Liquid AI just dropped LFM2.5, a family of tiny foundation models that fit in your pocket and supposedly rival models five times their size. The pitch is seductive: 1.2 billion parameters, 28 trillion tokens of pretraining, and native support for vision, audio, and multiple languages, all optimized to run on your phone, car stereo, or that Raspberry Pi gathering dust in your drawer. The benchmarks show dramatic improvements over the previous generation. The community is excited. The hype cycle is spinning.

But here’s what nobody’s saying loudly enough: these models are exactly as capable as they should be for their size, and that’s both their greatest strength and their most frustrating limitation.

The Data Ratio Wars: When More Isn’t Actually More

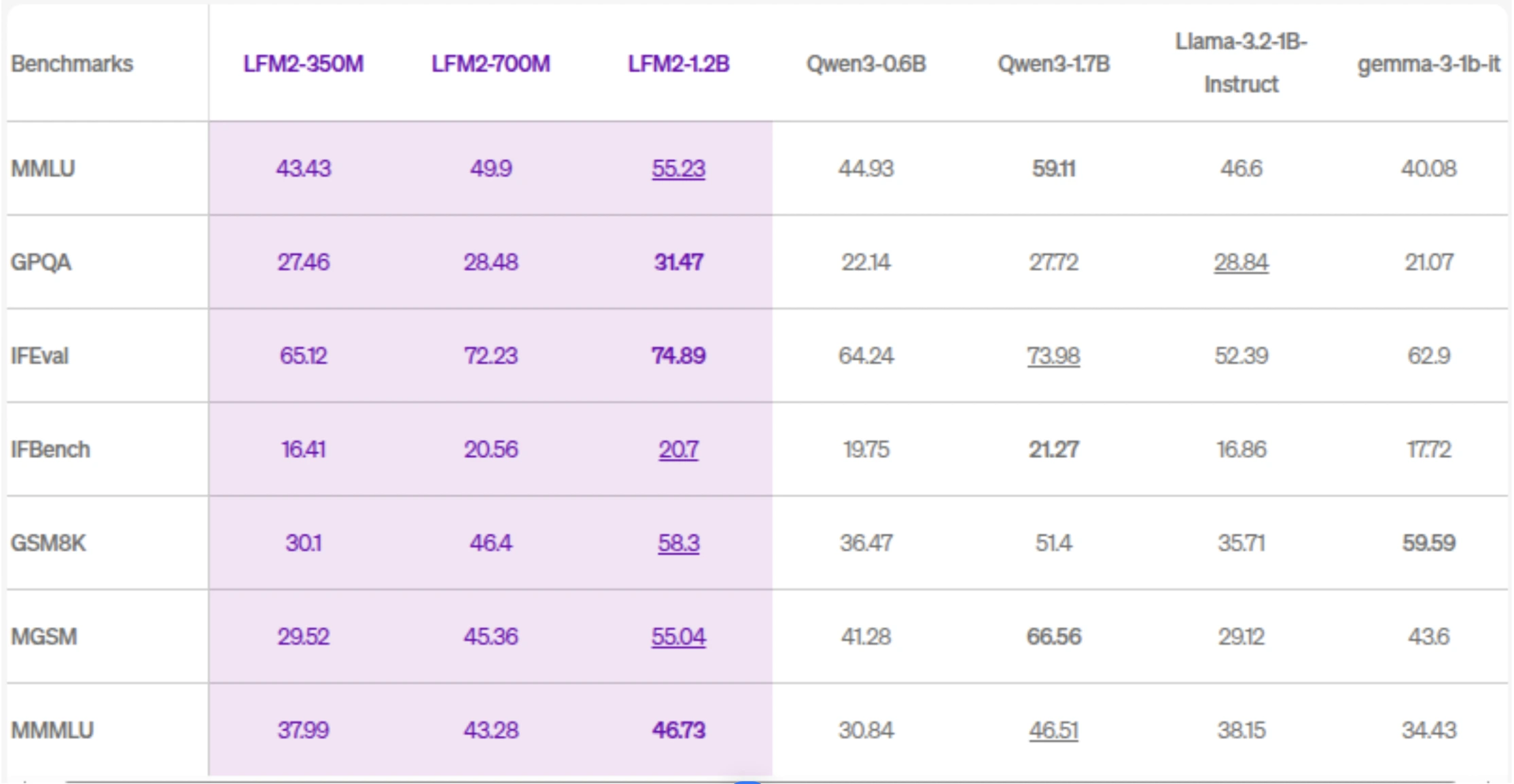

Let’s start with the number that should make you pause. LFM2.5’s training ratio sits at roughly 23,334 tokens per parameter (28T tokens ÷ 1.2B parameters). That sounds impressive until you realize it’s actually conservative compared to the competition. Qwen3-0.6B clocks in at a staggering 60,000:1 ratio, more than double LFM2.5’s data appetite per parameter.

This isn’t just academic flexing. The data-to-parameter ratio directly impacts a model’s ability to generalize and its susceptibility to memorization. Liquid AI’s approach suggests a deliberate architectural bet: train efficiently on slightly less data, but optimize the hell out of inference. The hybrid architecture, mixing multiplicative gated convolutions with sparse grouped-query attention, was discovered through hardware-in-the-loop search, not theoretical elegance. They sacrificed some theoretical capacity for real-world speed.

The result? Up to 2x faster prefill and decode on CPU compared to similarly-sized models, according to Liquid AI’s internal benchmarks. The entire training pipeline is reportedly 3x more efficient than its predecessor. But efficiency comes at a cost.

Benchmark Beauty, Real-World Beast

The benchmark numbers are genuinely striking. A community member compiled direct comparisons between LFM2 and LFM2.5:

| Benchmark | LFM2 1.2B | LFM2.5 1.2B | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFEval | 74.89 | 86.23 | +15.1% |

| IFBench | 20.7 | 47.33 | +128.6% |

| GPQA | 31.47 | 38.89 | +23.6% |

