The Graphics API is Dead: Why Direct GPU Programming Just Became Inevitable

The graphics programming community has been living a lie. For a decade, we’ve accepted that “modern” APIs like Vulkan and DirectX 12 represent the pinnacle of low-level GPU control. We’ve swallowed the complexity, descriptor sets, pipeline state objects, barrier hell, because we believed the performance gains justified the pain. But what if I told you that every major GPU vendor has already built the hardware that makes these APIs obsolete? And that you can implement a fully functional graphics system in roughly 150 lines of code?

This isn’t speculation. It’s the conclusion drawn from a career spent watching GPU architecture evolve from the 3dfx Voodoo 2 to today’s silicon behemoths. The signs have been there: Nvidia’s gaming revenue now accounts for just 10% of their business while AI workloads dominate at 90%. AMD’s RDNA architecture features fully coherent L2 caches. Apple Silicon gives you raw 64-bit GPU pointers. The hardware has moved on. The software just hasn’t caught up.

The 30-Year API Debt Crisis

To understand why we’re here, you need to appreciate the historical baggage. The original DirectX and OpenGL specifications were designed around hardware like the 3dfx Voodoo 2, a three-chip design with separate memory pools for framebuffers and textures. APIs had to abstract away the fact that your graphics card was essentially a glorified blitter with no unified memory model.

That 30-year-old design DNA still infects today’s APIs. When Nvidia coined the term “GPU” with the GeForce 256, they added a transform engine but kept the split memory model. DirectX 7 introduced render target textures, but the API still had to pretend that reading from the rasterizer output was a special operation requiring explicit support. Each evolution, shader models, compute shaders, ray tracing, bolted onto this creaking foundation rather than replacing it.

The result? Vulkan 1.4 ships with a 20,000-line header file. DirectX 12’s barrier system requires tracking resource states that the GPU driver immediately discards. And game developers now ship with 100GB+ Pipeline State Object (PSO) caches because every combination of render state needs a pre-compiled microcode blob.

Modern GPUs Have Already Left APIs Behind

Here’s the kicker: today’s hardware hasn’t just evolved, it’s fundamentally different. All modern GPU architectures feature:

- Unified memory access via PCIe ReBAR or UMA, allowing CPUs to write directly to GPU memory

- Fully coherent cache hierarchies where the last-level cache sees all memory operations

- Bindless texture samplers that treat descriptors as raw memory

- Generic load/store paths that bypass the texture sampler entirely

AMD’s RDNA architecture (2019) finally integrated the display engine and decompressor into the coherent L2 cache. Nvidia’s Turing (2018) gave us mesh shaders and scalar execution units. Apple Silicon unified the memory model completely. Yet we’re still using APIs designed for GCN-era hardware that required manual cache flushes and explicit layout transitions.

The performance implications are stark. Modern GPUs can execute raw memory loads with 2-3x lower latency than texel buffer fetches. Wide 128-bit loads reduce instruction count by 4x compared to element-wise access. And pointer-based data structures enable algorithms that would be impossible with descriptor-bound resources.

The PSO Permutation Apocalypse

Let’s talk about that 100GB PSO cache problem. When DirectX 12 and Vulkan launched, they promised cheaper draw calls through pre-baked pipeline state. In reality, they shifted complexity from runtime to build time, and exploded it. Every combination of:

- Vertex layout

- Blend mode

- Depth test

- Stencil operation

- Shader specialization constants

- Render target format

…requires a separate PSO. Game engines now compile thousands of permutations, storing them in massive caches that take ages to load and still cause stutter when a new combination appears. Valve and Nvidia maintain terabyte-scale cloud databases of pre-compiled PSOs for every driver/hardware combination.

This isn’t a theoretical problem. At Ubisoft, porting DirectX 11 renderers to DirectX 12 often resulted in performance regression despite the “lower overhead” API. The binding model created a new driver layer beneath the driver, tracking resources just like the old APIs did.

A 150-Line API That Actually Works

What if we stopped pretending that shaders need special binding tables and descriptor sets? What if we treated GPU memory like… memory?

