Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs just dropped Marble, and the AI community is already fighting about whether it’s revolutionary or a $230 million misfire. The generative 3D world model built on Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and Gaussian splatting promises to create explorable, stateful 3D environments in minutes, no video rendering required. But dig into the technical details and you’ll find a more interesting story: Marble exposes a philosophical fracture in how we define “world models”, and that fracture might matter more than the technology itself.

The $230M Elephant in the Room

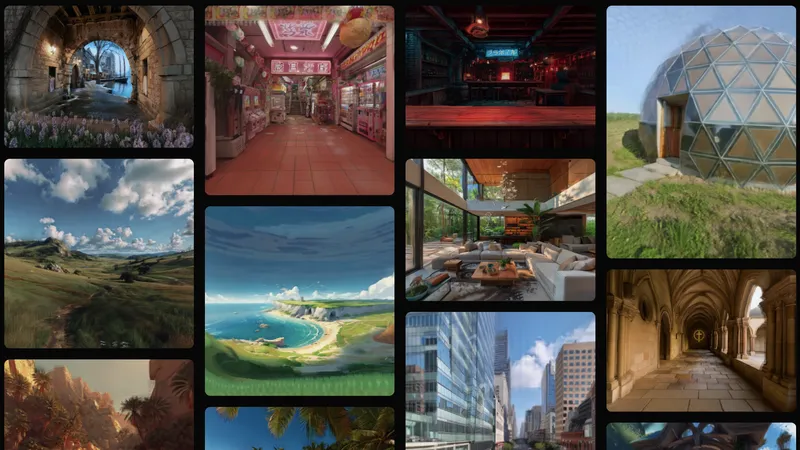

Let’s address the funding first. World Labs has raised $230 million in Series D funding from Andreessen Horowitz, NEA, and Radical Ventures, hitting a $1 billion valuation before most people could even try the product. The system generates 3D scenes from text, images, video, or coarse 3D layouts, exports to USDZ and GLB formats for Unity/Unreal/Blender, and runs natively on Vision Pro and Quest 3. For $20/month, you get enough credits to build worlds that others can explore and build upon.

The immediate criticism from technical observers is brutal: “This is not a world model.” They point out that Marble is essentially a sophisticated 3D scene generator that uses image generation and splatting techniques. The environments are small, often incoherent from multiple angles, and lack the geometric intelligence that defines true spatial reasoning. As one developer noted, “You might as well do text-to-image and then image-to-splat.”

That assessment isn’t wrong. But it might be missing the entire point.

What Marble Actually Does (And Why It Matters)

Marble’s architecture diverges sharply from the JEPA (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) framework that Yann LeCun champions for world models. Instead of learning predictive representations that model physics and causality, Marble builds dense clouds of Gaussian splats, millions of semitransparent colored blobs in 3D space, each with position, scale, rotation, color, and opacity. This isn’t a neural simulation of reality, it’s a compressed, editable representation of appearance.

The breakthrough isn’t in the splats themselves. It’s in the spatial intelligence that manipulates them. Marble lets you:

– Expand regions non-destructively

– Modify materials with text prompts

– Merge multiple worlds together

– Maintain persistent, stateful environments

This is where the “world model” debate gets messy. Traditionalists argue that without explicit physics modeling and causal reasoning, you can’t call it a world model. Practitioners counter that if a robot can navigate a warehouse using this representation, update it when the conveyor belt moves five feet, and share that updated model across a thousand units, you’ve built something more useful than a theoretical physics engine.

The Spatial Intelligence vs. Physics Simulation Divide

The controversy mirrors a larger split in AI research. On one side, researchers like LeCun pursue world models as internal simulations that understand physics and causality, essential for true artificial general intelligence. On the other, practitioners like Fei-Fei Li are building spatial intelligence systems that solve immediate problems in robotics, VR, and autonomous systems.

