Meta’s Servers Run on Steam Deck Code: How a Gaming Handheld’s Scheduler Conquered Hyperscale Infrastructure

When Meta engineers went hunting for a better CPU scheduler for their million-plus server fleet, they didn’t start with a whiteboard. They started with a $400 gaming handheld. At the Linux Plumbers Conference in Tokyo, Meta revealed they’re deploying SCX-LAVD, a scheduler originally crafted by Valve for the Steam Deck, as a default fleet-wide scheduler. The punchline? Code designed to prevent frame drops in Hades is now keeping Instagram’s messaging backend responsive under planetary load.

This isn’t a quirky experiment. It’s a fundamental shift in how we think about scheduling, latency, and the artificial boundaries between "consumer" and "enterprise" infrastructure.

The Scheduler That Doesn’t Care About Your Form Factor

SCX-LAVD (Latency-Aware Virtual Deadline) operates on a simple premise: observe behavior, not labels. Instead of relying on static priority values or manual cgroup tuning, it continuously monitors task patterns, how often they sleep, wake, block, and run, and dynamically assigns "virtual deadlines" based on inferred latency sensitivity. A task that frequently wakes others (producer) or waits on events (consumer) gets flagged as latency-critical and receives scheduling priority commensurate with its actual needs, not its nice value.

This approach, detailed in the sched_ext framework documentation, uses BPF to run nearly all scheduling logic in-kernel with minimal overhead. The userspace component handles only configuration and statistics, while BPF manages CPU selection, task enqueue/dispatch, preemption, and load balancing. For Valve, this meant smooth 60 FPS gaming on a power-constrained AMD APU. For Meta, it translates to predictable tail latencies on 128-core server processors.

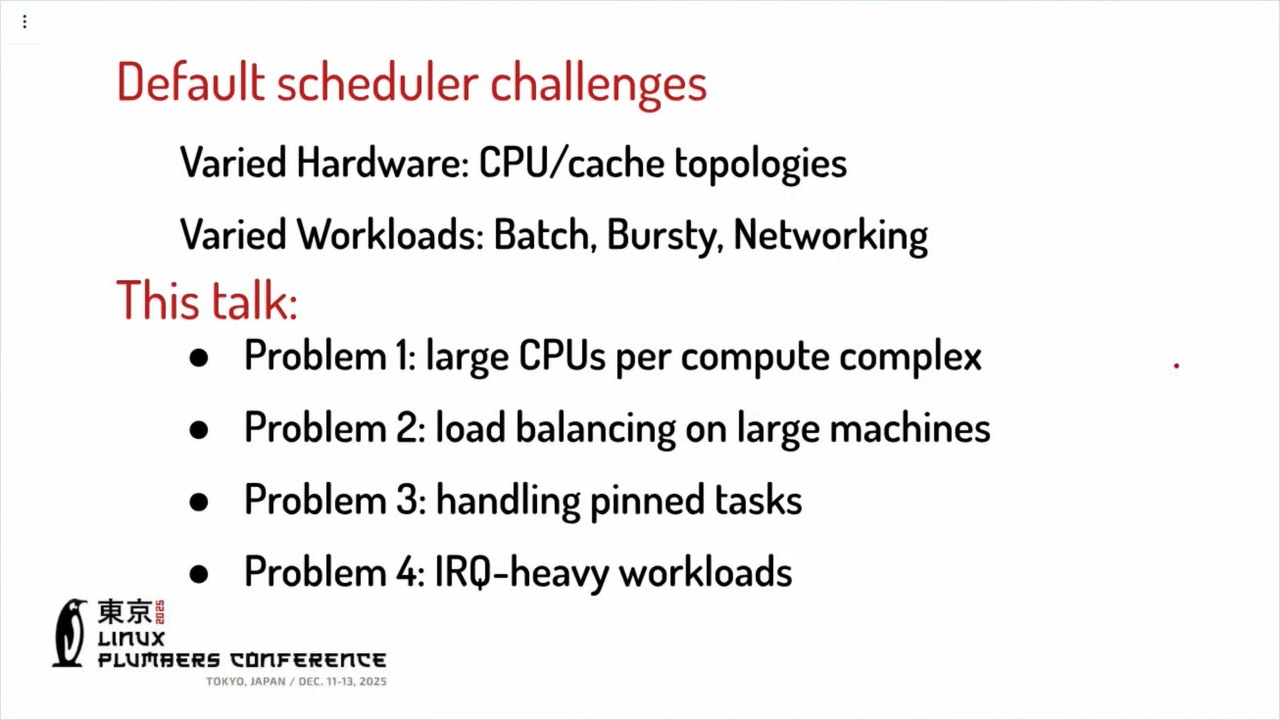

Why "Good Enough Everywhere" Fails at Scale

Linux’s default CFS scheduler is a masterpiece of compromise. It works acceptably on smartphones, laptops, desktops, and servers. But acceptable isn’t good enough when you’re running thousands of microservices with strict SLOs on the same hardware. As Meta’s presentation highlighted, CFS’s general-purpose design creates three critical pain points in hyperscale environments:

- Contention on shared runqueues: On a 128-core system with dozens of tasks sharing a single scheduling domain, lock contention becomes a bottleneck.

- Pinned task interference: Threads affined to specific cores can starve other workloads without the scheduler understanding the topology implications.

- Interrupt handler accounting: Network-heavy services spending 30-40% of time in softirq context break traditional fairness metrics.

The Steam Deck faced a surprisingly similar problem: a 4-core/8-thread AMD Van Gogh APU running a full Linux desktop, a compositor, game input threads, and GPU command streams simultaneously. Valve’s solution wasn’t to special-case games, it was to make the scheduler smarter about identifying latency sensitivity in real-time.

