RBAC Is a SaaS Scalability Trap

Building a SaaS platform is a complex juggling act. You architect for performance, design for the database, and plan for deployment. Authorization often starts as an afterthought: a handful of roles scoped globally. It’s clean, simple, and utterly doomed to fail.

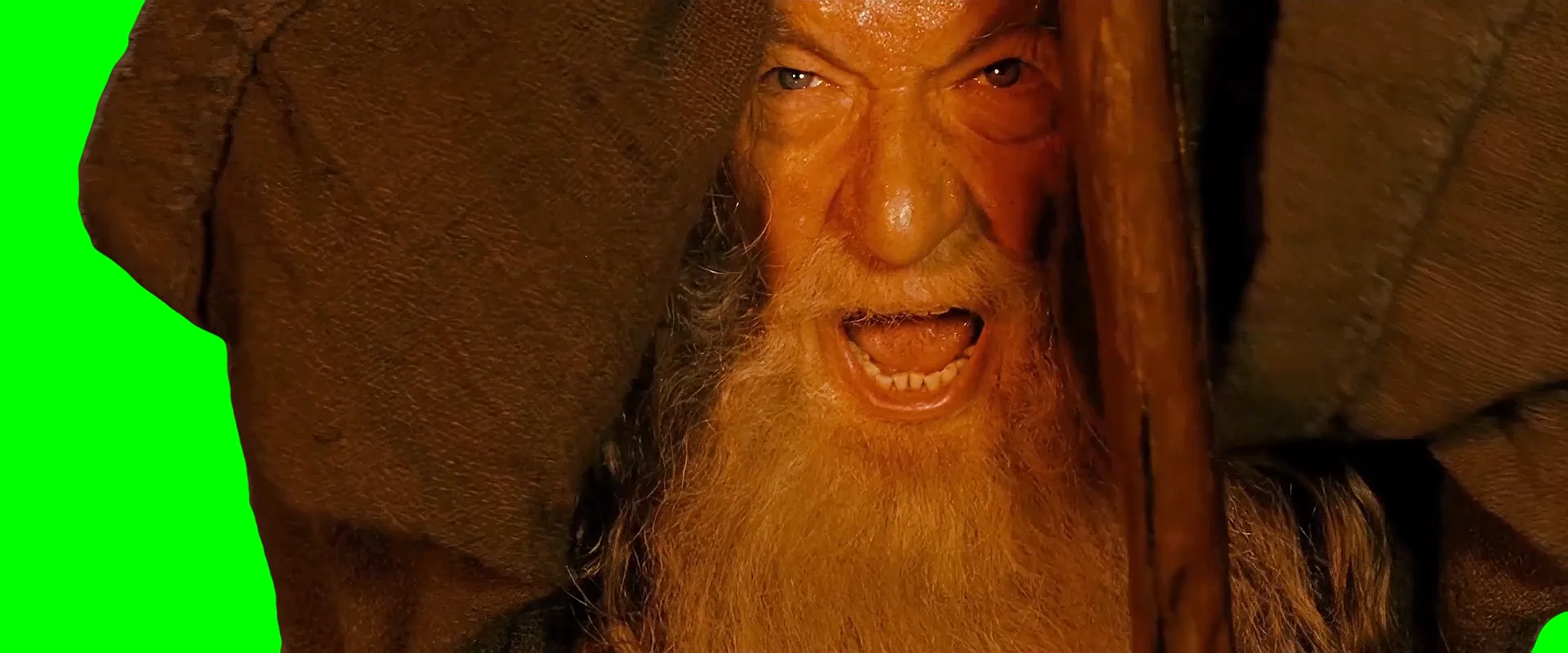

The reckoning arrives silently. Your second B2B customer signs up, and you realize Alice is an Admin for Company A but must be a Viewer for Company B. Your pristine global Admin role can’t express that. So, you create Admin_TenantA and Admin_TenantB. It feels like a hack, but the product needs to ship. Then comes the third customer, the fortieth, the thousandth. The hack becomes your reality.

Suddenly, you’re maintaining hundreds of roles. JWTs swell with claims. Permission checks are copy-pasted spaghetti across your codebase. Adding a new feature means auditing and updating dozens of role definitions. You’ve hit the role explosion.

