Inside the Internet Archive’s Infrastructure: Where 20-Year-Old Code Meets a Trillion Pages

The Internet Archive operates one of the most unusual infrastructure stacks on the planet. It’s a system designed to last decades, built on hardware philosophies that would get you fired at a modern cloud company, and runs on a budget that wouldn’t cover AWS storage costs for a month. Yet it has captured over one trillion web pages and holds 99 petabytes of unique data, 212 petabytes when you count redundancy.

This is the story of what happens when you optimize for permanence instead of performance, and how a team of librarians and engineers keeps the digital past alive while fighting the present’s legal and technical battles.

The PetaBox: When “Good Enough” Beats “Best”

Walk into the Internet Archive’s San Francisco headquarters, a converted Christian Science church, and you’ll hear it before you see it: an industrial hum from hundreds of spinning disks. The sound comes from the PetaBox, a custom storage server that’s been evolving since 2004.

The PetaBox represents a fundamental rejection of enterprise storage orthodoxy. Instead of expensive RAID controllers and proprietary hardware, the Archive uses consumer-grade drives in a JBOD (Just a Bunch of Disks) configuration. Redundancy happens in software, not hardware. This approach was radical in the early 2000s when EMC and NetApp dominated with high-performance, high-cost solutions designed for millisecond latency.

| Specification | Generation 1 (2004) | Generation 4 (2010) | Current Gen (2024-2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity/rack | 100 TB | 480 TB | ~1.4 PB |

| Drive count | 40-80 drives | 240 drives | 360+ drives |

| Power/rack | 6 kW | 6-8 kW | 6-8 kW |

| Processor | Low-voltage VIA C3 | Intel Xeon E7-8870 | Modern high-efficiency x86 |

What’s remarkable isn’t just the 14x capacity increase, it’s that power consumption stayed flat. While hyperscalers battle rising electricity bills, the Archive’s thermodynamic efficiency comes from a simple trick: it uses San Francisco’s perpetual fog for cooling. No air conditioning. The waste heat warms the building in winter. This closed-loop design drops their Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) to levels that make Google’s data centers look wasteful.

The maintenance model is equally contrarian. With 28,000+ spinning disks, failures are statistical certainties, not emergencies. A single admin manages roughly one petabyte. The system uses Nagios to monitor 16,000+ checkpoints, but only alerts when failure thresholds cross a line. Drives get replaced when they’re dead, not when they’re sick. This works because the data isn’t “mission-critical” in the traditional sense, losing a single snapshot of a webpage doesn’t crash financial markets.

Crawling the Uncrawlable: Heritrix’s Identity Crisis

If the PetaBox is the Archive’s memory, Heritrix is its eyes. The Java-based crawler, born in 2003 from a partnership with Nordic national libraries, was built for a different web. It captures HTTP headers, respects robots.txt, and packages everything into WARC files, the archival equivalent of a time capsule.

But the modern web broke Heritrix. When Twitter (now X) serves a blank HTML shell that JavaScript populates dynamically, Heritrix captures the scaffolding, not the building. The result? Digital ghost towns, pages that look right in your browser but archive as empty husks.

