The most expensive operation in LLM inference isn’t always the matrix multiplications or attention calculations. Sometimes it’s the humble Top-K sampling, that final step where the model selects the next token from a vocabulary of 32,000 to 256,000 candidates. PyTorch’s CPU implementation has been the de facto standard, quietly chugging along while GPUs hog the optimization spotlight. That changed when a new open-source implementation dropped, claiming up to 20x speedup using nothing more than clever algorithm design and AVX2 instructions.

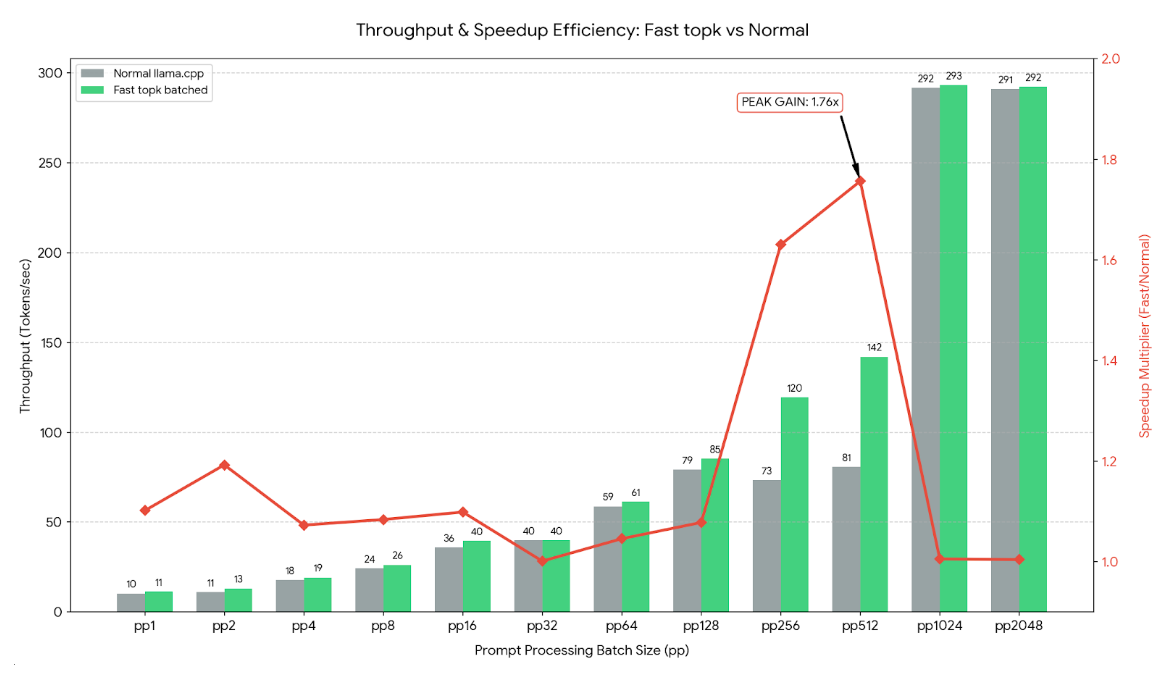

The numbers are hard to ignore. For a vocabulary size of 256,000 and K=50, the optimized implementation clocks in at 0.079ms versus PyTorch’s 1.56ms, a 20x improvement. Even at smaller vocab sizes, the gains remain substantial: 13x faster at 128K vocabulary and 4x faster at 32K. The real kicker? When integrated into llama.cpp, prompt processing on a 120B MoE model jumped from 81 to 142 tokens per second, a 63% improvement that translates directly to lower latency and higher throughput for real applications.

Why Top-K Sampling Matters More Than You Think

Top-K sampling is the gatekeeper between raw model outputs and coherent text generation. After the model produces logits for every token in its vocabulary, Top-K selects the K most likely candidates, enabling downstream sampling techniques like temperature scaling and nucleus sampling. It’s a sequential bottleneck: every token generation requires a full scan, sort, or selection operation across tens or hundreds of thousands of values.

Traditional implementations treat this as a straightforward algorithmic problem. Use a min-heap to maintain the top K elements, insert each new element one by one, and pay the O(N log K) cost. For a 128K vocabulary and K=50, that’s thousands of heap operations per token. Multiply by batch processing and long generation runs, and the overhead compounds into measurable latency.

The breakthrough realization: modern CPUs can compare eight 32-bit floats simultaneously with AVX2 instructions, yet most implementations leave this capability dormant. Worse, they make no assumptions about input distributions, missing opportunities to short-circuit work when data is already sorted or nearly constant.

The AVX2 Implementation: Speed Through Smarter Work, Not Just More Compute

The core innovation combines four optimization strategies into a single-pass algorithm that rarely needs to examine every element.

First, adaptive sampling estimates a threshold by scanning the first thousand elements. Instead of carefully maintaining a sorted structure, the algorithm asks a simpler question: “Is this value above my estimated threshold?” This reduces the problem from precise tracking to approximate filtering, which SIMD instructions handle beautifully.

Second, AVX2 SIMD processes eight floats in parallel. The implementation uses _mm256_cmp_ps for vectorized comparisons and _mm256_max_ps for parallel max-finding, effectively giving the CPU an eight-wide execution unit for this workload. On modern x86 processors, this alone delivers a theoretical 8x speedup over scalar code.