The Anatomy of Role Explosion: Why RBAC Breaks at Scale

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) is a powerful, logical framework. It works beautifully for single-tenant enterprise software where users belong to one organization. In a multitenant SaaS world, it quickly devolves into a combinatorial nightmare.

The core failure is one of context. A SaaS application’s security model isn’t just about who you are, but where you are acting. Global roles like Editor or Viewer ignore the single most important dimension of the request: which tenant’s data is being accessed.

The workaround is where the rot sets in. You start with a clean slate of 10 base roles. But with 1,000 tenants, you find yourself managing 10 × 1,000 = 10,000 role definitions, one per tenant per role. Each new customer forces you to spin up a whole new variant set. This isn’t scaling, it’s technical debt on a geometric curve.

The architecture bakes this debt in. Look at the authorization logic in most early-stage applications:

# The anti-pattern, scattered everywhere

if user.role == "Admin" or (user.role == "Editor" and resource.owner_id == user.id):

# allow action

else:

# deny actionNow add tenant context. The checks become if user.tenant_role == "Admin_TenantA". They proliferate across every service and endpoint. Changing a rule means a full-stack hunt-and-peck refactor. Auditing "who can do what?" becomes impossible. As noted in discussions from developers, this brittle, hard-coded logic turns into a security and maintenance quagmire.

The Sprawl: More Roles Than Users

The numbers speak for themselves. If your SaaS defines 10 distinct functional roles and you grow to 1,000 tenants, a naive, tenant-locked RBAC approach necessitates managing 10,000 role definitions. These aren’t abstractions, they are discrete, enumerated entities in your identity store. You find yourself creating hyper-specific roles like "ManagerWhoApprovesUnder10kButNotOwnExpenses_TenantA", a role literally for one person in one context.

The administrative overhead is crippling. Every new feature requires you to define its permissions across every single tenant-specific role variant. The audit trail? A forensic nightmare. The risk of misconfiguration, where a user retains Editor_TenantZ privileges after leaving that organization, skyrockets. This isn’t theoretical, it’s the daily reality for teams stuck in this anti-pattern.

The Fix: Make Authorization Tenant-Aware

The solution isn’t to add more complexity, but to change the lens through which authorization is evaluated. We must move from static, global roles to context-aware, tenant-scoped permissions.