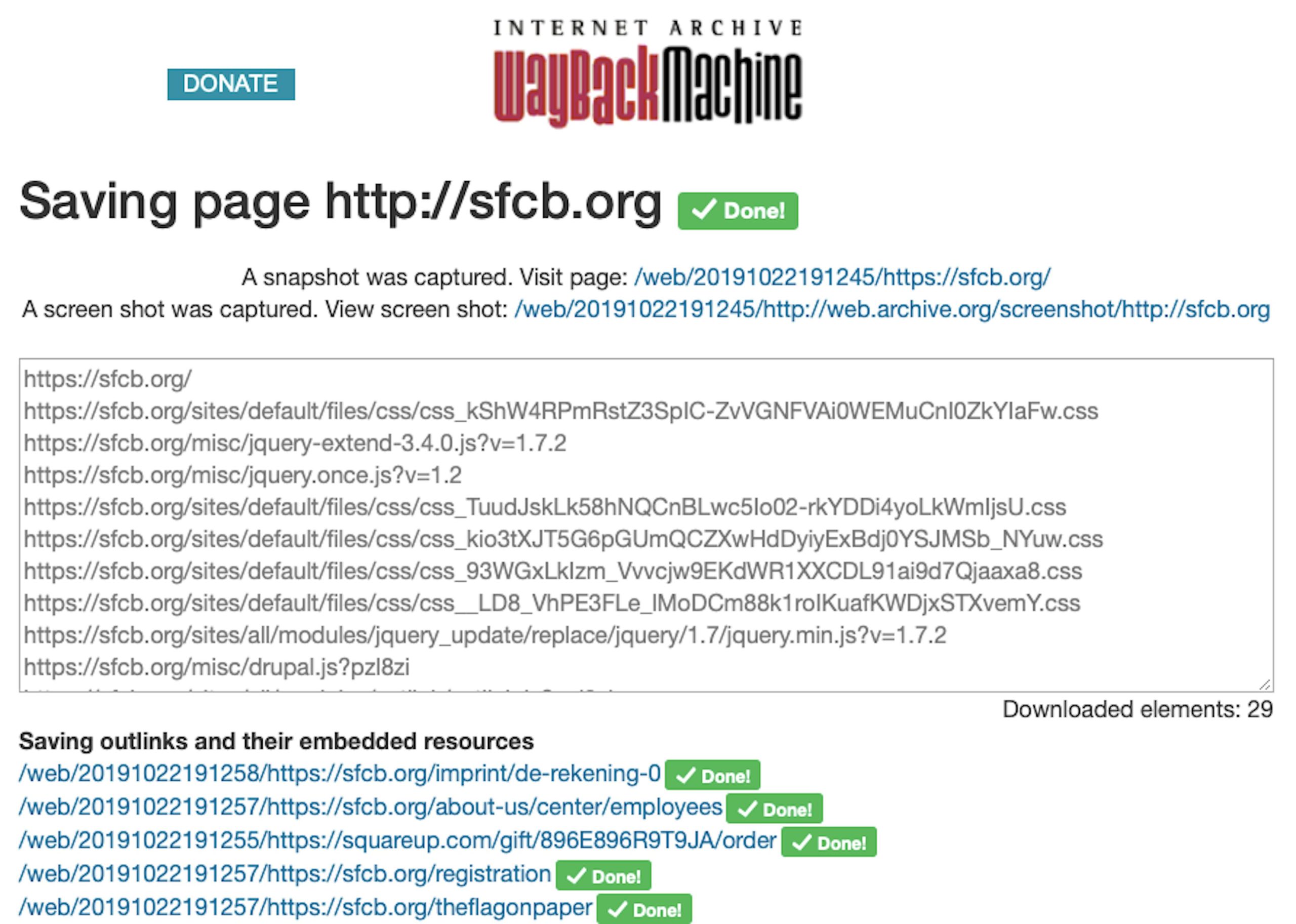

- Brozzler: A headless Chrome instance that renders pages exactly as users see them, executing JavaScript before capture

- Umbra: Browser automation that scrolls infinite feeds and triggers lazy-loading content

- Save Page Now: A user-facing feature that democratizes crawling, letting anyone archive a page on demand

This shift comes with brutal computational costs. Rendering a page in Chrome consumes orders of magnitude more CPU cycles than downloading HTML. The Archive must be selective, reserving browser-based crawling for high-value dynamic sites while using lighter tools for static content. It’s a resource allocation problem that would make any SRE wince: how do you prioritize preserving today’s ephemeral tweets against tomorrow’s potential historical significance?

The Alexa Internet partnership masked this problem for years. Until Amazon shut down Alexa in 2022, the Archive received pre-crawled data as a donation. Now it bears the full crawling burden, making the efficiency of its tooling existential.

