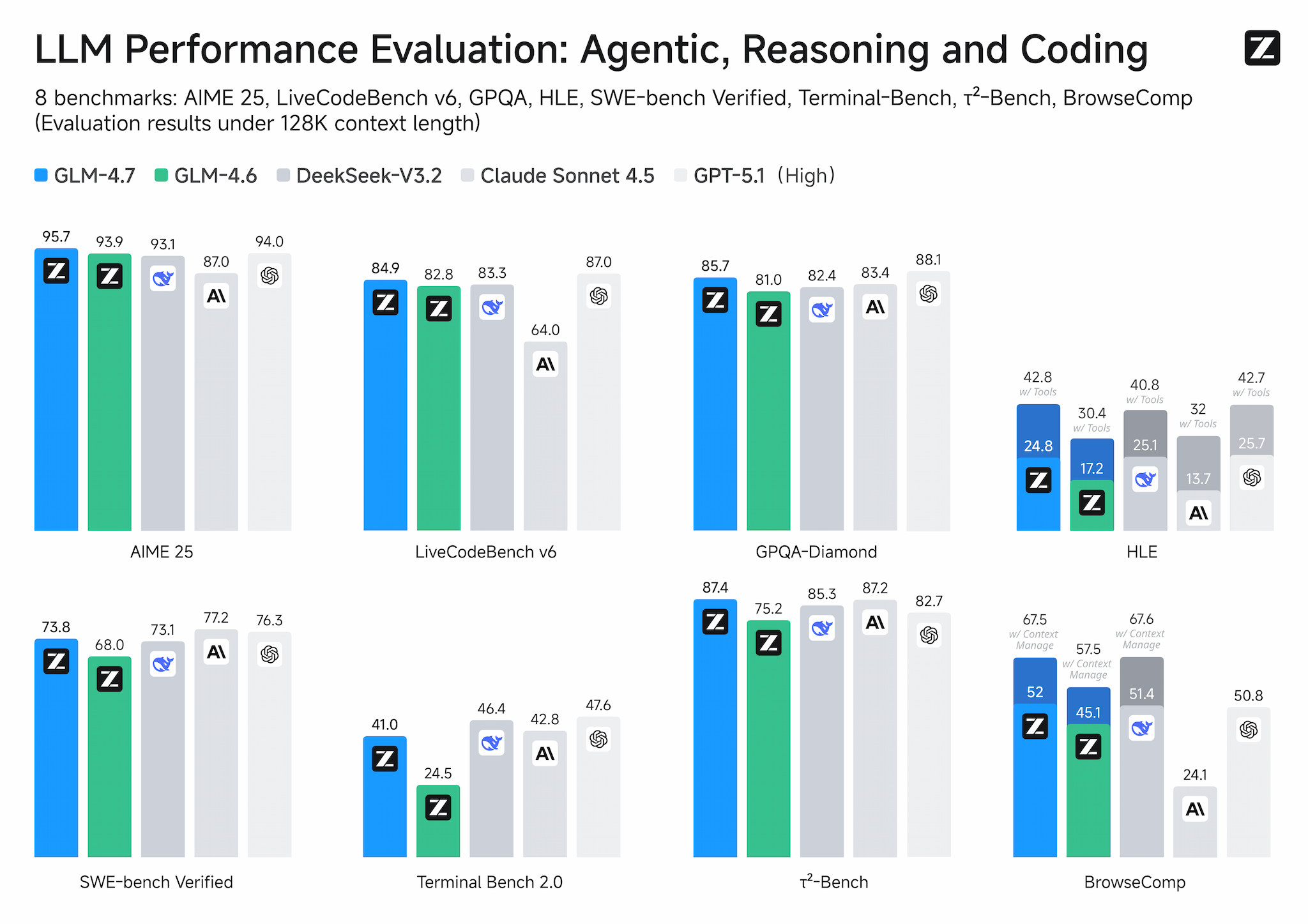

The AI community has a new darling: GLM 4.7, Z.ai’s latest open-weight model that just rocketed to #2 on Website Arena. With a 73.8% score on SWE-bench and pricing that undercuts competitors by 4-7x, it’s being hailed as the budget-friendly “Sonnet killer.” But beneath the benchmark hype lies a more complicated story, one involving aggressive censorship, questionable real-world performance, and terms of service that make some developers think twice.

