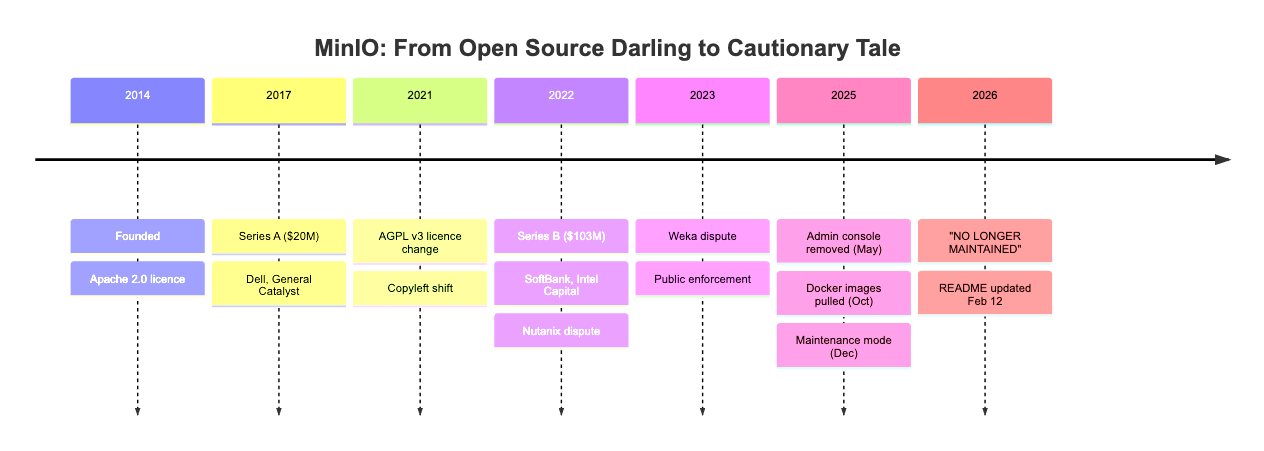

On February 12, 2026, the maintainers of MinIO posted six words that functioned as both eulogy and threat: THIS REPOSITORY IS NO LONGER MAINTAINED. The commit message directed users to AIStor, the commercial product with a $96,000 annual price tag. For a project that had amassed 60,000 GitHub stars and over a billion Docker pulls, the obituary was remarkably quiet. No press release, no blog post explaining the decision, just a README update in all caps and a link to the pricing page.

This wasn’t a sudden collapse. It was a methodical dismantling that began 18 months earlier, executed by a company valued at roughly $1 billion with $126.3 million in venture funding. The playbook MinIO followed wasn’t innovative, but the thoroughness was unprecedented. While other open core companies changed licenses and stopped, MinIO kept going, removing features, deleting binaries, and allegedly timing security disclosures to maximize commercial pressure.

The Trust Battery: How MinIO Charged It for a Decade

MinIO launched in 2014 with impeccable open source credentials. Founder Anand Babu Periasamy had previously built GlusterFS, which Red Hat acquired for $136 million. The pitch was simple: S3-compatible object storage you could run anywhere, written in Go, licensed under the permissive Apache 2.0. Companies could embed it, modify it, build products on top of it without legal headaches.

By 2019, MinIO had become the default self-hosted object storage for a generation of developers. Kubernetes clusters used it for persistent volumes. CI/CD pipelines stored artifacts in it. Machine learning teams staged terabytes of training data. The community didn’t just adopt MinIO, they evangelized it relentlessly on Stack Overflow, Reddit threads, and conference talks. That organic adoption took years to build and couldn’t be bought with marketing dollars.

The permissive licensing was the hook. It drove the billion Docker pulls that became the headline metric for investors. But metrics don’t pay back venture capital, revenue does.

The Series B Bargain: $103M for a License Change

In May 2021, eight months before closing its $103 million Series B led by SoftBank Vision Fund 2, MinIO made a critical move: it relicensed from Apache 2.0 to AGPL v3. The blog post framing the change claimed it was moving “toward” openness, which is technically true, AGPL is an OSI-approved license. But the practical effect was a legal tripwire.