Here’s the core of a modern graphics API designed for 2025 hardware:

// Allocate GPU memory like you would CPU memory

uint32_t* numbers = gpuMalloc<uint32_t>(1024);

// Write directly from CPU (UMA/ReBAR makes this fast)

for (int i = 0, i < 1024, i++) numbers[i] = random();

// Pass a single pointer to the shader

gpuDispatch(commandBuffer, dataGpu, uvec3(128, 1, 1));No buffer objects. No descriptor sets. No bind groups. The shader receives a single 64-bit pointer and does pointer arithmetic like it’s 1972:

[groupsize = (64, 1, 1)]

void main(uint32x3 threadId : SV_ThreadID, const Data* data)

{

uint32 value = data->input[threadId.x],

data->output[threadId.x] = value;

}The entire API surface, including memory management, texture creation, pipeline setup, barriers, and command recording, fits in 150 lines. Compare that to Vulkan’s 20,000-line header or WebGPU’s 2,700-line Emscripten binding.

Memory Management Without the Ceremony

Modern GPU memory management is simple: allocate a chunk, get a CPU-mapped pointer, write to it. The gpuMalloc design borrows from CUDA but adds the critical piece that makes it suitable for graphics, support for CPU-mapped GPU memory:

void* gpuMalloc(size_t bytes, MEMORY memory = MEMORY_DEFAULT);

void* gpuHostToDevicePointer(void* ptr);

The MEMORY type parameter handles the only remaining complexity: private GPU memory for compressed textures and buffers. For most data, uniforms, descriptors, draw arguments, you want MEMORY_DEFAULT, which gives you a persistently mapped pointer that both CPU and GPU can access at full speed. For textures, you allocate GPU-private memory and use a copy command that handles swizzling and compression.

This model eliminates the Vulkan design flaw where you create a VkBuffer first, then query which memory types it supports, forcing a lazy allocation pattern that’s prone to runtime hitches. Instead, you allocate memory up front and sub-allocate from it like a sane person.

Shaders as Plain C Code

The shader language implications are profound. HLSL and GLSL were designed as 1:1 elementwise transform languages, vertex in, vertex out, pixel in, pixel out. They never evolved beyond that framework, which is why we have 16 different shader entry points and zero library ecosystem.

CUDA, by contrast, has a thriving library ecosystem because it’s just C++ with GPU intrinsics. The same approach works for graphics:

struct alignas(16) Data

{

float16x4 color;

const uint8_t* lut;

const uint32_t* input;

uint32_t* output;

};

[groupsize = (64, 1, 1)]

void main(uint32x3 threadId : SV_ThreadID, const Data* data)

{

uint32 value = data->input[threadId.x];

// Use LUT, apply color, etc.

data->output[threadId.x] = processed;

}The compiler performs automatic uniformity analysis, wide load coalescing, and register packing. You get the performance of hand-tuned shader code from simple, readable C. Pointer arithmetic replaces descriptor indexing. Const correctness replaces binding flags. And you can finally write reusable functions that accept arrays, something HLSL and GLSL still can’t do properly.

Barriers That Don’t Suck

The most hated feature in modern graphics APIs is barriers. Developers track resource states that drivers ignore. The GPU command processor doesn’t care about your texture layouts, it cares about cache coherency hazards.

Modern barriers should be simple:

gpuBarrier(commandBuffer, STAGE_COMPUTE, STAGE_COMPUTE);

This flushes the tiny L0 and scalar caches that aren’t automatically coherent. That’s it. No resource list. No layout transitions. The AMD GCN-era requirement to decompress DCC textures before sampling? Gone on RDNA, the decompressor sits between L2 and L0. The need to flush ROP caches? Handled automatically when you use raster stages.

Special cases remain: writing indirect arguments requires stalling the command processor prefetcher. Modifying descriptor heaps needs invalidating the sampler cache. But these are rare operations that deserve explicit flags, not the default path:

// Only when you actually write draw arguments

gpuBarrier(commandBuffer, STAGE_COMPUTE, STAGE_COMPUTE, HAZARD_DRAW_ARGUMENTS);

Metal 2 already does this. Vulkan’s new VK_KHR_unified_image_layouts extension (2025) removes layout transitions. The hardware has been ready for years.

The Tooling Problem (And Why It’s Not)

“But how do you debug raw pointers?” The same way you debug CPU code. Modern GPU debuggers follow pointer chains through virtual address spaces. CUDA and Metal have proven this works, the debugger shows struct layouts, follows pointers, and visualizes textures referenced by handle.

The only requirement: GPU capture tools must be able to replay allocations at identical virtual addresses. DX12 and Vulkan’s Buffer Device Address extensions already provide this via RecreateAt and VkMemoryOpaqueCaptureAddressAllocateInfo. The tooling infrastructure exists.

