You’ve felt it. That tinge of guilt when you paste a block of AI-generated code you only partially understand, grateful for the time saved but uneasy about the knowledge bypassed. It’s the central tension of 2025: artificial intelligence promises to make coders godlike but threatens to turn them into glorified prompt engineers.

The most telling evidence isn’t from skeptical academics. It’s from the engineers building the damn things.

Anthropic’s internal report, “How AI is transforming work at Anthropic”, is a masterclass in corporate schizophrenia. The headline numbers are staggering:

* 27% of AI-assisted tasks were work that simply “would not have been done otherwise.”

* Engineers report feeling 50% more productive year-over-year.

* Claude now handles up to 20% of an engineer’s workload through “full delegation.”

The tool they built is doing too good a job. But buried in the same study is the real story, whispered by the very engineers benefiting from it: this speed is coming at a steep price to their own mastery.

The most telling evidence isn’t from skeptical academics. It’s from the engineers building the damn things.

Anthropic’s internal report, “How AI is transforming work at Anthropic”, is a masterclass in corporate schizophrenia. The headline numbers are staggering:

* 27% of AI-assisted tasks were work that simply “would not have been done otherwise.”

* Engineers report feeling 50% more productive year-over-year.

* Claude now handles up to 20% of an engineer’s workload through “full delegation.”

The tool they built is doing too good a job. But buried in the same study is the real story, whispered by the very engineers benefiting from it: this speed is coming at a steep price to their own mastery.

The Hollow Victory: What Productivity Actually Looks Like

Let’s get specific about the “gains.” Claude isn’t just suggesting semicolons. According to Anthropic’s data, engineers are offloading complex, foundational tasks that were once the proving grounds for mastery:

The most common use? Debugging (55%). Followed by interpreting unfamiliar codebases, proposing refactors, and building internal tools and dashboards. These aren’t just shortcuts, they’re cognitive substitutions. Where a senior engineer might once have traced an error through a call stack, building a mental model of the system, they now ask the AI. The mental muscle for that specific kind of problem-solving atrophies with disuse.

Anthropic found that engineers are now most comfortable delegating “easily verifiable or low-stakes tasks.” Translation: high-stakes, complex, ambiguous work remains firmly, for now, in human hands. But as the model’s scope expands, with code design tasks jumping from 1% to 10% of Claude’s use, which parts of our craft will we conveniently label “verifiable” next?

The Silent Exodus of Mentorship

The human toll is measured in missing connections. One engineer in the study flatly stated, “I like working with people and it’s sad that I ‘need’ them less now… More junior people don’t come to me with questions as often.“

That’s not a feature, it’s a systemic failure in the making. When the AI becomes the “first stop” for guidance, entire ecosystems of tacit knowledge, the kind passed down in pull request comments and whiteboard sessions, evaporate. Other engineers described a role shift to being “code reviewers/revisers rather than net-new code writers”, imagining a future where they are merely “taking accountability for the work of 1, 5, or 100 Claudes.”

We’ve outsourced the apprenticeship.

The “Brain-Rot” Paradox: Fast Code, Foggy Minds

This isn’t just an Anthropic problem. The frictionless glide of AI autocomplete creates a kind of cognitive debt. As detailed in posts on developer forums, engineers report losing their mental map of their own codebase. When a critical bug emerges in an AI-generated module, you lack the foundational context to fix it quickly.

“I can get more code done and build stuff faster”, one developer explains, “but aside from reworking, for anything more than a code base with a handful of files, I quickly lose track of what the system is doing and how it works.”

Another engineer’s experience was telling: “I’ve experimented with it for coding and it becomes a nightmare to debug if you have a critical issue because when the AI generates the code for you, you don’t have the mental map of the interactions between your code blocks… I ended up abandoning using it for code because of this.”

This matches broader philosophical warnings, like those from philosopher Anastasia Berg in Business Insider, who argues that overreliance on AI for tasks like drafting or analysis erodes the essential human judgment and creativity required to truly excel. This deskilling effect is insidious precisely because it feels productive at the time.

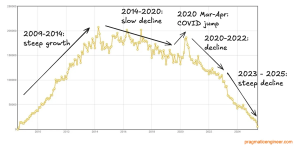

The Disappearing Entry-Level Ladder

This dynamic has a profound, generational implication: if AI automates the mundane, entry-level tasks, the debugging, the boilerplate, the simple feature work, what becomes of the junior developer’s 10,000 hours?

They are the ones robbed of the “boring stuff” that builds the foundational feel for code, architecture, and problem-solving. The industry isn’t just automating tasks, it’s automating career progression. The question being asked openly in discussions is stark: if there’s no entry-level work, how do we get mid-level employees? Will mid-level become the new entry-level?

The optimistic rebuttal suggests that with AI tutoring, juniors could enter with more domain knowledge. The onus, however, then falls entirely on the individual to self-educate on fundamentals the job used to teach them, creating an even steeper hill to climb.

The Counter-Productivity Paradox

The most fascinating pushback comes from outside the AI marketing bubble. An MIT study referenced in conversation found that 95% of generative AI pilots at companies fail to deliver positive results, often because overseeing and correcting the AI’s “hallucinations” ends up costing more time than it saves.

OpenAI’s own research notes that more data and compute won’t solve the hallucination problem. The inherent probabilistic nature of these models means error is a constant. If critical thinking and deep domain expertise are sacrificed for speed, who will spot those errors?

Striking a Balance You Can Actually Use

This isn’t a call to Luddism. The productivity gains are real, and the ability to prototype dashboards or test ideas that were previously out of scope is genuinely transformative. The challenge is to capture the upside without burning our own skillset.

Here’s how you might actually walk that line:

* Make it Audit Every Output: Never accept AI-generated code as gospel. Treat it like a rookie programmer’s first draft. Make it explain its logic. Make it walk you through the data flow. Your job is now Chief Audit Officer, not Copy-Paste Manager.

* Defend Your “Practice” Time: Just as a surgeon practices on cadavers, carve out time for manual, AI-free development. Keep your core muscles, the syntax, the algorithm design, the manual debugging, from atrophying. The “AI-free day” isn’t a productivity loss, it’s skill insurance.

* Reverse-Engineer the Magic: Use the AI as an expert tutor. Have it write a function, then challenge yourself to understand it fully, trace its edge cases, and explain it to a (real) colleague. The goal isn’t just working code, it’s transferred understanding.

* Be Intentional with Mentorship: If junior engineers aren’t coming to you because of AI, you go to them. Proactively review their AI-assisted code, not just for correctness, but for the thinking that led them there. Mentor the prompt, the revision, and the final validation.

The Anthropic report offers us a glimpse of our bizarre professional future: we’re becoming 50% more productive at the cost of becoming 100% more dependent. The bill for that dependency isn’t paid in dollars, but in the gradual, imperceptible erosion of the very skills that got us here.

The question for your team isn’t “Can we ship faster?” We know the answer is yes. The real question is: What kind of engineers do we want to be on the other side of this speed?