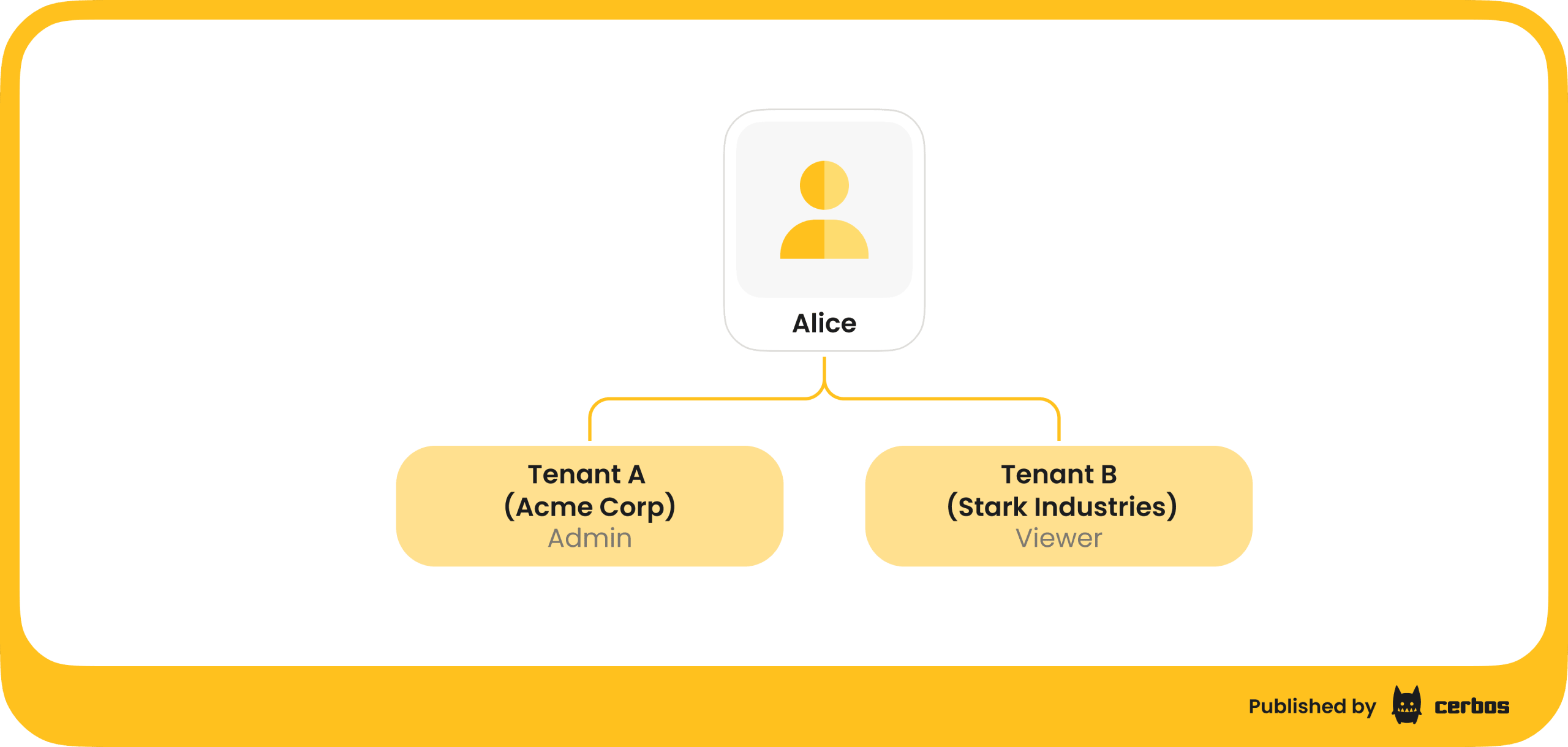

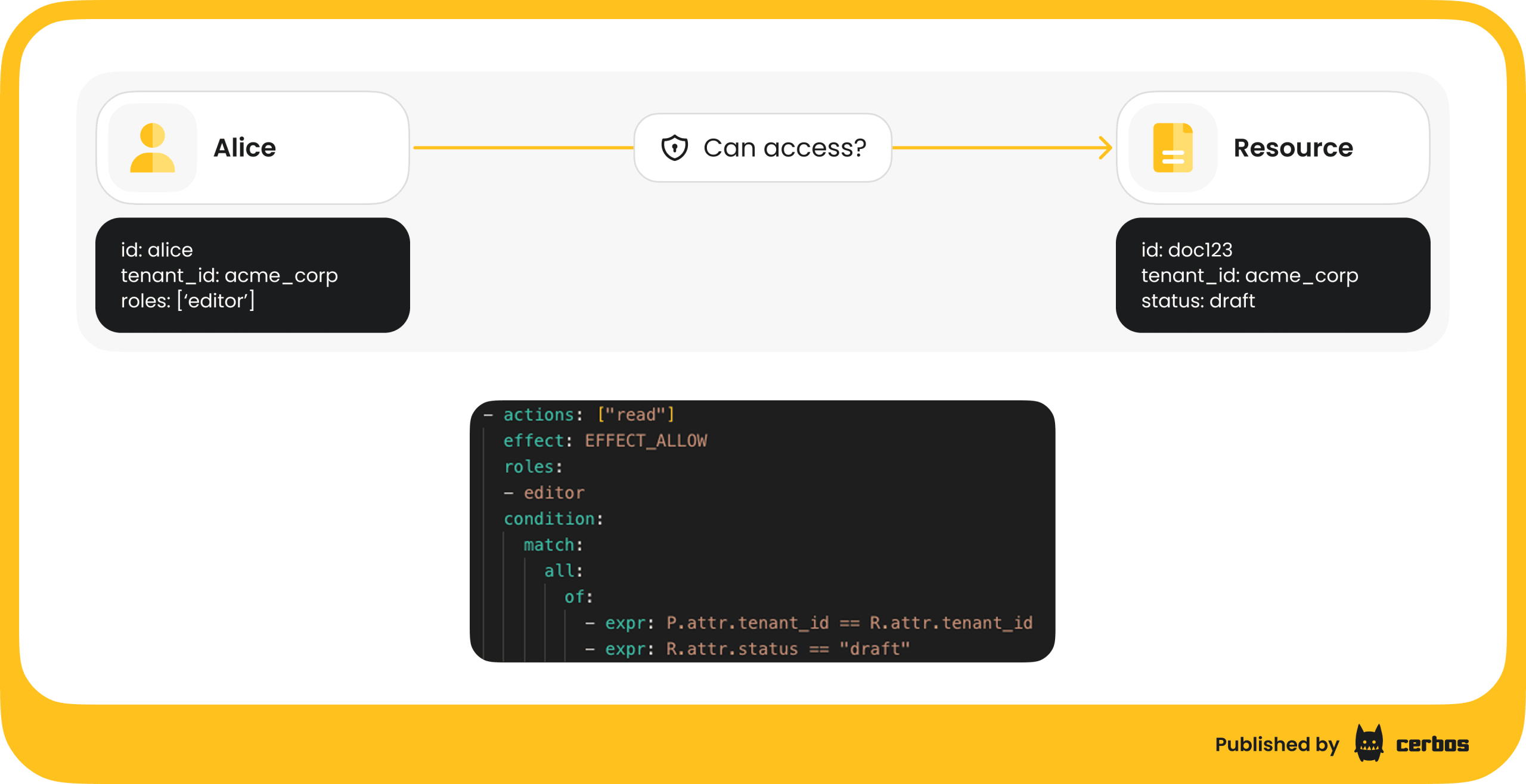

The fundamental shift is this: Instead of assigning a user a universal role like Admin, you assign them a role within a specific tenant. A user’s identity is now a tuple: (user_id, tenant_id, tenant_role). When Alice tries to edit a document, the system doesn’t ask "Is Alice an Editor?" It asks, "Is Alice an Editor in Tenant Acme for this Acme Corp document?"

Beyond Roles: Adding Granularity with ABAC

Tenant-aware RBAC fixes the multiplication problem, but roles alone are still blunt instruments. Real business logic involves nuance:

* A manager can approve expenses, but not their own.

* An editor can publish articles, but only in a "draft" state.

* A user can view reports, but only for the North America region.

This is where Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) layers on top. ABAC lets you define policies that evaluate dynamic attributes of the user (subject), the resource being accessed (object), the action, and the environment.

Consider the expense approval rule. With tenant-aware RBAC + ABAC, you write a policy like:

allow if user.tenant_role == "Manager" AND resource.owner_id != user.id AND resource.tenant_id == user.tenant_id AND resource.amount < user.approval_limit

The system checks the user’s role in the current tenant context and then layers on additional business rules. You can now enforce "separation of duties" or regional restrictions without creating ever-more-specific Frankenstein roles like RegionalManagerUnder10k.

The Architectural Imperative: Externalize Your Policy Logic

