Soprano-80M: The 2000x TTS Speedup That Makes Real-Time Voice AI Finally Real, And Exposes Everything Broken About the Field

Soprano-80M doesn’t just push the boundaries of text-to-speech performance, it demolishes them so completely that it forces a uncomfortable question: what have we been optimizing for all these years? With sub-15 millisecond streaming latency and 2000x real-time generation on an A100, this 80-million-parameter model from a second-year undergrad makes industry-leading systems look like they’re running on dial-up. But the real controversy isn’t the speed, it’s what the model’s glaring weaknesses reveal about the TTS field’s misplaced priorities.

The Performance Numbers That Break the Benchmark Game

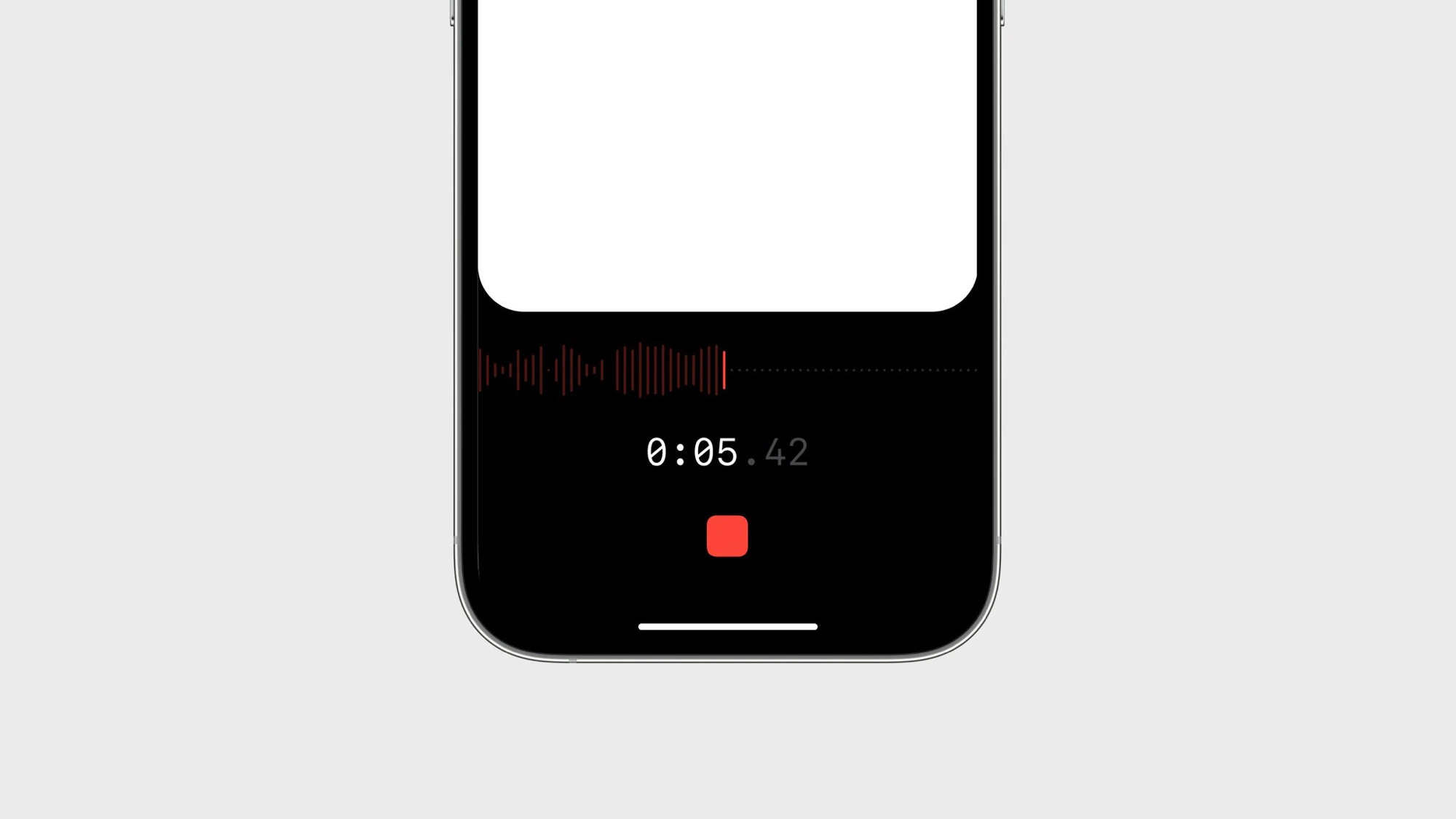

Let’s start with the specs that made the AI community do a collective double-take. Soprano-80M achieves <15ms first-chunk latency when streaming, roughly 10x faster than previous speed champions like Chatterbox Turbo or CosyVoice3. In batch mode, it generates 10 hours of 32 kHz audio in under 20 seconds on an A100, that’s a real-time factor (RTF) of approximately 2000x. Even on a consumer RTX 4070, it hits ~1000x RTF.