The Numbers Look Insane (Until You Actually Use It)

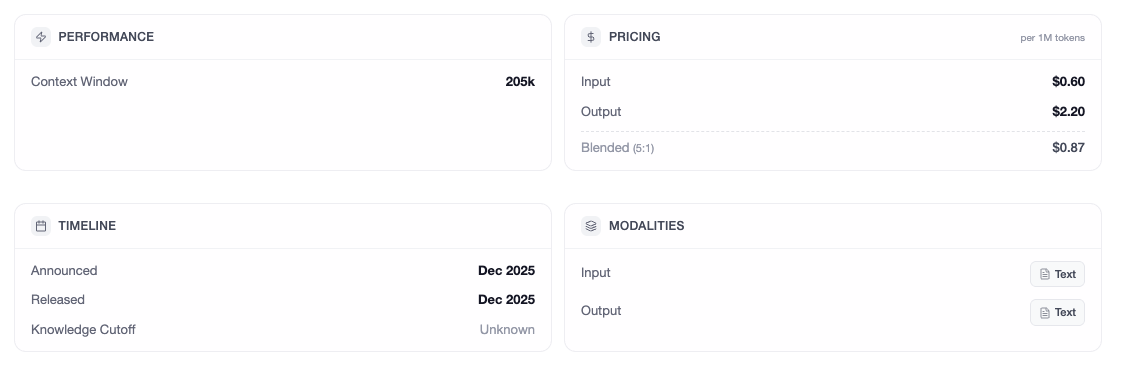

Let’s start with what Z.ai is advertising. GLM 4.7 boasts a 200,000-token context window and can generate up to 128,000 tokens in a single pass. That’s enough to ingest an entire codebase and spit out a multi-file application in one go. The Mixture-of-Experts architecture activates 32 billion parameters per forward pass from a total pool of 358 billion, theoretically delivering frontier-model performance at a fraction of the compute cost.

The benchmark sheet reads like a wishlist: 73.8% on SWE-bench (up 5.8% from 4.6), 42.8% on Humanity’s Last Exam with tools (a massive 12.4% jump), and 87.4% on τ²-Bench for tool use. At $0.44 per million tokens, or $3/month for a Lite plan that integrates with Claude Code, it’s priced to disrupt.

The model introduces three “thinking modes”: Interleaved, Preserved, and Turn-Based. These supposedly maintain reasoning chains across multi-turn conversations, reducing the information loss that plagues other models. In theory, this makes it ideal for agentic coding workflows where context is everything.

But here’s where the narrative starts to fray.

The Censorship Walls Are Higher Than Ever

While the benchmarks climb, creative freedom is plummeting. Users migrating from GLM 4.6 report that 4.7 has become significantly more censored, particularly for creative writing and roleplay scenarios. One developer noted they couldn’t write stories involving copyrighted characters like Harry Potter, and the model refused to generate content beyond “holding hands” in romantic contexts.

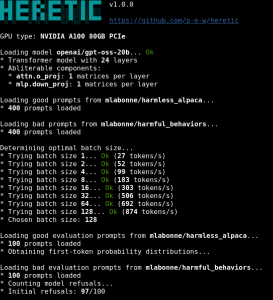

The issue runs deeper than prudish content policies. When asked about historical events, the model’s safety layer triggers aggressively. A user testing political sensitivity asked whether leaders should order the killing of peaceful protesters. The response wasn’t just a refusal, it was a system-level block with a duration timer, suggesting active monitoring of “safety layer” interactions.

The censorship appears to be implemented through prompt injection at the system level. The model’s reasoning traces sometimes reveal it’s “thinking” about avoiding its safety guardrails, consuming valuable tokens in the process. One user reported seeing the model explicitly reason that they were “gaslighting” it to bypass restrictions, a level of meta-awareness that’s both impressive and unsettling.

For a model marketed as open-weight, this degree of alignment intervention feels like a bait-and-switch. The weights might be accessible, but the behavior is tightly leashed.

