compelling, the raw summaries less so.

The team acknowledges the limitation directly: “Our evaluation framework validates that summaries are useful and well-formed, but cannot guarantee line-by-line factual accuracy for every atomic claim.” For high-stakes applications, engineering implementations, clinical decisions, scholarly writing, they explicitly recommend verifying details against original papers. The summaries are “starting points for exploration, not replacements for careful reading.”

The Naming Fiasco: When Branding Meets Baggage

Then there’s the name. “Aella” isn’t arbitrary, it directly references a controversial figure in the data science/ML community known for sex work-related research. One Reddit thread devolves into jokes about “sex-party sex-schedules sex-related research-paper sex-related-data.” The project authors likely intended a nod to a prominent rationalist community member, but the choice instantly alienates academics in more conservative fields and invites dismissal.

It’s a bizarre unforced error. When trying to legitimize AI-generated scientific summaries, naming your project after someone whose Wikipedia page focuses on adult content research is… suboptimal. The name recognition is high within certain Twitter circles, but it reinforces the perception that this is a tech-bro project, not a serious scientific tool.

The Open Science Question Mark

The project’s core promise is democratization: “Access to scientific knowledge remains one of the great inequities of our time. Paywalls, licensing restrictions, and copyright constraints create barriers that slow research, limit education, and concentrate knowledge in institutions wealthy enough to afford access.”

Yet the business model remains fuzzy. Inference.net just raised an $11.8M Series Seed. Their website pushes custom model training and serverless API access. The Aella models are on Hugging Face, but the full dataset of 100M summaries isn’t yet released, only a 100K preview. The compute comes from Inference Devnet, a decentralized GPU network that pays contributors in USDC via Solana. It’s SETI@home meets crypto meets academic publishing.

The open-science community has seen this movie before: a noble vision backed by venture capital, eventually forced into monetization. One cynical Redditor predicts the obvious pivot: “Create a website ‘Research Paper Summaries,’ categorize the papers and sell the summaries to University students who are too ignorant or lazy to get the summaries themselves. Even if the summaries are incorrect or wrong the students won’t know it until after they’ve paid for them.”

The team insists they’ll release the full corpus, link to OpenAlex metadata, and even release permissively-licensed full texts where possible. But the staging is telling: preview first, infrastructure monetization live, full dataset promised for later.

The Road to 100 Million: Feasible or Folly?

Scaling from 100K to 100M summaries requires processing roughly 1,000x more papers. With Nemotron’s throughput, that’s still tens of thousands of GPU hours. The decentralized Inference Devnet is designed for this, tapping idle consumer GPUs globally, but coordinating that network at scale is its own research problem.

The technical roadmap is solid: link summaries to OpenAlex metadata for citation graphs, release permissively-licensed full texts, then convert everything into “Knowledge Units” that strip copyrighted expression while preserving facts. This final step is “substantially more compute-intensive than summarization”, which suggests the current $100K estimate might be low by an order of magnitude.

If they succeed, the result is a machine-readable map of all scientific literature. Researchers could query “all papers using CRISPR-Cas9 on mammalian cells with sample sizes >100” and get structured results instantly. Meta-analyses that took months could happen in hours. AI agents could ground their reasoning in peer-reviewed literature automatically.

But those are “if” statements layered on “if” statements. And underlying tension remains: a structured map of literature is most valuable to… other AI systems. It’s training data for the next generation of scientific LLMs. The project creates the very thing it needs to sustain itself, which is either brilliant or circular.

The Verdict: A Technical Triumph With a Use Case Problem

Project Aella represents genuine technical progress. Fine-tuning open models to match closed-source performance at 2% cost is no small feat. The QA evaluation methodology is rigorous. The visualization tool is immediately useful. The commitment to open releases, if followed through, could accelerate research in under-resourced institutions.

But the skepticism is warranted. Summaries without guaranteed factual accuracy are dangerous in scientific contexts. The value proposition for human researchers remains fuzzy, you still need to read the original papers for anything important. The name choice is a self-inflicted wound. And the crypto-adjacent compute model raises eyebrows in an academic community that’s seen too many “decentralize everything” projects fail.

The project’s success depends on what it enables next. If these summaries become the foundation for AI systems that can synthesize novel hypotheses, detect methodological flaws across thousands of papers, or generate systematic reviews automatically, then it’s a infrastructure layer for a new kind of science. If it’s just a better search engine, the “so what?” wins.

For now, go play with the visualizer. Click through the clusters, explore fields you’d never touch otherwise, and see the shape of human knowledge. That’s the immediate value. Whether anyone actually reads 100 million summaries is a question for 2026.