The memory footprint is equally absurd: under 1GB VRAM for the full pipeline. For context, that’s smaller than most Stable Diffusion checkpoints, yet it’s running a complete TTS system.

But here’s where it gets spicy: this performance comes from a model trained on just 1,000 hours of audio, roughly 100x less data than competitors like XTTS or commercial alternatives. The author, Eugene Kwek, openly admits this limitation on the project’s GitHub repository, which makes the speed achievements either a masterclass in efficient architecture or a flashing warning sign about robustness.

The Architectural Heresy That Enables the Speed

Soprano’s breakthrough isn’t magic, it’s a series of deliberate design choices that prioritize speed over everything else, including some conventional wisdom about audio quality.

1. The Vocos Decoder Gambit

Most modern TTS systems use diffusion-based decoders to convert linguistic features into waveforms. Soprano throws this out the window, replacing it with a Vocos-based vocoder that runs at ~6000x real-time. The trade-off? Diffusion models are computationally expensive because they’re iterative refinement processes. Vocos is a feed-forward convolutional architecture that sacrifices some of the fine-grained control diffusion provides for pure speed.

The decoder’s finite receptive field becomes a feature, not a bug. Because Vocos only “sees” a limited context window, Soprano can exploit this locality to skip crossfading entirely during streaming. Traditional streaming TTS generates overlapping chunks and blends them, introducing artifacts. Soprano’s streamed output is bit-for-bit identical to its offline generation, with audio starting after just five tokens.

2. The 0.2 kbps Neural Codec

Soprano compresses speech to ~15 tokens per second at 0.2 kbps using a novel neural audio codec. That’s 40% fewer tokens than the 25 tokens/sec used by many codecs, and an order of magnitude lower bitrate than traditional codecs like Opus. The codec achieves the highest bitrate compression ratio of any audio codec, according to the author, which directly translates to faster generation since the LLM has fewer tokens to produce per second of audio.

3. Sentence-Level Independence

Instead of generating continuous audio where each token depends on the entire history, Soprano splits text into sentences and generates each independently. This allows for massive batching on long-form content, generate 100 sentences in parallel, stitch them together, and you’ve just achieved 100x speedup through embarrassingly parallel computation.

The theoretical downside is that prosody and intonation can’t carry across sentence boundaries. In practice, the author notes this cross-sentence influence “doesn’t really happen anyway” in most TTS architectures, making it a free optimization.

The Stability Crisis Nobody’s Talking About

Here’s where the controversy ignites. Early adopters on the r/LocalLLaMA subreddit quickly discovered that Soprano’s speed comes with a reliability cost. One user reported that the model “chokes on ‘vocoder’ and other uncommon words,” producing slurred speech, noise, and repetition artifacts. When pushing the Hugging Face demo to generate longer content, quality degrades significantly after the one-minute mark.

The author acknowledges these issues, attributing them to the limited 1,000-hour training dataset. The recommended workaround? Regenerate broken sentences individually and tweak the temperature. For a model marketed on its streaming capabilities, where you don’t know the full text in advance, this manual retry loop is a architectural contradiction.

This reveals the first uncomfortable truth: the TTS field has been so obsessed with mean opinion score (MOS) and perceptual quality that it’s forgotten about robustness. Soprano’s instability on edge cases isn’t a unique flaw, it’s just the first model fast enough for users to encounter these failures at scale. When your TTS takes 10 seconds to generate a sentence, you don’t notice occasional glitches. When it generates 10 hours in 20 seconds, every artifact becomes painfully obvious.

The Fine-Tuning Revolt

The community’s immediate response to Soprano’s release wasn’t praise for the speed, it was a collective demand for training code. Within hours, the top Reddit comments were asking when fine-tuning would be available, with users pointing out that Kokoro-82M, the previous lightweight champion, also lacks public training scripts.

The underlying frustration is clear: researchers are tired of black-box models that can’t be adapted to their domains. A medical device company can’t deploy Soprano for patient instructions if it mispronounces drug names. A game studio can’t use it for character dialogue if it stumbles on fantasy vocabulary. The speed is meaningless without the ability to specialize.