AGPL’s network-use clause meant that companies running modified MinIO as a service had to make their source code available. For cloud providers and SaaS companies, this created a compliance burden that Apache 2.0 never imposed. Some purchased commercial licenses. Some started evaluating alternatives. And some, apparently, did neither, setting up the enforcement campaign that followed.

The funding sequence tells the story: license change first, then unicorn valuation. The community goodwill built over a decade became the collateral for a growth-stage investment from SoftBank, a firm not known for patience. When your valuation rests on adoption metrics, those metrics become a liability if they don’t convert to revenue.

The Enforcement Era: Public Shaming as a Sales Tool

MinIO didn’t just change the license, it weaponized it. In July 2022, the company published a blog post publicly accusing Nutanix of violating the AGPL in its Objects product. This wasn’t a quiet legal letter, it was a public shaming campaign that ended with Nutanix apologizing and coming into compliance. The message to the industry was clear: MinIO would enforce AGPL aggressively and in public.

The pattern repeated in March 2023 with Weka, a competing storage company. This time, Weka fought back with a detailed rebuttal disputing the technical basis of the claims. Legal analysts noted that some alleged violations predated the AGPL change and fell under the original Apache 2.0 license, which would have permitted the usage. The dispute settled quietly in mid-2024, but the damage was done.

The AGPL had become a sales tool. Companies comfortable running community MinIO under Apache 2.0 now faced a choice: pay for a commercial license, invest in AGPL compliance infrastructure, or migrate. For many, the math pointed toward migration, but first, they’d need a viable alternative.

The Dismantling: 2025’s Death by a Thousand Cuts

If the license change and enforcement were warning shots, 2025 was the artillery barrage. MinIO executed a systematic degradation of the community edition across multiple dimensions:

Feature Stripping: The Admin Console Vanishes

In early 2025, MinIO stripped the admin console and management GUI from the community edition via PR #3509. The full web interface that administrators relied on for years, bucket management, user administration, policy configuration, was replaced with a basic object browser. The stated rationale from Harshavardhana was resource constraints: maintaining separate consoles was “substantial.”

The community’s reaction was immediate and furious. A GitHub Discussion thread racked up 88 upvotes with comments like: “Minio handled this change in the worst possible way. No announcement before the release. No warning in the initial changelog. All tickets opened regarding this were closed and locked immediately.”

Jeffrey Paul, writing on sneak.berlin, was more direct: “Open core is not open source, regardless of what license they use. It’s what I’ve taken to calling ‘open source cosplay.’ They explicitly hobbled their ‘open source’ version to coerce people who don’t want to use their arcane CLI.”

The irony? Restoring the console required only reverting a submodule version. The code was always there, MinIO just turned it off.

Distribution Chokehold: Binaries Disappear

In October 2025, MinIO stopped publishing Docker images and pre-built binaries for the community edition. The Hacker News thread drew 733 points and 555 comments. The timing was suspicious: the binary removal coincided with a CVE disclosure, meaning users who needed to patch the vulnerability couldn’t simply pull an updated image. They had to build from source or migrate to AIStor.

One operator managing a 100-petabyte cluster noted that MinIO’s support pricing came in at “slightly less than the equivalent amount of S3 storage, not including actual hosting costs.” The message was clear: pay enterprise prices for the privilege of running your own hardware.

MinIO’s controversial shift in distribution strategy and community backlash created a trust crisis that rippled through cloud-native ecosystems. When a security vulnerability becomes a forcing function for commercial adoption, the social contract of open source is fundamentally broken.

Maintenance Mode: The Final Warning

On December 3, 2025, MinIO placed the community repository in “maintenance mode.” The Hacker News discussion hit 511 points and 322 comments. MinIO’s move to maintenance mode and its impact on open source contributions signaled that the project’s architectural foundation was no longer evolving.

Reddit’s r/selfhosted community warned users to avoid MinIO entirely, calling the changes a “trojan horse.” The consensus was forming: this wasn’t just a license change or feature restriction, it was a complete withdrawal from the open source social contract.