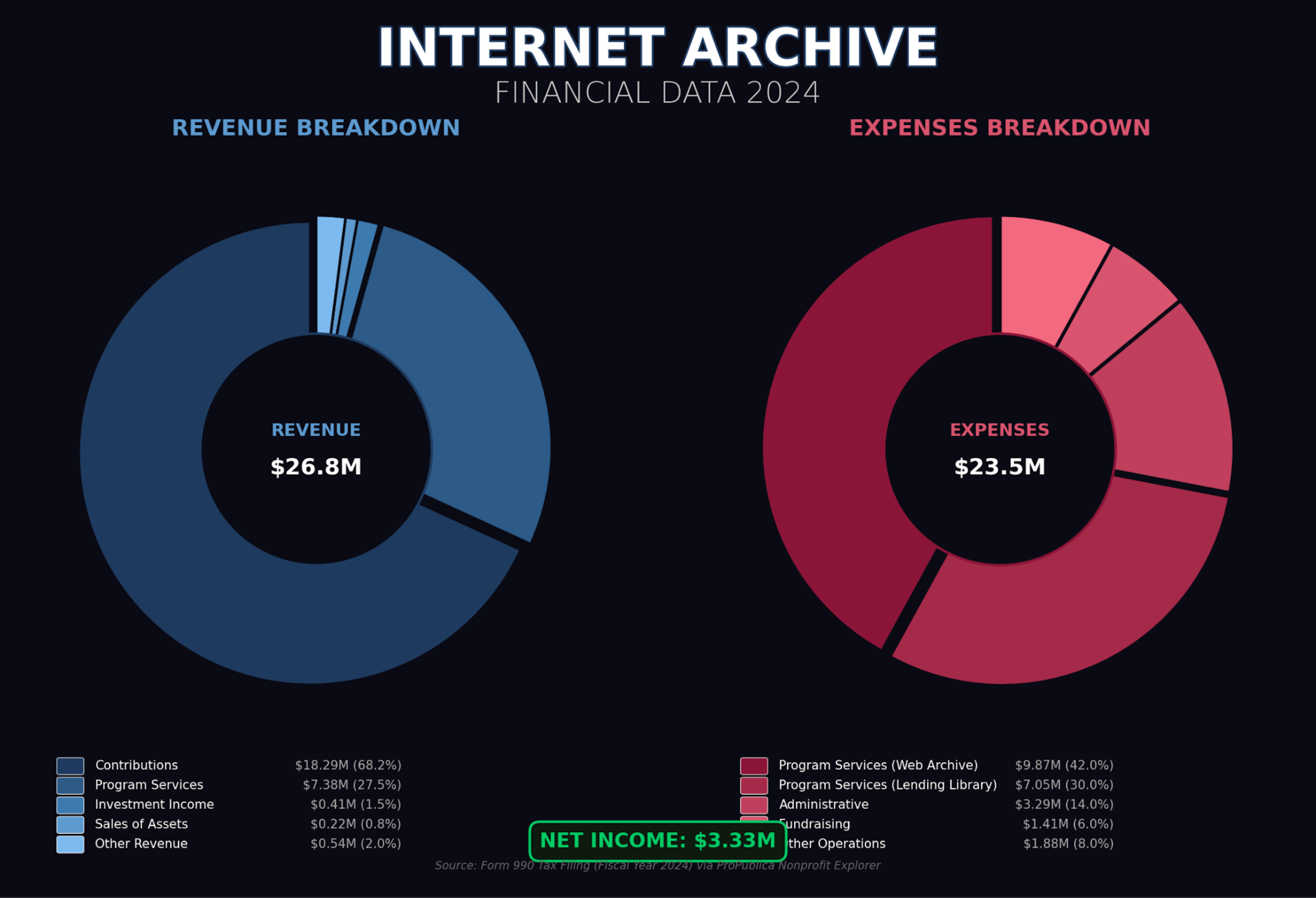

The Economics of Forever

Here’s the number that stops engineers cold: the Internet Archive’s annual budget is $25-30 million. Storing 100 petabytes on AWS would cost over $2 million per month. The Archive spends less on its entire operation than Amazon would charge for storage alone.