The author has promised to release training code “if there is enough popular demand”, which itself is controversial. In 2025, withholding training code for an Apache 2.0 model feels like publishing a cookbook but keeping the oven instructions secret. The community’s reaction suggests a growing expectation that open-source AI must mean open-source training, not just inference.

The Kokoro Comparison That Stings

Soprano’s speed claims look particularly damning when compared to Kokoro-82M, a similarly sized model that achieves “only” 50-100x RTF on an RTX 3090. One user asked pointedly: “Using what hardware? With Kokoro-82M, I was seeing an RTF of closer to 50x or 100x.”

The author’s response, that Soprano’s efficiency comes from batching and long-form optimization, reveals a second uncomfortable truth: most TTS benchmarks are measuring the wrong thing. Kokoro’s 50x RTF might be on short, single-sentence inference. Soprano’s 2000x figure requires generating entire books. The model is architected to fill GPU memory and parallelize across sentences, making it blazing fast for bulk generation but potentially no better than Kokoro for single-sentence streaming.

This exposes a benchmark gaming problem that plagues AI research. Are we optimizing for user-facing latency, or for batch processing throughput? For interactive chatbots, the <15ms first-chunk latency matters more than the 2000x RTF. For audiobook generation, the opposite is true. Soprano’s numbers conflate these metrics, making direct comparisons misleading.

The 32 kHz Trap

Soprano’s claim of “perceptually indistinguishable” 32 kHz audio from 44.1/48 kHz is technically accurate for speech, but it’s a deliberate marketing spin. The choice of 32 kHz over the more common 24 kHz is smart, it avoids the muffled “s” and “z” sounds that plague lower sample rates, but it’s still not true broadcast quality. For music or sound effects, the difference would be obvious.

More importantly, 32 kHz is the maximum that the Vocos architecture can efficiently generate. This isn’t a quality choice, it’s a constraint of the speed-optimized decoder. The model is literally designed to be just good enough for voice applications while maximizing throughput, which is fine for chatbots but disqualifies it for high-fidelity audio production.

The Real Controversy: What Should TTS Optimize For?

Soprano-80M’s release has sparked a debate that goes beyond technical specs. The model’s existence argues that we’ve reached a point where TTS quality is “good enough”, and the next frontier is speed and accessibility. Why generate speech at 10x real-time when you could do 2000x? Why require 24GB VRAM when 1GB suffices?

But the community’s reaction, demanding fine-tuning code, complaining about stability, comparing unfavorably to Kokoro on short-form generation, suggests the field isn’t ready to make that trade-off. We want our cake and to eat it too: the speed of Soprano with the robustness of models trained on 100,000 hours, the quality of diffusion decoders with the efficiency of vocoders, the openness of Apache 2.0 with the completeness of training scripts.

This tension exposes a deeper issue: TTS research has become a game of marginal improvements on established metrics, while ignoring the deployment realities that Soprano’s speed attempts to address. We celebrate a 0.1 MOS improvement but ignore the fact that most TTS systems are too slow for real-time applications. We publish papers on voice cloning but can’t reliably pronounce “vocoder.”

The Verdict for Practitioners

If you’re building a real-time voice chatbot that needs to generate responses on the fly, Soprano-80M is currently the only viable open-source option. The <15ms latency is a genuine breakthrough, and the Apache 2.0 license means you can deploy it commercially without restrictions.

But you must implement defensive generation strategies: break input into short sentences, monitor for artifacts, and have fallback logic to retry failed generations. The model works best when sentences are 2-15 seconds long, so architect your prompts accordingly. For uncommon words or technical jargon, pre-process them into phonetic spellings.

For audiobook or long-form generation, Soprano is a game-changer, if you can tolerate manual quality control. Generate in batches, listen for artifacts, and regenerate problematic sections. The 2000x speed means you can afford to be picky.

For voice cloning, multilingual support, or style transfer, look elsewhere. Soprano is explicitly optimized for speed, not flexibility. The author has a roadmap that includes these features, but they’re months away at best.

The Takeaway

Soprano-80M’s greatest achievement isn’t its speed, it’s that it forces the TTS community to confront its own priorities. The model proves that extreme performance gains are possible when you stop trying to be everything to everyone and focus on a specific deployment scenario (real-time English chatbots). The backlash proves that the community isn’t ready to accept those trade-offs.

The most likely outcome? Soprano’s architectural innovations, the Vocos decoder, the 15 token/sec codec, the sentence-level parallelism, will be absorbed into more robust models, giving us the best of both worlds. But that will take time, and in the meantime, we have a TTS model that’s simultaneously the most impressive and most frustrating release of 2025.

The question isn’t whether Soprano-80M is good enough for production. It’s whether the TTS field is honest enough about what “production-ready” actually means.