Bypassing SQL for 60% Performance Gains: Brilliant Engineering or Dangerous Heresy?

The first time you see the benchmark numbers, you assume someone made a mistake. A 60% performance improvement by removing functionality? That’s not how optimization works, until you realize we’ve been paying a massive abstraction tax for features we never use.

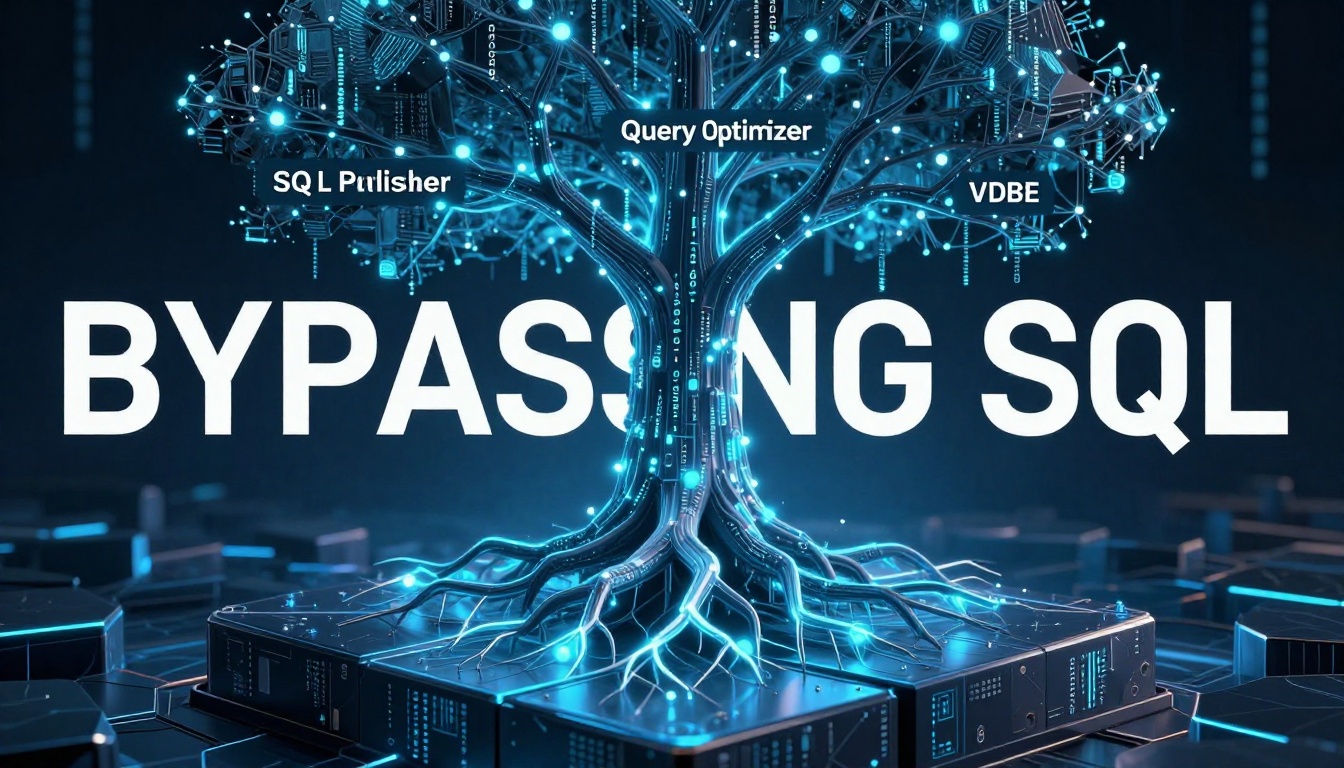

Meet SNKV, a key-value store that commits what some database purists would call architectural blasphemy: it bypasses SQLite’s entire SQL processing stack and talks directly to the B-Tree layer. No parser. No virtual machine. No query optimizer. Just raw, direct B-Tree operations wrapped in a 2,400-line C library. And yes, it keeps ACID compliance intact.

