A developer recently unveiled a Postgres database manager that runs entirely in the browser, cramming ER diagrams, schema navigation, relationship exploration, and data quality auditing into a single standalone application. The kicker? Everything lives in local storage. No server, no backend, no infrastructure costs. The demo feels magical, click a table, and pivot tables materialize, hover over a column, and smart previews detect URLs, geographic coordinates, or color codes. It’s the kind of UX that makes traditional database GUIs feel archaic.

But here’s what the demo doesn’t show: the architecture is a time bomb. The moment you close the wrong browser tab, clear your cache, or try to collaborate with a teammate, the magic evaporates. What looks like a clever hack is actually a masterclass in accumulating technical debt.

The Local Storage Mirage

Local storage seems perfect for DIY database tools. It’s persistent, universally supported, and requires zero backend code. Just JSON.stringify() your data and slam it into localStorage.setItem(). The browser handles the rest.

Until it doesn’t.

Modern browsers typically allocate 5-10MB per origin for local storage. That’s paltry for database management. A single medium-sized table with a few hundred thousand rows can easily breach that limit. The API itself is synchronous, meaning every read or write blocks the main thread. Try importing a 50MB dump, and your UI freezes solid for seconds. The developer’s tool might handle small demo databases gracefully, but production schemas laugh at these constraints.

Worse, local storage offers zero encryption guarantees. Data sits on disk in plaintext, vulnerable to anyone with file system access. Browser profiles are surprisingly easy to exfiltrate. Compare this to modern password managers: RoboForm now supports unlocking with passkeys or hardware security keys, and even its local-only storage tier starts at $0.99/month because proper security has tangible costs. A DIY tool can’t replicate that protection model without abandoning the simplicity that made it attractive.

The Synchronization Problem Nobody Talks About

The Reddit demo glosses over a critical question: what happens when you have two browser tabs open? Or when you want to share a query with a colleague? The answer is a manual copy-paste nightmare.

Even Redis, a system literally designed for client-side caching, struggles with this. Their client-side caching architecture requires complex invalidation protocols. Using RESP3, Redis can send invalidation messages over the same connection as data queries, but many implementations still use separate connections just to manage cache coherence. The protocol-level complexity exists because keeping distributed state consistent is hard.

A DIY tool built in a weekend can’t match this. The developer inevitably faces a choice:

– Build a homegrown sync layer (abandoning the “no backend” promise)

– Accept that data diverges across sessions

– Limit the tool to strictly single-tab usage

None of these are good answers. The first option turns a simple app into a distributed systems problem. The second guarantees data loss. The third cripples usability.

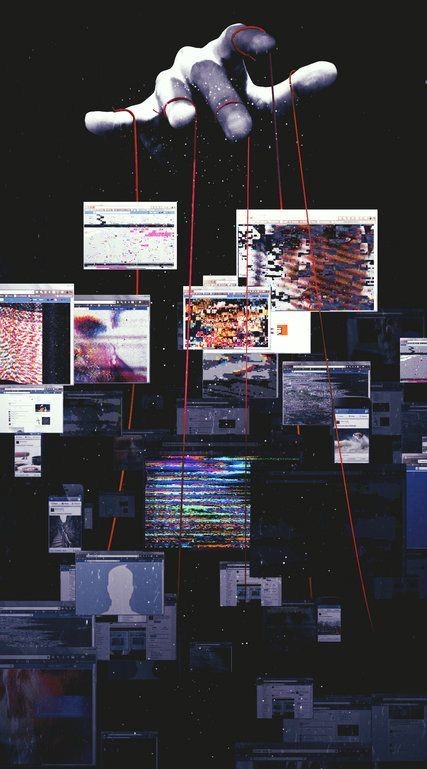

Security Architecture That’s Stuck in 2010

Database credentials are crown jewels. A standalone client-side tool must store connection strings somewhere. With local storage, that “somewhere” is a JSON file on disk, accessible to any browser extension, XSS payload, or malicious script that compromises your origin.

Modern security architecture looks very different. MEGA’s end-to-end encryption model encrypts files locally with a unique key that never leaves the device. Even MEGA’s support team can’t access user data. This isn’t just a feature, it’s a fundamental architectural choice that requires client-side cryptography, secure key management, and a threat model that assumes the server is hostile.

A browser-based database tool can’t implement similar guarantees. JavaScript cryptography in the browser is fraught with pitfalls. The same origin policy offers some protection, but XSS vulnerabilities, supply chain attacks on npm dependencies, and browser zero-days create an attack surface that traditional desktop tools don’t face.

The Scalability Ceiling You Hit Immediately

The demo showcases “smart data previews” that detect URLs and geographic coordinates. Cute, until you realize this processing happens on every page load. With no server-side cache or indexing layer, the tool must recompute everything from scratch each time you refresh.

For a table with a million rows, this isn’t just slow, it’s unusable. PostgreSQL’s query planner, index strategies, and parallel execution exist for a reason. Moving that logic to JavaScript running in a single-threaded browser environment throws away decades of database engineering.

The developer might argue it’s “just for small databases”, but that constraint is rarely respected. Users will connect it to production replicas. They will try to analyze multi-gigabyte tables. And when the tool chokes, they’ll blame the database, not the architecture.

Technical Debt That Compounds Weekly

The real pitfall isn’t the initial implementation, it’s the migration path. Every feature built on the local storage foundation makes it harder to move to a proper architecture.

Consider the evolution path:

1. Week 1: Store connection strings in local storage. Simple, works.

2. Week 4: Add query history. Still fits in 5MB.

3. Week 8: Implement saved dashboards. History grows, but it’s okay.

4. Week 12: Add collaboration features. Now you need user accounts, which requires… a backend.

At this point, you’re not just building a backend, you’re building a migration system to port all that local data to a server. Users have existing queries, dashboards, and connection configs they expect to persist. The “simple” tool has become a data portability nightmare.

This is how legacy systems are born. Not through intentional decisions, but through incremental additions to an architecture that can’t support them.

Smarter Alternatives That Don’t Sacrifice UX

You don’t have to choose between good UX and sound architecture. The local-first software movement offers better patterns.

IndexedDB + Background Sync: Store data locally using IndexedDB (which has much higher quotas and asynchronous APIs) and sync in the background using Service Workers. This maintains offline capability while enabling server-side backup and collaboration.

WASM-Powered Database Engines: Embed SQLite or DuckDB compiled to WebAssembly. The database runs client-side for responsiveness, but you can stream data from a server and persist changes back. You get real SQL engines, not JavaScript reimplementations.

Hybrid Architectures: Keep the snappy UI in the browser, but move heavy lifting to ephemeral serverless functions. A Vercel or Cloudflare Worker can run aggregations in parallel, streaming results to the client. You pay only for compute you use, and security improves dramatically because credentials stay server-side.

The Bottom Line

Building database tools that live purely in local storage feels like cheating physics, until the bill comes due. The architecture trades short-term convenience for long-term fragility: security vulnerabilities, data loss risks, scalability walls, and migration nightmares.

The Reddit demo is impressive despite its architecture, not because of it. The features are genuinely useful, but they’re built on a foundation that can’t support them. For a weekend project, that’s fine. For a tool you expect teams to rely on, it’s a liability.

Modern web architecture offers better ways to deliver that same slick UX without the pitfalls. The question isn’t whether you can build a database tool in local storage. It’s whether you should commit to maintaining the duct-tape infrastructure required to keep it from collapsing.

The answer, for any tool with ambitions beyond a single-user demo, is no.