Why Big Software Projects Still Fail Despite Trillions Spent: A System Design Crisis

The statistics should be impossible: global IT spending has more than tripled since 2005, from $1.7 trillion to $5.6 trillion in constant 2025 dollars, yet software success rates haven’t improved. As Robert N. Charette notes in his IEEE Spectrum analysis, “despite additional spending, software success rates have not markedly improved in the past two decades.” This isn’t just about wasted money, it’s about a fundamental crisis in how we approach system design at scale. We’re pouring resources into projects that collapse under their own complexity, leaving financial carnage and human wreckage in their wake.

The Illusion of Scale: When Bigger Means Worse

The problem isn’t that we don’t know how to build software, it’s that we haven’t adapted our methodologies for the scale and complexity we’re now attempting. According to the Consortium for Information & Software Quality (CISQ), the annual cost of operational software failures in the United States in 2022 alone reached $1.81 trillion, with another $260 billion spent on software-development failures. That’s larger than the entire U.S. defense budget for that year.

What makes this especially galling is that we’re not dealing with novel problems. Charette observes that “uncovering a software system failure that has gone off the rails in a unique, previously undocumented manner would be surprising because the overwhelming majority of software-related failures involve avoidable, known failure-inducing factors documented in hundreds of after-action reports, academic studies, and technical and management books for decades.”

Case Study: The Phoenix Payroll Debacle

Consider the Canadian government’s CA $310 million Phoenix payroll system, which went live in April 2016 and immediately imploded. Project executives believed they could deliver a modernized payment system customizing PeopleSoft’s off-the-shelf payroll package to follow 80,000 pay rules spanning 105 collective agreements with federal public-service unions, while implementing 34 human-resource system interfaces across 101 government agencies.

Their strategy for success? According to subsequent audits, they planned to “save by removing or deferring critical payroll functions, reducing system and integration testing, decreasing the number of contractors and government staff working on the project, and forgoing vital pilot testing.” The result: over nine years, around 70 percent of the 430,000 current and former Canadian federal government employees paid through Phoenix have endured paycheck errors. Even as recently as fiscal year 2023, 2024, a third of all employees experienced paycheck mistakes.

The ongoing financial costs to Canadian taxpayers have climbed to over CA $5.1 billion ($3.6 billion USD), with the government acknowledging that replacing Phoenix will cost “several hundred million dollars more and take years to implement.” The late Canadian Auditor General Michael Ferguson’s audit reports described the effort as an “incomprehensible failure of project management and oversight.”

The Organizational Memory Gap

The most frustrating aspect of these failures is that organizations repeatedly make the same mistakes. Charette notes that Phoenix “was the government’s second payroll-system replacement attempt, the first effort ending in failure in 1995. Phoenix project managers ignored the well-documented reasons for the first failure because they claimed its lessons were not applicable.” This pattern of institutional amnesia plagues large organizations across sectors.

What’s driving this pattern? According to Stephen Andriole, chair of business technology at Villanova University’s School of Business, the core issues fall into three categories:

- Technical issues: Over-engineering, insufficient technical review, poor architectural decisions

- Management issues: Unrealistic schedules, insufficient resources, inadequate planning

- Business issues: Unclear requirements, scope creep, lack of executive sponsorship

The problem isn’t that we don’t know what goes wrong, it’s that we consistently underestimate the difficulty of coordinating across these domains.

The U.K. Post Office Horizon Scandal: When Software Kills

If Phoenix represents financial carnage, the U.K. Post Office’s Horizon system represents human tragedy. Rolled out in 1999 and provided by Fujitsu, Horizon was “riddled with internal software errors that were deliberately hidden”, leading to the Post Office unfairly accusing 3,500 local post branch managers of false accounting, fraud, and theft. Approximately 900 of these managers were convicted, with 236 incarcerated between 1999 and 2015.

The technical failures were compounded by organizational ones: “There were ineffective or missing development and project management processes, inadequate testing, and a lack of skilled professional, technical, and managerial personnel.” Worse still, “the Post Office’s senior leadership repeatedly stated that the Horizon software was fully reliable, becoming hostile toward postmasters who questioned it.”

Nearly 350 of the accused died before receiving any payments for the injustices experienced, with at least 13 believed to be by suicide. Despite two failed replacement attempts in 2016 and 2021, the Post Office continues using Horizon while planning to spend £410 million on a new system.

The Microservices Mirage and Agile Illusions

Many organizations have turned to modern development methodologies as potential saviors, but the results remain mixed. While Agile and DevOps “have proved successful for many organizations, they also have their share of controversy and pushback.” Some reports claim Agile projects have a failure rate of up to 65 percent, while others claim up to 90 percent of DevOps initiatives fail to meet organizational expectations.