The Escalation Ladder: MinIO Goes Where Others Won’t

What makes MinIO’s trajectory unique isn’t any single decision, it’s the cumulative escalation. Other companies have changed licenses, MinIO climbed six levels of restriction that no other major open source company has attempted:

| Level | Action | MinIO | MongoDB | Elastic | HashiCorp | Redis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | License change (copyleft) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ||

| 2 | License change (source-available) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ||

| 3 | Feature stripping from community edition | ✅ | ||||

| 4 | Distribution restriction (Docker/binary removal) | ✅ | ||||

| 5 | Repository abandonment | ✅ | ||||

| 6 | Security leverage (CVE timing) | ✅ |

MongoDB stopped at Level 1. Elasticsearch went to Level 2 and actually reversed course in 2024, returning to AGPL. HashiCorp’s BSL change spawned OpenTofu. Redis’s license change launched Valkey with corporate backing.

MinIO is the only company that climbed all six levels. Every other company changed the rules, MinIO changed the rules, then removed the pieces from the board.

The Community’s Response: Fork It or Forget It

Open source communities are resilient, but they have long memories. The response to MinIO’s abandonment has been pragmatic and revealing.

The Alternatives Emerge

Several projects are positioning themselves as MinIO replacements, but notably, none are direct forks:

- SeaweedFS: Production-ready distributed file + object storage in Go

- Garage: Lightweight, geo-distributed object storage in Rust

- RustFS: Early-stage MinIO-inspired rewrite in Rust

- Ceph RADOS Gateway: Mature but complex full-featured solution

When Redis changed its license, the Linux Foundation launched Valkey as a direct fork with AWS, Google, and Oracle backing. When HashiCorp went to BSL, OpenTofu forked the last MPL-licensed version. MinIO’s AGPL licensing and complex codebase made a direct fork less attractive, so the community is rebuilding rather than forking.

The pgsty Fork: A One-Person Supply Chain

Vonng, founder of the Pigsty PostgreSQL distribution, took a different approach. Rather than wait for a foundation-backed fork, he simply did the work himself. The pgsty/minio fork demonstrates what’s possible when maintenance is treated as a supply chain problem rather than a feature development challenge:

- Restored the admin console by reverting the submodule version

- Rebuilt binary distribution with automated CI/CD for Docker images and Linux packages

- Resurrected community documentation on an independent site

The fork ships CVE-patched builds and promises bug fixes without new features. As Vonng notes, “MinIO as an S3-compatible object store is already feature-complete. It’s finished software. It doesn’t need more bells and whistles, it needs a stable, reliable, continuously available build.”

The Pattern: Open Core as Bait-and-Switch

MinIO’s saga reveals a playbook that has become depressingly familiar in infrastructure software:

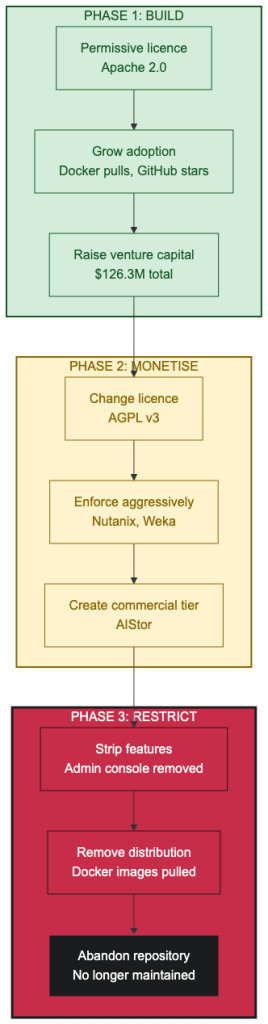

Phase 1: Build. Release under a permissive license. Grow adoption. Accumulate GitHub stars, Docker pulls, and community contributors. Use these metrics to raise venture capital.

Phase 2: Monetize. Change the license to something more restrictive. Create a commercial edition with premium features. Hire a sales team. Start converting free users to paid customers.

Phase 3: Restrict. If conversion rates disappoint (and they usually do, because free users chose the free version because it was free), start removing features from the community edition to widen the gap.

Most companies stop at Phase 2. MinIO went through Phase 3 and kept going into uncharted territory: pulling distribution channels, abandoning the repository, and allegedly timing security disclosures to coincide with commercial pressure.