- 60-70% contributions and grants: Micro-donations, Mellon Foundation, Kahle/Austin Foundation, Filecoin Foundation

- Archive-It subscriptions: Libraries and universities pay $2,400-$12,000/year to curate their own web archives

- Digitization services: $0.15 per page to scan books using custom “Scribe” machines

- Vault services: $1,000 per terabyte for perpetual storage (the endowment model)

This budget covers not just hardware but a legal defense fund that’s become critical. The Hachette lawsuit over Controlled Digital Lending ended in 2024 with the Archive forced to remove 500,000 books. The Great 78 Project settlement with Sony and Universal in 2025 avoided $600 million in potential damages but restricted access to vintage recordings. These aren’t edge cases, they’re core threats to the mission.

The Decentralization Gambit

The legal assaults exposed a vulnerability: centralization. A court order or catastrophic fire at Funston Avenue could erase history. The Archive’s response is the Decentralized Web (DWeb) initiative.

By integrating IPFS and Filecoin, the Archive is fragmenting its collection into a million pieces stored across global nodes. Content gets addressed by cryptographic hash rather than location. If a government orders a server offline, the data persists elsewhere. The 2024/2025 “End of Term” crawl, capturing 500 terabytes of .gov and .mil sites before the presidential transition, is already being seeded into Filecoin for cold storage.

This is infrastructure as political resistance. It’s also a bet that decentralized protocols can solve problems that $30 million budgets cannot.

What the Hacker News Crowd Gets Wrong (and Right)

The Hacker News discussion on the Archive’s infrastructure reveals the tension between theory and practice. One commenter argued the PetaBox’s density numbers are “extremely poor compared to enterprise storage”, suggesting competitive funding for mirrors would drive costs down. Another countered that the Archive’s torrent system is broken, files get added to collections but torrents don’t regenerate, making partial downloads the norm.

The community is right about the technical debt. The Archive’s API has reliability issues. Wayback Machine downloads frequently throw 5xx errors. Rate limits cap Save Page Now at 15 URLs per minute. These aren’t design choices, they’re resource constraints made visible.

But the criticism misses the point. Enterprise storage assumes hot data, fast retrieval, and vendor support. The Archive assumes slow access, cold data, and zero vendor lock-in. When one HN user suggested tape storage for backups, Archive staff responded that tape’s latency makes it unsuitable for their access patterns. The organization knows its requirements better than outsiders theorizing about TCO.

The real controversy is generative AI. Multiple commenters noted AI companies scraping Archive content without contributing. Archive founder Brewster Kahle confirmed this, stating “Generative AI has caused some web sites to pursue dollar signs by block[ing] their sites or launch[ing] lawsuits” and that “the web seems to have turned much more adversarial.” The Archive now offers open datasets for AI researchers, trying to convert adversaries into partners.

Lessons for Engineers Building at Scale

The Internet Archive’s infrastructure teaches uncomfortable truths:

- 1. Legacy isn’t a bug, it’s a feature. Heritrix’s limitations forced innovation. The PetaBox’s JBOD design looks primitive until you realize it’s survived 20 years of tech churn.

- 2. Efficiency is contextual. A PUE of 1.1 matters more than IOPS when your budget is measured in donations. The Archive optimizes for thermodynamics, not benchmarks.

- 3. Legal architecture matters as much as technical. The Federal Depository Library designation in 2025 provided more protection than any failover system. Infrastructure includes lawyers.

- 4. Decentralization is a last resort. IPFS isn’t a performance upgrade, it’s a survival strategy for when centralization becomes untenable.

The Archive’s most impressive engineering feat isn’t technical. It’s organizational: keeping 200 petabytes online and growing while lawsuits fly and funding fluctuates. The PetaBox spins, the crawlers stumble through JavaScript frameworks, and the legal team negotiates settlements. This is what architecting for permanence looks like in an ephemeral digital world.

The machine remembers. The question is whether we’ll let it.