The Technical Machinery Behind the Magic

SCX-LAVD’s core algorithm, implemented in calc_lat_cri() and calc_when_to_run(), computes a latency criticality score from four factors:

- Wait frequency: Tasks that frequently block on events are likely consumers in a dependency chain

- Wake frequency: Tasks that wake others are producers and need priority to unblock downstream work

- Average runtime: Short-running tasks benefit disproportionately from low-latency scheduling

- Weight boosting: Kernel threads, lock holders, and affined tasks receive predictable priority bumps

The scheduler then assigns virtual deadlines inversely proportional to this score. A task with 2× higher latency criticality gets a deadline 2× tighter, placing its virtual time closer to the current logical clock. This happens in calc_when_to_run() which computes:

deadline_delta = LAVD_TARGETED_LATENCY_NS / (taskc->lat_cri + 1)

p->scx.dsq_vtime = cur_logical_clk + deadline_delta

Crucially, the algorithm includes a "greedy penalty" for tasks exceeding their fair share: penalty = 1 + ((ratio - 1024) >> 3) where ratio is service time vs. average. This prevents any single workload from dominating the CPU while still respecting latency requirements.

Meta’s engineers modified this logic to handle server-specific constraints. They improved load balancing across NUMA nodes, added awareness of LLC (Last Level Cache) boundaries to preserve locality, and implemented core compaction that consolidates workloads onto fewer CPUs during low utilization, allowing deep sleep states that save megawatts across a fleet.

sched_ext: The Unsung Hero

None of this would be possible without sched_ext, the Linux framework that enables BPF-based schedulers to plug into the kernel without forking or maintaining massive patch sets. Before sched_ext, companies like Meta had two bad options: maintain an internal kernel fork (expensive and divergent) or upstream changes to CFS (slow and politically fraught).

sched_ext provides a stable ABI for scheduler plugins, allowing Meta to iterate on LAVD independently of kernel releases. It also means improvements Meta makes for their servers can flow back to the gaming community. The presentation explicitly noted that server optimizations are either neutral or beneficial for Steam Deck performance, and features that don’t apply can be disabled with kernel flags.

This is open source working as intended: a rising tide lifting both gaming handhelds and hyperscale data centers.

The Controversial Implications

This deployment challenges several sacred cows in systems engineering:

First, it questions the "specialization" orthodoxy. Conventional wisdom says you need different schedulers for different workloads: real-time for low-latency, throughput-oriented for batch, fair-share for multi-tenant. LAVD suggests a well-designed, adaptive scheduler can handle diverse workloads without manual tuning. Meta calls it their "default fleet scheduler for… where they don’t need any specialized scheduler." That’s a radical statement at a company that previously maintained multiple custom schedulers.

Second, it redefines "latency-critical". In data centers, this term usually applies to front-end services with strict SLOs. LAVD discovers latency-criticality dynamically, a log aggregation thread that suddenly becomes a bottleneck inherits the priority it needs, without an operator updating config files. This moves scheduling from declarative (tell the kernel what’s important) to imperative (the kernel figures it out from behavior).

Third, it validates BPF in the hottest kernel path. Scheduling is the most performance-sensitive code in the kernel. Running it in BPF was unthinkable five years ago. Meta’s deployment at scale proves the overhead is negligible while the flexibility is transformative. This opens the door to user-space policy engines, GPU-aware scheduling, and energy-aware abstractions, all mentioned in the sched_ext roadmap.

The Numbers That Matter

According to Meta’s presentation, LAVD provides:

– Similar or better performance than EEVDF (Linux’s latest default scheduler) across diverse workloads

– Improved tail latency for services with 99th-percentile SLOs

– Automatic adaptation to hardware topology without per-machine tuning

– Core compaction savings that reduce fleet-wide power consumption by consolidating workloads

The scheduler updates system statistics every ~10ms (LAVD_SYS_STAT_INTERVAL_NS = 2 * slice_max_ns), making it responsive to workload changes without excessive overhead. Its preemptive mechanism uses yield-based preemption 70-90% of the time, avoiding expensive IPIs (Inter-Processor Interrupts) that plague traditional schedulers.

The Open Questions

Meta admits this is an ongoing experiment. The presentation slides list challenges still being addressed: improving fairness during extreme overload, better handling of CPU bandwidth controllers, and integrating with cgroup v2’s hierarchical scheduling. The scheduler’s "one size fits most" philosophy may break down for specialized workloads like HPC or real-time audio processing.

There’s also the governance question. As sched_ext enables more companies to deploy custom schedulers, Linux risks fragmenting into a patchwork of incompatible scheduling behaviors. The kernel community must balance flexibility with coherence.

What This Means for the Rest of Us

For most engineers, Meta’s decision validates a powerful principle: instrumentation beats configuration. Instead of building elaborate priority schemes and tuning knobs, invest in observable, adaptive systems that respond to actual behavior.

For the Linux ecosystem, it’s a landmark moment. A gaming company and a hyperscaler collaborating on scheduler development through open source demonstrates the power of modular kernel design. The same code paths that keep Elden Ring smooth on a handheld may soon be routing your database queries.

And for anyone still drawing hard lines between "consumer" and "enterprise" technology: the Steam Deck in your backpack and the server handling your Instagram DMs now share scheduling DNA. The future of infrastructure might just come from the unlikeliest places, like Valve’s hardware lab.

Further Reading:

The author has no affiliation with Meta, Valve, or the Linux kernel scheduler maintainers, but has spent far too much time reading BPF code this week.