The question isn’t whether open source companies can monetize. It’s whether the community will trust the next one that tries.

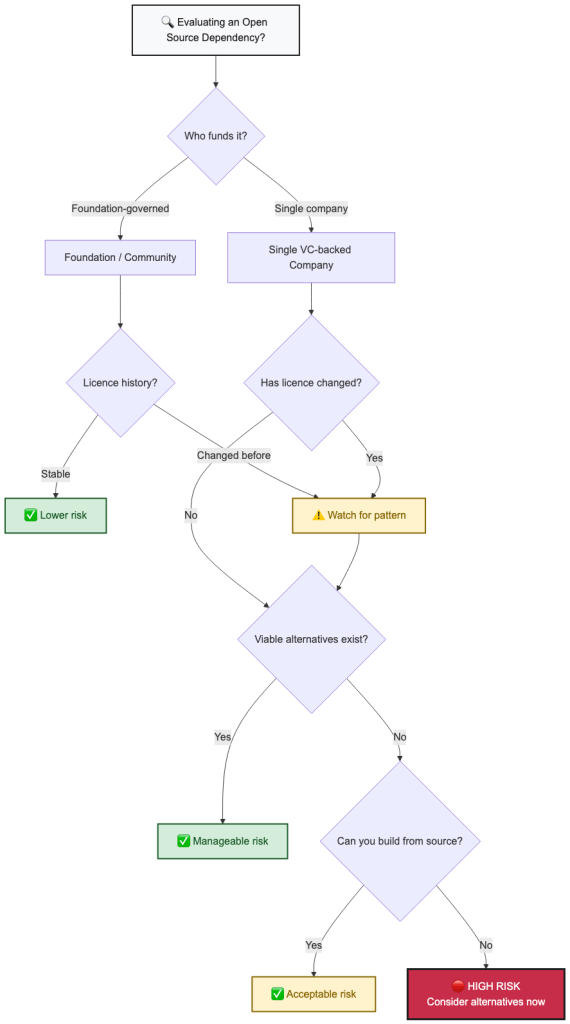

The Engineering Lessons: Trust, But Verify Your Dependencies

For engineering teams evaluating open source dependencies, MinIO provides a masterclass in what can go wrong:

License permissiveness is not a guarantee of continuity. Apache 2.0 didn’t prevent MinIO from changing to AGPL, stripping features, and abandoning the project. The license protects your right to use existing code, it doesn’t obligate anyone to keep developing it.

Adoption metrics can work against you. MinIO’s billion Docker pulls and 60,000 GitHub stars were used to raise $126 million. That capital came with growth expectations the community edition couldn’t satisfy. The very popularity that made MinIO valuable made it a target for monetization pressure.

Watch the cap table. When SoftBank Vision Fund 2 invests, the incentive structure shifts. Patient capital (foundations, strategic investors) aligns with long-term community health. Growth capital demands returns on a timeline that community goodwill can’t always deliver.

The CNCF badge isn’t a safety net. MinIO was a CNCF-associated project. That association didn’t prevent any of this. If your risk model assumes CNCF membership means stability, MinIO is your counterexample.

The Aftermath: A README in All Caps

MinIO’s community edition is dead. The company has made that unambiguous. What remains is AIStor, priced for enterprises, and a GitHub repository with a README in all caps.

Periasamy built GlusterFS and sold it to Red Hat for $136 million. The community continued under Red Hat’s stewardship. With MinIO, the community got a link to a pricing page.

That difference tells you everything about what changed between the two exits. The first time, the acquirer valued the community. This time, the company decided the community was the product, and they sold it to SoftBank.

For developers still running MinIO in production, the options are stark: migrate to AIStor and pay the toll, switch to an alternative like SeaweedFS or Garage, or trust the pgsty fork to maintain the supply chain. Each path carries risk, but the least risky decision is the one that should have been obvious from the start: never depend on a single company’s goodwill for your infrastructure.

The open source community has a long memory. The next time a project with tens of thousands of stars and a billion downloads starts tightening the screws, developers will remember the six words that ended MinIO’s open source chapter, and they’ll have their migration plans ready before the README changes.