Third, cache-optimized block scanning structures memory access to exploit prefetching. While the current block is processed, the next block is fetched into cache, hiding memory latency. For large vocabularies that don’t fit in L1 cache, this prevents the algorithm from being memory-bound.

Fourth, fast paths for sorted and constant inputs bypass the general algorithm entirely. In practice, model logits often exhibit structure, early tokens may be sorted, or certain positions may hold constant values. Detecting these patterns early saves massive computation.

The implementation is available on GitHub at RAZZULLIX/fast_topk_batched, with pre-built DLLs for Windows and build instructions for Linux/macOS.

Benchmark Reality Check: When Theory Meets Silicon

The performance claims hold up across vocabulary sizes and batch configurations. For single-batch inference, the common case in interactive applications, the latency numbers tell a clear story:

| Vocabulary Size | Fast TopK (ms) | PyTorch CPU (ms) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32K | 0.043 | 0.173 | 4x |

| 128K | 0.057 | 0.777 | 13x |

| 256K | 0.079 | 1.56 | 20x |

Even at batch=64, where memory bandwidth pressure increases, the implementation maintains its advantage: 2.10ms versus PyTorch’s 7.16ms for 128K vocabulary. The gap narrows against PyTorch CUDA (0.086ms single-batch, 0.375ms batch-64), but the fact that a CPU implementation can be competitive with CUDA for small batches challenges the assumption that sampling must happen on GPU.

The llama.cpp integration demonstrates real-world impact beyond microbenchmarks. Processing a 512-token prompt on a 120B MoE model improved from 81 tokens/second to 142 tokens/second, a 63% gain that directly reduces time-to-first-token, arguably the most important latency metric for user-facing applications.

The Controversy: Is This Actually Useful?

Not everyone is convinced. Skepticism on developer forums centers on three points: hardware assumptions, framework integration, and the rise of fused kernels.

The AVX2 requirement limits deployment to relatively modern x86 CPUs. ARM processors, common in edge devices and Apple Silicon, see no benefit. Even within x86, AVX2 support varies, though it’s been standard since Intel Haswell (2013) and AMD Excavator (2015).

A more fundamental critique questions whether Top-K on CPU is even the right problem. Most inference frameworks keep logits in GPU memory, using fused sampling kernels that never materialize the full logits tensor in CPU-accessible memory. Moving data from GPU to CPU just for sampling introduces PCIe transfer overhead that could swamp the algorithmic speedup. The llama.cpp integration sidesteps this by operating where the data already lives, on CPU for CPU inference paths, but that narrows the applicability.

The implementation’s author acknowledges these limitations while maintaining that CPU inference remains relevant for edge deployments, cost-sensitive applications, and hybrid approaches where GPU memory is constrained.

Building and Using: From GitHub to Production

Getting started requires minimal setup. For Windows, compile with aggressive optimizations:

gcc -shared -O3 -march=native -mtune=native -flto -ffast-math -funroll-loops -finline-functions -fomit-frame-pointer -static -static-libgcc fast_topk_batched.c -o fast_topk_batched.dll -lwinmmLinux and macOS builds follow a similar pattern, producing a shared library:

gcc -shared -fPIC -O3 -march=native -mtune=native -flto -ffast-math -funroll-loops -finline-functions -fomit-frame-pointer fast_topk_batched.c -o libfast_topk.soPython integration uses ctypes:

import ctypes

import numpy as np

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./libfast_topk.so')

lib.fast_topk_batched.argtypes = [

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float),

ctypes.c_int, ctypes.c_int, ctypes.c_int,

ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_int)

]

# Process batch_size=16, vocab_size=128000, k=50

logits = np.random.randn(16, 128000).astype(np.float32)

indices = np.zeros(16 * 50, dtype=np.int32)

lib.fast_topk_batched(

logits.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_float)),

16, 128000, 50,

indices.ctypes.data_as(ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c_int))

)

indices = indices.reshape(16, 50) # Top-50 indices per sequenceThe llama.cpp example modifies llama-sampling.cpp to replace the default Top-K routine, requiring only that the DLL be placed in the source directory.

Beyond Top-K: What This Means for LLM Inference

This optimization matters beyond the immediate speedup. It represents a shift in how we think about inference bottlenecks. While the industry chases faster GPUs and lower-bit quantization, significant gains hide in plain sight within algorithmic improvements. The 20x speedup didn’t require new hardware, custom silicon, or exotic data types, just better use of existing CPU capabilities.

The controversy around real-world applicability actually strengthens the point. The fact that we’re debating whether CPU-based Top-K is relevant exposes how tightly coupled our mental models are to GPU-centric workflows. As models grow larger and memory constraints tighten, hybrid CPU-GPU approaches become more attractive. Having a CPU implementation that doesn’t sacrifice performance enables new architectural patterns: keep the heavy lifting on GPU, but move sampling and other post-processing to CPU where appropriate.

For the broader ecosystem, this sets a new baseline. Framework maintainers now have a reference implementation that demonstrates what’s possible. PyTorch’s CPU Top-K, long considered “good enough”, faces a credible open-source alternative that forces a reckoning. Either PyTorch adapts, or users seeking maximum CPU performance have a clear alternative.

The 63% improvement in llama.cpp isn’t just a number, it’s a glimpse into a future where inference optimization happens at every layer of the stack, from matrix multiplications to token sampling, leaving no performance on the table.