The Performance Numbers That Start Fights

Let’s get the controversial part out front. Running identical workloads (50,000 records, 70% reads, 20% writes, 10% deletes), SNKV delivers:

- Mixed workload: 210,916 ops/sec vs SQLite’s 129,999 ops/sec (+62%)

- Random reads: 219,050 ops/sec vs 173,863 ops/sec (+26%)

- Sequential scans: 3,025,534 ops/sec vs 2,138,485 ops/sec (~1.4×)

- Random deletes: 105,890 ops/sec vs 62,728 ops/sec (+69%)

SQLite wins on sequential writes and existence checks, but those are edge cases. For the workloads that dominate real applications, mixed operations with heavy read bias, SNKV dominates.

The secret? SNKV doesn’t just optimize around SQL, it eliminates the SQL interface layer entirely. As the project’s architecture diagram brutally illustrates, it surgically removes the tokenizer, parser, code generator, VDBE executor, and query optimizer. What remains is the battle-tested B-Tree engine, pager module, and OS interface that make SQLite reliable in the first place.

How Deep the Rabbit Hole Goes

To understand why this matters, you need to grasp what the DEV Community’s SQLite deep-dive calls “the tree module”, the layer that transforms SQLite from a page-oriented storage system into a tuple-oriented database. The tree module doesn’t care about your schema, column types, or SQL semantics. It stores variable-length byte sequences and keeps them ordered. That’s it.

This is precisely what a key-value store needs. When you call kvstore_put("user:123", "Alice Johnson"), SNKV directly invokes the B-Tree insertion logic without first constructing a SQL string, parsing it into an AST, generating bytecode, and executing it through a virtual machine. Each of those steps adds overhead, measurable, significant overhead that compounds under load.

The architecture is ruthlessly simple:

Application → KVStore Layer (~2400 LOC) → SQLite B-Tree Engine → Pager Module → DiskCompare this to SQLite’s normal path:

Application → SQL Interface → SQL Compiler → Virtual Machine → Backend Layer → B-Tree Engine → Pager Module → DiskFour extra layers. That’s not a minor implementation detail, it’s an architectural tax you’re paying on every single operation.

The Transaction Management Reality Check

Here’s where the controversy gets spicy. The DEV Community’s analysis of SQLite’s transaction management reveals that the pager layer, which SNKV keeps unchanged, is where the real magic happens. The pager handles locking, journaling, and crash recovery. It provides the “I” in ACID.

When SNKV calls kvstore_begin(), it’s leveraging the same sqlite3PagerWrite() mechanism that SQLite uses internally. The pager acquires reserved locks, writes before-images to the rollback journal, and ensures isolation. The tree module modifies pages in memory, but the pager decides when and how those changes become durable.

This demolishes the first objection purists raise: “But you’re sacrificing ACID!” No, you’re not. You’re sacrificing abstraction, not durability. SNKV inherits SQLite’s proven crash safety, atomic commits, and WAL mode for concurrent readers and writers. The transaction management analysis shows that once sqlite3PagerWrite returns, the tree module can modify pages freely, protected by the pager’s state machine.

The performance gains don’t come from cutting corners. They come from eliminating redundant work.

When Architectural Purity Becomes a Performance Anchor

This is where the debate gets personal for many developers. We’ve been taught that abstraction is good, layers are protective, and you should never bypass the public API. These principles serve us well, until they don’t.

Consider the MySQL insertion trap where performance pitfalls emerge when scaling database writes. The first 5 million records take five minutes. The next 5 million take an hour. By 250 million records, your pipeline is a cautionary tale. The problem isn’t MySQL’s storage engine, it’s the accumulation of overhead from features you don’t need for your specific workload.

SNKV’s philosophy is blunt: If you don’t need SQL, don’t pay for it. This challenges the “one size fits all” database mindset that has dominated for decades. It’s the same principle behind eliminating abstraction layers for performance in AI data systems, sometimes the generalized solution is 60% slower than the specialized one.

The Syncthing community’s debate over a 7× speedup using lock-less metadata handling reveals similar tensions. One developer’s optimization is another’s “dangerous tradeoff.” The core disagreement? Whether database myths are influencing architectural decisions under load, causing teams to stick with familiar-but-slow patterns instead of exploring direct storage access.