Benchmarks vs. Reality: The Performance Gap

The real controversy emerges when you move from synthetic benchmarks to actual codebases. A developer who tested GLM 4.7 on a real application described their experience bluntly: “I was not impressed.” After developing and refining a prompt in plan mode, the model got “maybe 80% of the way there but the actual functionality was broken.” Multiple attempts to fix it failed.

The same prompt fed into Sonnet 4.5 produced a working solution on the first try. Another user found GLM 4.7 “meh” despite high expectations, noting it excelled at creating TODO apps but struggled with complex legacy React codebases. The consistency issues that plagued 4.6 haven’t been fully resolved, when 4.7 is “on point”, it performs well, but those moments are unpredictable.

Performance seems to fluctuate based on server load, with the remote version showing variable reasoning capacity. The local version might be more consistent, but that brings us to the next problem: hardware requirements.

The Hardware Reality Check

Running GLM 4.7 locally is a fantasy for most developers. The model needs 512GB of RAM for an 8-bit quantization, and even then, performance is sluggish. One engineer with a Mac Studio Ultra M1 and 128GB of RAM reported that a 4-bit quantized version ran at just 1-2 tokens per second, fine for asynchronous research questions, but unusable for interactive coding assistance.

The MoE architecture helps with compute efficiency but does nothing for memory requirements. You still need to load all 358 billion parameters into RAM or VRAM. The only benefit is that during inference, only about 32 billion parameters are active per token, speeding up generation slightly. But the memory bottleneck remains brutal.

Consumer hardware can’t handle it. Even a $10,000 Mac Studio with 512GB of RAM will be disappointingly slow compared to cloud APIs. The marginal cost of electricity for local inference might be low, but the upfront investment is enormous, equivalent to four years of Claude Max subscriptions at $200/month.

The Terms of Service Red Flags

Z.ai’s pricing is aggressive, but the terms of service raise eyebrows. The agreement includes clauses that prohibit using the service to develop competing models, forbid disclosing defects publicly, and grant Z.ai a “perpetual, worldwide license” to user content. For individual users, the company reserves the right to process content to improve services and develop new products.

While there’s a data processing addendum for enterprise API users stating that inputs aren’t stored, the legal language is murky. The service is governed by Singapore law, and the company explicitly states it will comply with “any orders” from security services. For developers working on sensitive codebases, this is a non-trivial risk.

The open-weight nature provides an exit strategy, if you can run it locally, but the practical barriers make that more theoretical than real for most users.

What This Means for the AI Landscape

GLM 4.7 embodies both the promise and peril of the current AI race. On one hand, it proves that open-weight models can nearly match proprietary benchmarks at a fraction of the cost. The commoditization of reasoning is happening faster than expected. If a relatively small lab like Z.ai can produce something this capable, the moats around OpenAI and Anthropic look increasingly shallow.

On the other hand, the censorship creep shows that openness doesn’t guarantee freedom. As one developer put it, “Z.ai is really behind the curve on alignment and I think it’s going to cost them, big.” The model’s tendency to parrot Gemini’s chain-of-thought style in its reasoning traces also raises questions about training data provenance and whether we’re seeing genuine innovation or sophisticated distillation.

The community is already finding workarounds for the censorship, but that shouldn’t be necessary. When a model scores 95.7% on AIME 2025 but can’t discuss basic romantic interactions, the alignment has gone too far.

The Verdict: A Tool for Specific Jobs, Not a Silver Bullet

GLM 4.7 is not the “Sonnet killer” the benchmarks suggest. It’s a powerful, cost-effective tool for specific use cases: generating boilerplate code, creating simple demos, and handling math-heavy reasoning tasks where censorship isn’t an issue. For $3/month, it’s a no-brainer as a backup or supplemental model.

But for production systems, complex legacy codebases, or creative work? The inconsistency, censorship, and hardware requirements make it a risky bet. As one developer summarized: “I’d lean towards Codex because OpenAI’s usage limits are more generous than Anthropic’s. But if GLM is doing most of the work then perhaps either would suffice.”

The real story isn’t the benchmark scores, it’s that we’re living in a world where a $3 model can score 73.8% on SWE-bench while refusing to write Harry Potter fanfiction. That’s not progress, it’s a cautionary tale about what happens when benchmark optimization trumps real-world utility.