| MMLU-Pro | 25.7* | 44.35 | +72.6% |

| AIME 2025 | 3.3* | 14.00 | +324.2% |

*Scores marked with asterisks from Artificial Analysis

These gains are substantial, especially the jump in instruction-following tasks. But benchmarks are designed to be gamed, and the real story emerges when you deploy these models.

One tester reported that when asked to “Complete one sentence…”, LFM2.5 spat out five. When prompted to “Create a JSON like this…”, it produced perfect JSON structure with an extra closing brace, like a carpenter who builds a flawless cabinet but leaves a stray nail sticking out. The model feels like a 4B parameter model in speed, but instruction-fidelity remains stubbornly… small.

Vision-language capabilities show similar patterns. While it excels at image description, it fails basic OCR tasks. One user tested it on a photo containing anime characters and a Pepsi can, the model couldn’t identify either, though it described the scene’s general aesthetic. The community dubbed this the “Indiana-Waifu-Pepsi test”, a brutal real-world evaluation that benchmarks never prepare you for.

The Quantization Paradox: Why Training at FP16 Might Be a Strategic Mistake

Here’s where the discussion gets spicy. Liquid AI ships LFM2.5 in multiple formats: GGUF, ONNX, MLX at various bit depths. But the base model is trained at FP16, and this has consequences.

A developer on Reddit raised a sharp point: if the target is truly on-device deployment, why not train natively at FP8 or even FP4? Their logic is brutal and practical: a 1B model at FP16 forces users to either burn 2GB+ of RAM or quantize down aggressively, which “has heavy impact on output quality” for small models. Training a 4B model at 4-bit quantization from the start would occupy the same memory footprint without the post-quantization quality degradation.

Liquid AI’s head of post-training confirmed they’re applying RL post-training to all text models, which helps, but doesn’t solve the fundamental architectural decision. The company’s bet seems to be on flexibility, let users quantize as needed, rather than optimizing for any single deployment scenario. It’s a product decision, not a technical limitation, and it’s debatable whether it’s the right one for the “on-device” market they’re targeting.