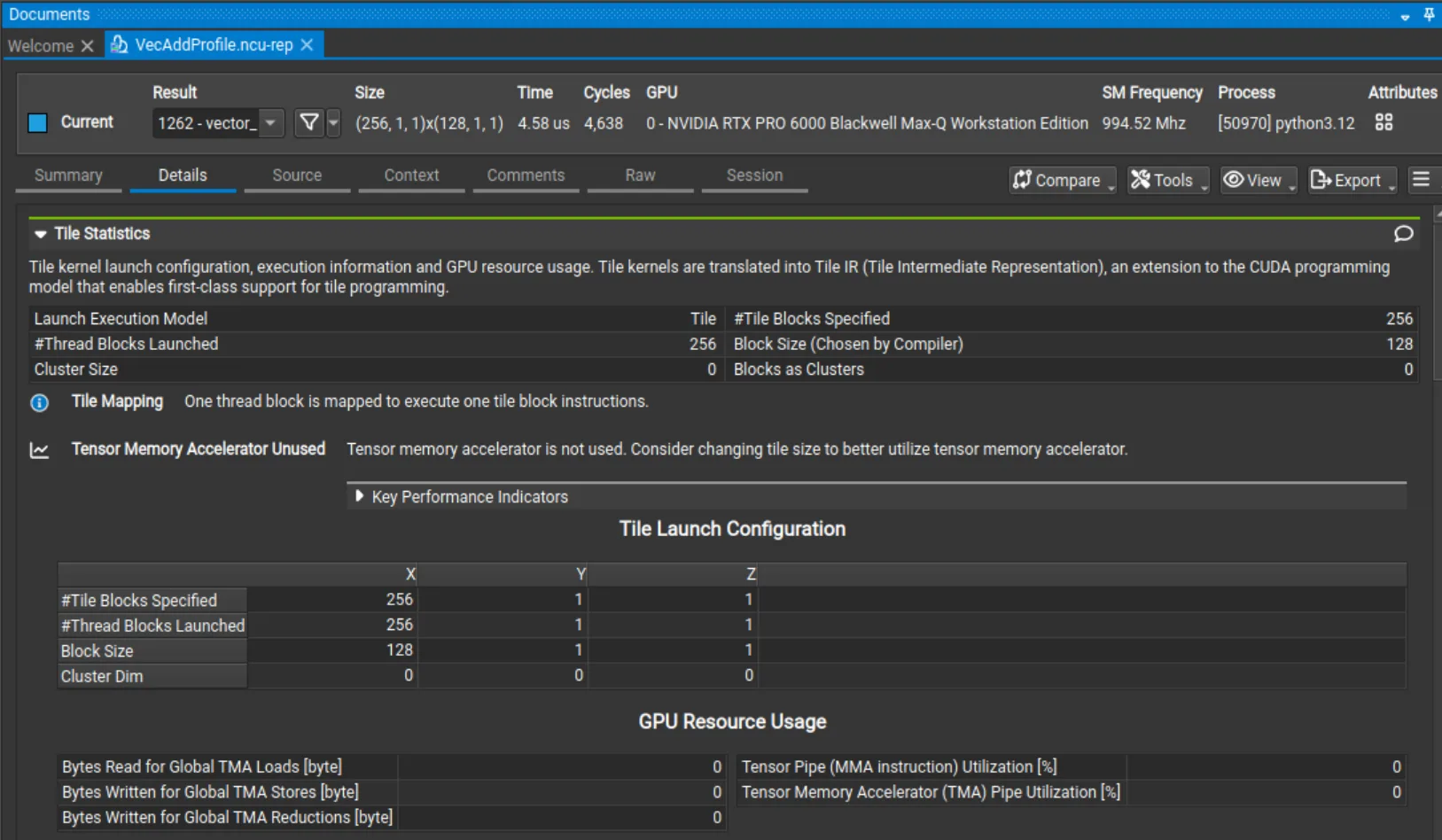

Performance tools benefit too. Nsight Compute’s Tile Statistics show you exactly how your warps utilize tensor cores and memory pipes. Profiling a pointer-based shader is no different than profiling a descriptor-based one, the addresses resolve to the same hardware counters.

Translation Layers: The Compatibility Bridge

Dropping existing APIs seems radical, but translation layers prove it’s practical. MoltenVK maps Vulkan to Metal by generating argument buffers, structs containing 64-bit pointers and texture handles. Proton maps DX12 to Vulkan using the descriptor buffer extension. These layers are already doing the heavy lifting of converting descriptor-based APIs to pointer-based ones.

