The Scaling Mindset Gap: What Senior Engineers Actually Do When Systems Start to Sweat

Most developers can build features that work perfectly in staging. The real test comes when actual users show up, traffic spikes at 2 AM, and your beautiful monolith starts gasping for breath. That’s when the gap between junior and senior thinking becomes expensive.

The prevailing wisdom on developer forums suggests that 90% of scalability problems come down to database optimization. There’s truth in that, but it’s also the kind of simplification that leads teams to optimize the wrong things at the wrong time. The real skill isn’t just knowing what to optimize, it’s knowing whether you need to optimize at all.

The 90% Trap: When Database Queries Are Your Red Herring

Senior engineers understand that scalability isn’t a single target. There’s a massive difference between handling thousands of requests per second and millions. A well-tuned PostgreSQL instance can easily serve thousands of queries per second with proper indexing and connection pooling. But millions? That requires a completely different architecture, one that involves sharding, distributed caches, and accepting eventual consistency.

The trap is this: junior engineers often start building distributed systems when they should be tuning queries. Senior engineers do the opposite. They know that most software never reaches the scale where the web server becomes the bottleneck. A typical application with 25,000 users and maybe 1,000 concurrent connections doesn’t need Kubernetes or microservices, it needs tuning. That distinction saved their company $60,000 annually in cloud costs.

This isn’t just about cost. It’s about complexity. Every distributed system you add introduces new failure modes. A single database query can fail predictably. A distributed transaction across three microservices can fail in ways that require a PhD in chaos theory to debug.

The Scale Illusion: Knowing When “Good Enough” Actually Is

The system design interview industrial complex has created a generation of engineers who think every system needs to handle Netflix-scale traffic. The reality? Most applications will never see millions of requests per second. The median SaaS product peaks at a few thousand RPS.

Senior engineers have developed a nose for this. They can smell when a requirement is aspirational versus when it’s business-critical. They know that rethinking performance and cost at scale with local vs. cloud trade-offs isn’t just a technical decision, it’s a product decision. Sometimes the right answer is “we’ll deal with that when we have 10x the users”, not “let’s build for 100x just in case.”

This mindset shift is crucial. Premature optimization is still the root of all evil, but premature distribution is worse. It adds operational overhead, debugging complexity, and team coordination costs before you even know if your product has market fit.

The Ordered Approach: Why Seniors Don’t Jump to Kubernetes

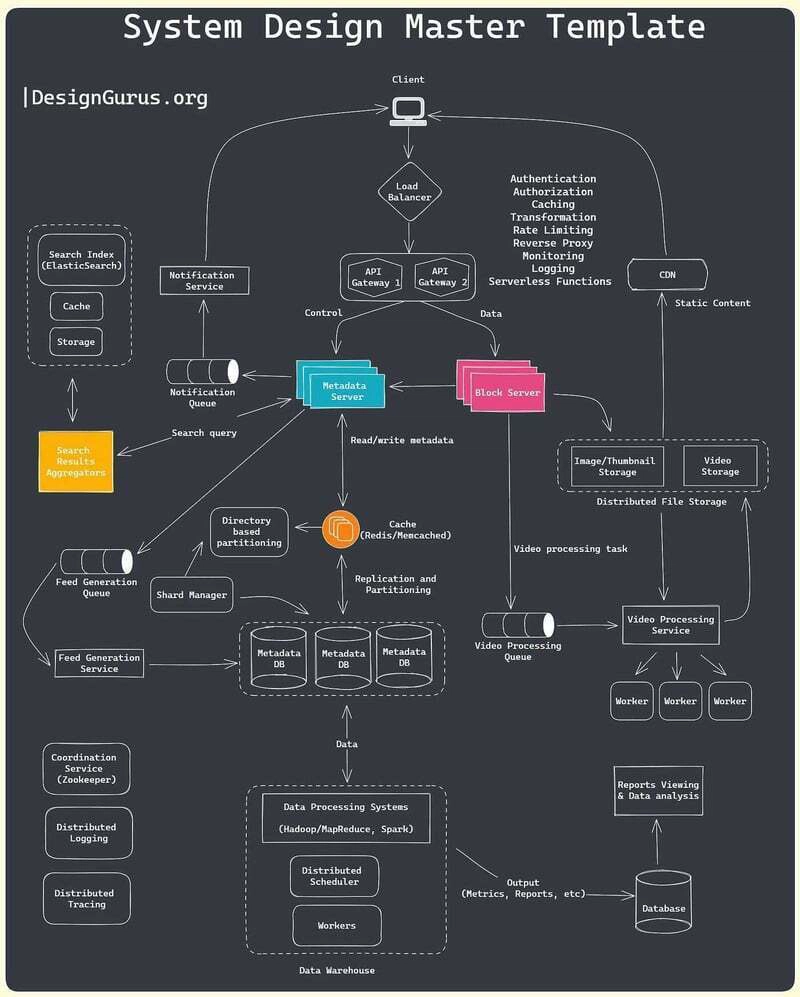

The Javarevisited guide nails this: scaling is about solving problems in order. You start with one server. You understand where it breaks. Then you decide whether to scale vertically (bigger server) or horizontally (more servers).