Fine-Tuning Salvation: DPO to the Rescue

The real power of LFM2.5 might not be the base model at all, but how easily you can bend it to your will. A comprehensive tutorial on Analytics Vidhya demonstrates fine-tuning LFM2-700M using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), and the same principles apply to the 1.2B variant.

The workflow is straightforward:

1. Load the model with automatic device mapping

2. Prepare preference data (chosen vs. rejected responses)

3. Apply LoRA targeting specific modules: GLU layers, attention projections, and convolutional components

4. Train with DPO without needing a separate reward model

5. Merge and deploy a model that follows your specific formatting rules

This is where LFM2.5’s true value emerges. The base model’s instruction-following weaknesses become features, not bugs, they’re customization opportunities. One developer struggling with JSON output was advised to either fine-tune on a JSON dataset or use constrained generation frameworks like JSONFormer. The model is small enough that this isn’t computationally prohibitive, you can do it on a T4 GPU in a few hours.

The community has already begun exploring this path. A user building a narrative generation system for procedural quest creation found the raw instruct model inadequate for structured output but noted it’s “promising and may be worth learning that portion of the problem with this model as it’s small enough and fast enough to be usable.”

Use Cases: From Car Assistants to Robot Brains

The deployment scenarios being discussed reveal the model’s true niche. An enthusiast suggested installing it on an Android car head unit for offline AI assistance. Another envisioned it powering a Raspberry Pi-based robot that understands natural language and controls hardware via tool calls. The speed is undeniable, some report 250-300 tokens/second with structured output.

But there’s a catch. When another user tested LLMs for emergency scenarios, the results were alarming. In a simulated boat emergency, the model advised impossible actions (radio coast guard on a boat with no radio, drive to safety while immobilized) and dangerous ones (fire flares in a populated city). The conclusion: “pretty much every response was actively harmful or just not helpful.”

This exposes the critical gap between “agentic AI” marketing and reality. LFM2.5’s tool calling capabilities are reportedly strong for narrowly defined actions, “3D print me a whiskey tumbler” or “give driving directions”, but the model lacks world knowledge and situational awareness. It’s a pattern-matching engine, not a reasoning agent.

The Bottom Line: Right-Sized Expectations

Liquid AI’s LFM2.5 represents a meaningful advance in efficient model design. The benchmark improvements are real. The multimodal expansion is genuine. The deployment flexibility, ONNX for enterprise, MLX for Apple Silicon, GGUF for llama.cpp users, is thoughtful and comprehensive.

But this isn’t a magic bullet. It’s a specialized tool for specific jobs:

Where it shines:

– Low-latency RAG systems on edge devices

– Image description and basic vision tasks

– Multilingual chat in resource-constrained environments

– Fine-tuning substrates for domain-specific agents

– Offline-first applications with narrow, well-defined scopes

Where it struggles:

– Complex instruction following out of the box

– Structured output without additional frameworks

– OCR and precise visual understanding

– Emergency or safety-critical decision making

– General reasoning tasks requiring world knowledge

The controversy isn’t that Liquid AI oversold their model, it’s that the AI community keeps looking for one model to rule them all. LFM2.5’s sin is being exactly what it claims: a tiny, efficient foundation that requires work to deploy effectively. In an era of trillion-parameter frontier models, there’s something refreshingly honest about that.

The question isn’t whether LFM2.5 is good enough. It’s whether you’re willing to meet it where it is, fine-tune it for your needs, and accept the fundamental trade-offs of running AI on devices that fit in your palm. For many applications, that trade-off is worth it. For others, it’s a dangerous illusion of capability.

Choose wisely.

Want to experiment with LFM2.5? Start with the Hugging Face collection and check out the DPO fine-tuning guide to customize it for your specific use case. Just don’t ask it to handle your next maritime emergency.