A “no graphics API” API would simply expose the underlying model directly. Translation from Vulkan would:

- Allocate a contiguous descriptor heap range for each descriptor set

- Store a single 32-bit base index instead of per-binding handles

- Generate root structs with 64-bit pointers for each buffer

- Emit vertex fetch code from the vertex layout declaration

The result? Native performance with compatibility. Old games run through translation while new engines target the simplified interface directly.

Minimum Viable Hardware

This isn’t future hardware, it’s already in your machine. The minimum spec includes:

- Nvidia Turing (RTX 2000 series, 2018): Mesh shaders, scalar units, hacked ReBAR support

- AMD RDNA2 (RX 6000 series, 2020): Coherent L2, DCC everywhere, bindless descriptors

- Intel Xe (2022): SM 6.6 heap support, UMA on integrated parts

- Apple M1/A14 (2020): Full pointer semantics in Metal 4

- ARM Mali-G710 (2021): Command streams, descriptor buffers

- Qualcomm Adreno 650 (2019): Turnip open-source drivers expose the necessary extensions

If your GPU is newer than 5 years old, it supports this model. The hardware capability is universal, only the software has lagged.

The Performance Reality Check

Let’s quantify the win. The blog post’s examples show several key optimizations:

Vertex Fetch: Traditional APIs require binding vertex buffers and declaring layouts to the driver. With shader-based fetch:

Vertex vertex = data->vertices[vertexIndex];

The GPU issues a single wide load (128-bit) and unpacks in registers. This eliminates driver overhead and gives you explicit control over caching. For complex vertex formats, you can split position and attributes to benefit TBDR GPUs, something the fixed-function vertex fetch can’t do.

Texture Access: Bindless descriptors reduce register pressure. A 32-bit index uses one SGPR, a 256-bit descriptor uses eight. In ray tracing where texture indices are non-uniform, the difference is dramatic. Nvidia and Apple GPUs handle per-lane indices in hardware, AMD scalarizes in software. The index approach wins everywhere.

Barriers: Removing resource lists saves significant CPU time. Vulkan drivers spend cycles converting your VkImageMemoryBarrier array into a handful of cache flush flags. Skip the list, pass the flags directly, and you’ve freed up both CPU and driver overhead.

The cumulative effect? Frame time reductions of 0.5-2ms are realistic for CPU-bound engines. More importantly, pipeline creation time drops from hundreds of milliseconds to microseconds. No more shader compilation stutter. No more PSO cache warm-up.

The Controversial Truth

Here’s where I lose friends: Abstraction layers made sense when GPUs were exotic co-processors with split memory and fixed-function pipelines. Today, they’re just massively parallel CPUs with wide vector units.

We don’t wrap x86 instructions in descriptor sets. We don’t require barriers to use the L2 cache on a Ryzen CPU. The only reason we accept this for GPUs is inertia.

CUDA proved that direct memory access and pointer-based programming models work at scale. Nvidia’s $4T valuation owes much to the ecosystem built around this simple abstraction. Graphics stuck with the old model because of backwards compatibility, and because the Khronos Group and Microsoft couldn’t coordinate a clean break.

But the cracks are showing. AI workloads already bypass graphics APIs entirely. Compute shaders are just the beginning. When Unreal Engine’s Nanite rasterizes in compute and Lumen ray traces without fixed-function pipelines, you’re witnessing the API’s obsolescence in real-time.

Conclusion: Embrace the Inevitable

The “No Graphics API” concept isn’t about abandoning standards, it’s about aligning them with reality. The hardware has been ready since 2018. The tooling is mature. The performance benefits are measurable. The only missing piece is consensus.

Vulkan’s extension treadmill (VK_EXT_descriptor_buffer, VK_KHR_unified_image_layouts) proves the spec writers see the problem. Metal 4’s pointer support shows Apple is willing to break from tradition. CUDA’s dominance demonstrates developer appetite for simpler models.

The path forward is clear: a minimal, pointer-based API that exposes GPU memory as memory, shaders as C code, and synchronization as cache control. Legacy code runs through translation layers. New code targets the simplified interface. Performance improves. Complexity vanishes.

The graphics API isn’t just dead, it’s been zombie-walking for a decade, kept alive by driver complexity and backwards compatibility. Modern GPUs deserve better. Developers deserve better. It’s time to let the old ways die and build systems that speak directly to the silicon.

Your move, Khronos.