LeCun recently left Meta to launch AMI Labs, focusing on systems that “understand the physical world, have persistent memory, can reason, and can plan complex action sequences.” This approach demands fundamental breakthroughs in how models represent reality. Marble, by contrast, works now. It generates explorable scenes in minutes, not months of training.

This tension between theoretical purity and practical utility defines AI’s current moment. OpenAI’s GPT-4 doesn’t learn from experience once deployed, yet it’s transforming industries. Marble doesn’t model physics, yet it could revolutionize how we create virtual environments for training, design, and collaboration.

The Apple Comparison: Speed vs. Quality

Apple’s SHARP (open-source, on-device Gaussian splatting) highlights Marble’s tradeoffs. SHARP runs in under a second on consumer hardware, turning photos into volumetric scenes you can walk around. Marble takes minutes on server-side GPUs but produces more detailed, editable environments.

The difference is architectural philosophy. Apple optimized for immediacy, point your Vision Pro at a room, get a 3D scene instantly. World Labs optimized for mutability, create a world, edit it, merge it, share it. SHARP is a camera, Marble is a Photoshop for reality.

This raises questions about infrastructure costs. Marble’s computational expense makes it a premium service at $20/month, while SHARP is free and runs locally. For enterprises building thousands of virtual training environments, those costs add up fast, especially when consumer GPU acceleration is making local inference increasingly viable.

The “World Model” Pedigree Problem

Fei-Fei Li’s reputation intensifies the scrutiny. As the “godmother of modern AI” who pioneered ImageNet, her work carries weight. When she calls Marble a “world model”, people expect something that advances the fundamental science of spatial reasoning. What they got is a really good generative tool.

Critics argue this mislabels the achievement, inflating its importance. Supporters counter that we’re defining “world model” too narrowly. If the system can:

– Generate consistent 3D layouts from sparse inputs

– Support deterministic editing via text prompts

– Enable collaborative building across users

– Export to standard 3D pipelines

Then it’s modeling worlds in a way that matters for applications, even if it doesn’t simulate Newtonian physics.

This semantic battle reflects deeper anxieties about AI hype cycles. With generative AI models facing real-world deployment challenges and large AI ventures struggling with massive losses, the community is hypersensitive to overpromising. A $230M valuation for a tool that some see as incremental raises red flags.

The Real Innovation: Collaborative Spatial Editing

What gets lost in the debate is Marble’s most compelling feature: worlds as living documents. The ability to share an environment, have others modify it, and merge changes back creates a GitHub-like workflow for 3D spaces. This hasn’t existed before at this fidelity.

Imagine architecture firms collaborating on building designs, not by passing around files, but by editing the same spatial model. Or game designers building levels where each artist’s contributions merge automatically. Or robotics teams sharing warehouse layouts that update in real-time as the physical space changes.

This collaborative dimension transforms Marble from a generator into a platform. And platforms have a way of creating their own definitions. Photoshop didn’t just implement image processing theory, it defined what image editing meant for a generation.

The Bottom Line: Practicality Over Purity

Marble’s controversy ultimately reveals AI’s maturation. The field is splitting between research pursuing theoretical breakthroughs and engineering delivering practical tools. Both matter, but they answer to different masters.

World Labs chose the practical path. Their “world model” won’t help us understand consciousness or build AGI, but it might be the tool that makes VR collaboration actually work, or slashes the cost of creating training data for autonomous vehicles, or lets indie game developers build explorable worlds without a 3D art team.

The skepticism is healthy. We should question whether $230M is justified for a scene generator. We should demand more than “it’s not video” as a technical differentiator. But we should also recognize that sometimes the most impactful innovation isn’t the one that advances theory, it’s the one that changes practice.

Fei-Fei Li built her career on data that made deep learning practical. Marble might do the same for spatial AI, even if it doesn’t fit the textbook definition of a world model. In five years, we might not remember the debate. We’ll just be using the tools.

And if you’re still hung up on definitions? AI pioneer departing major tech firm to advance open world models shows there’s plenty of room for both approaches. The future belongs to whichever one ships.