The fundamental issue isn’t the methodology itself but the organizational context. Charette notes that “successfully implementing Agile or DevOps methods takes consistent leadership, organizational discipline, patience, investment in training, and culture change. However, the same requirements have always been true when introducing any new software platform.”

Systemic Root Causes: Beyond Technology

The crisis in large-scale software projects stems from several systemic issues that transcend individual technologies or methodologies:

Requirements Architecture Failure

Most large projects suffer from what Charette calls “failures of human imagination, unrealistic or unarticulated project goals.” The Phoenix system attempted to navigate 80,000 pay rules, an inherently unmanageable level of complexity that should have triggered architectural red flags from the beginning.

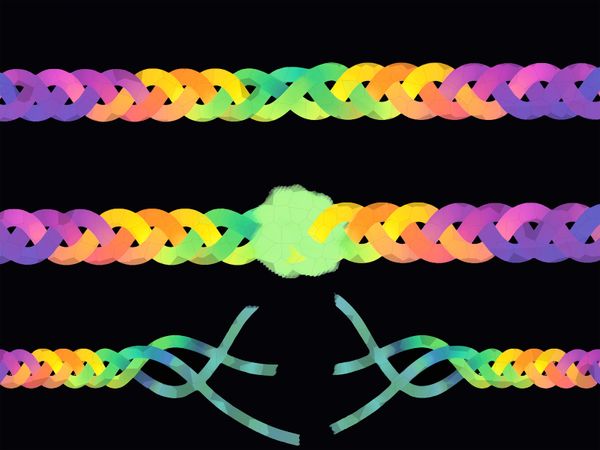

Modularity Breakdown

Well-designed projects “usually consist of a hierarchy of different units, each with a single, clear, and specific responsibility”, as noted in software architecture best practices. Yet large projects consistently violate this principle, creating monolithic systems where failure in one component cascades through the entire architecture.

Organizational Scaling Limits

There appears to be a fundamental limit to how effectively large organizations can coordinate software development. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program demonstrates this perfectly: “Software and hardware issues with the F-35 Block 4 upgrade continue unabated. The Block 4 upgrade program which started in 2018, and is intended to increase the lethality of the aircraft has slipped to 2031 at earliest from 2026, with cost rising from $10.5b to a minimum of $16.5b.”

The AI Solution That Isn’t Coming

Many hope AI tools and coding copilots will rescue large-scale IT projects, but Charette offers a sobering reality check: “For the foreseeable future, there are hard limits on what AI can bring to the table in controlling and managing the myriad intersections and trade-offs among systems engineering, project, financial, and business management, and especially the organizational politics involved in any large-scale software project.”

The problem isn’t technical capability, it’s that “few IT projects are displays of rational decision-making from which AI can or should learn. As software practitioners know, IT projects suffer from enough management hallucinations and delusions without AI adding to them.”

The Way Forward: Accountability Over Methodology

What separates successful large-scale projects from failures isn’t methodology but accountability. Charette notes that “it is extremely difficult to find software projects managed professionally that still failed. Finding examples of what could be termed ‘IT heroic failures’ is like Diogenes seeking one honest man.”

Honest Risk Accounting

“Honesty begins with the forthright accounting of the myriad of risks involved in any IT endeavor, not their rationalization. It is a common ‘secret’ that it is far easier to get funding to fix a troubled software development effort than to ask for what is required up front to address the risks involved.”

Human-Centered System Design

Just as the AI community advocates for “human-centered AI”, we need human-centered software development that “means trying to anticipate where and when systems can go wrong, move to eliminate these situations, and build in ways to mitigate the effects if they do happen.”

Professional Accountability

Some argue it’s time for software liability laws or for IT professionals to be licensed like other professionals. While neither is likely to happen soon, the principle remains valid: we need mechanisms that ensure consequences for repeated, predictable failures.

Breaking the Cycle

The key insight from two decades of software failure analysis is that we’re not dealing with technical problems but human and organizational ones. As Charette paraphrases Roman orator Cicero: “Anyone can make a mistake, but only an idiot persists in his error.”

Until organizations develop the institutional courage to confront the actual complexity of large-scale software development, rather than pretending it can be managed away with the latest methodology or technology, we’ll continue seeing the same patterns repeat. The $10+ trillion question isn’t how to build better software, but how to build organizations capable of managing the complexity they’re creating.

The solution starts with acknowledging that software at scale behaves differently than software in small teams. It requires different governance, different risk models, and different success criteria. Most importantly, it requires the humility to recognize that some problems might simply be too complex to solve with our current approaches, and that sometimes, the most responsible engineering decision is to scale back ambitions rather than guarantee failure.