This sounds obvious, but watch any junior team facing performance issues. Their first instinct is to reach for the trendiest tool in their stack. RabbitMQ! Kafka! A service mesh! Seniors reach for EXPLAIN ANALYZE and iostat.

The ordered approach looks like this:

- Profile first: Where’s the actual bottleneck? Is it CPU-bound? I/O-bound? Memory-bound? Network-bound? One engineer noted that throwing more application servers at a database problem just means more connections hammering an already-overloaded database.

- Tune second: Can you fix it with indexing, query optimization, or caching? Redis for session storage and frequently accessed data can reduce database load by an order of magnitude. This is where the real 90% lives, not just in query optimization, but in architectural decisions about what to cache and for how long.

- Scale third: Only when you’ve proven that a single well-tuned instance can’t handle the load do you start distributing. And even then, you start with the simplest distribution model that works.

This approach requires patience and discipline, two qualities that separate seniors from juniors who are eager to put “Kubernetes experience” on their resume.

The Trade-off Matrix: Every Solution Moves Failures Around

Here’s a senior insight that rarely shows up in blog posts: when you eliminate a single point of failure (SPOF), you don’t eliminate failure. You just move it.

Add a load balancer in front of your app servers? Great, now your load balancer is the SPOF. Make it highly available? Now your database is the SPOF. Shard your database? Now your shard router is the SPOF.

Senior engineers think in terms of failure domains and blast radius. They know that real-world lessons in scaling systems architecture responsibly often involve accepting that some failures are more acceptable than others. A brief downtime during a failover beats data corruption every time.

This is where the CAP theorem stops being academic and starts being practical. You can’t have consistency, availability, and partition tolerance all at once. Most junior engineers choose consistency because it feels safer. Senior engineers choose based on the business impact: can we afford stale data? Can we afford downtime? The answer determines whether you optimize for read replicas, caching layers, or strong consistency models.

The Failure-First Mindset: Designing for the 2 AM Phone Call

The biggest mindset shift is this: junior engineers design for the happy path. Senior engineers design for the failure path.

When a senior architect looks at a system diagram, they’re not seeing how it works. They’re seeing how it breaks. They assume:

– Machines will crash

– Networks will lag

– Databases will get overloaded

– Dependencies will time out

– Users will do things you never imagined

This isn’t pessimism, it’s engineering. Every assumption becomes a test case. Every dependency becomes a circuit breaker. Every database query becomes a candidate for caching or replication.

The result? Systems that degrade gracefully instead of collapsing catastrophically. A senior-designed e-commerce site might show slightly stale inventory counts during peak load instead of returning 500 errors. A junior-designed site might show perfect data or nothing at all.

The Cost Consciousness: When $60K in Savings Is Just the Start

That $60,000 annual savings from right-sizing a 25k-user system? That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Senior engineers think about cost as a primary design constraint, not an afterthought.

They know that cost optimization and architectural trade-offs in CI/CD at scale can free up engineering time for features instead of infrastructure babysitting. They understand that every auto-scaling group, every managed service, every multi-AZ deployment has a dollar amount attached, and that amount directly impacts the company’s ability to hire, market, and grow.

This is perhaps the most underrated senior skill: the ability to have a conversation with finance about why spending $5k/month on a managed database beats paying one engineer $15k/month to maintain PostgreSQL. Or conversely, why a single well-tuned server at $500/month is smarter than a microservices architecture that costs $5k/month before you factor in the engineering overhead.

The Learning Loop: Why Seniors Still Read the Manual

There’s a paradox in senior engineering: the more you know, the more you realize you don’t know. That’s why senior engineers devour resources like the ByteByteGo system design courses and read books like Designing Data-Intensive Applications, not because they need to learn what a load balancer is, but because they need to understand the edge cases, the failure modes, the subtle trade-offs that only come from seeing hundreds of systems in production.

They know that the difference between a good architecture and a great one often comes down to handling that one weird edge case that happens 0.1% of the time but impacts 10% of your revenue. You don’t learn those from tutorials. You learn them from experience, from reading case studies, and from having your own systems fail in ways you never imagined.

The Bottom Line: Judgment Over Knowledge

The gap between junior and senior engineers isn’t a gap in knowledge, it’s a gap in judgment. Seniors have seen enough systems fail to know that simplicity beats complexity. They’ve sat through enough post-mortems to know that most outages come from changes made with good intentions. They’ve paid enough cloud bills to know that scaling isn’t free.

This judgment manifests as:

– Patience: Not building distributed systems until you need them

– Skepticism: Questioning whether every feature needs real-time consistency

– Pragmatism: Choosing the boring technology that works over the exciting technology that might work

– Humility: Admitting that your system will fail and planning for it

The next time you’re sketching out an architecture, ask yourself: would a senior engineer build this, or would they spend a week tuning queries first? The answer might save you $60,000, and countless sleepless nights.