The Implementation: Surprisingly Boring

What’s remarkable about SNKV is how unremarkable the code looks. Opening a database:

KVStore *pKV;

kvstore_open("mydb.db", &pKV, 0, KVSTORE_JOURNAL_WAL);

Storing a value:

kvstore_put(pKV, "key", 3, "value", 5);

Retrieving it:

void *pValue, int nValue;

kvstore_get(pKV, "key", 3, &pValue, &nValue);

printf("%.*s\n", nValue, (char*)pValue);

sqliteFree(pValue);

The API is intentionally boring because the innovation isn’t in the interface, it’s in what’s not happening underneath. No prepared statements. No query plan caching. No schema validation. Just direct B-Tree operations.

The benchmark code is equally straightforward. The SQLite comparison uses standard INSERT and SELECT statements, while SNKV uses the API above. The difference isn’t algorithmic complexity, it’s the elimination of abstraction.

When to Use It (And When Not To)

SNKV’s documentation is refreshingly honest about its limitations. It’s ideal for:

- Embedded systems with low memory

- Configuration stores

- Metadata databases

- C/C++ applications needing fast KV access

- Systems that do not need SQL

If you need joins, ad-hoc queries, or analytics, use SQLite. If you need fast, reliable key-value storage, use SNKV.

This is the crucial distinction that makes the approach defensible. SNKV isn’t trying to replace SQLite, it’s carving out a specialized niche where SQL is pure overhead. The trade-offs between SQL abstraction and direct storage access mirror broader debates in data engineering: when does the convenience of a general-purpose system outweigh the performance cost?

The answer depends on your access patterns. The architectural implications of data access patterns and storage boundaries matter more than ever. If your domain logic is essentially get(key) and put(key, value), you’re leaking performance through an abstraction you never fully utilize.

The Heresy and the Truth

The spicy take isn’t that SQL is bad, it’s that unnecessary abstraction is expensive. SNKV proves that SQLite’s value isn’t in its SQL parser, it’s in the B-Tree engine and pager that D. Richard Hipp spent decades refining. Those layers are general-purpose enough to support a SQL frontend, but they don’t require it.

This challenges how we evaluate embedded databases. Instead of asking “What’s the most feature-rich database I can embed?” we should ask “What’s the minimal layer I need to solve this problem?” Sometimes that’s SQLite with SQL. Sometimes it’s SNKV. Sometimes it’s a custom B-Tree implementation.

The controversy stems from breaking a social contract: Thou shalt not bypass the public API. But in systems programming, that contract is negotiable. The Linux kernel doesn’t hide its internal APIs from drivers. PostgreSQL exposes extension hooks that bypass the planner. SQLite’s B-Tree layer is public enough to be documented in source code and academic papers.

What SNKV does is expose what was already there, just hidden behind layers designed for a different use case.

The Real-World Impact

The performance difference isn’t academic. In the session store example, SNKV handles user authentication with predictable latency. In the configuration manager, it separates dev and production settings with column families. In the cache implementation, it evicts expired entries with direct cursor traversal, 1.4× faster than scanning through SQL.

These aren’t synthetic benchmarks, they’re patterns that appear in production systems. The difference between 130,000 ops/sec and 210,000 ops/sec is the difference between needing a cache layer and not needing one. It’s the difference between serving a request from memory and hitting disk. It’s the difference between a responsive UI and a sluggish one.

SNKV’s 60% performance gain isn’t magic. It’s the result of questioning assumptions that most developers never think to challenge. The SQL layer in SQLite is a brilliant piece of engineering, if you need SQL. If you don’t, it’s a 60% tax on every operation.

The project forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: how database myths influence architectural decisions under load. We’ve become so conditioned to believe that abstraction is free (or cheap) that we stop measuring its cost. SNKV measures it, and the number is 60%.

Is bypassing SQL heresy? Only if you believe the interface is more important than the problem it solves. For key-value workloads, the emperor has no clothes, and SNKV just proved it.

The question isn’t whether this approach is “allowed.” The question is: how much performance are you willing to leave on the table to avoid offending architectural sensibilities?

Ready to challenge your own database assumptions? The SNKV source code is available at github.com/hash-anu/snkv, complete with benchmarks, examples, and that gloriously simple 2,400-line implementation that makes SQL purists nervous.