Knowing what to model (tenant-scoped roles + ABAC) is half the battle. The other half is how to implement it without scattering spaghetti code.

The critical, non-negotiable best practice is to decouple authorization logic from application code. Stop writing if/else checks in your controllers, services, and API routes. Instead, externalize it to a dedicated Policy Decision Point (PDP).

Here’s the pattern:

1. Policy Enforcement Point (PEP): Your application. When a request arrives (e.g., "Alice wants to DELETE document:123"), it gathers context: {user: Alice, action: delete, resource: document:123, tenant: Acme}.

2. Policy Decision Point (PDP): A dedicated service (like Cerbos) that holds all your authorization policies. The PEP asks the PDP: "Is this allowed?"

3. The Decision: The PDP evaluates the request against its tenant-aware and ABAC rules and returns ALLOW or DENY.

Your application code becomes gloriously simple: if (pdp.isAllowed(context)) { proceed(), } else { return 403, }. The business of why it’s allowed or denied lives entirely in the PDP’s policy files.

The benefits are transformative:

* Consistency: Every microservice, written in any language, enforces the exact same rules by querying the same PDP.

* Maintainability: To change a security rule, you update a single policy file, not a dozen code repositories.

* Testability: You can unit-test your authorization logic in isolation, independent of your application stack.

* Auditability: Every decision is logged centrally, providing a clear, immutable audit trail for compliance.

Policy as Code: Treating Security Rules Like Software

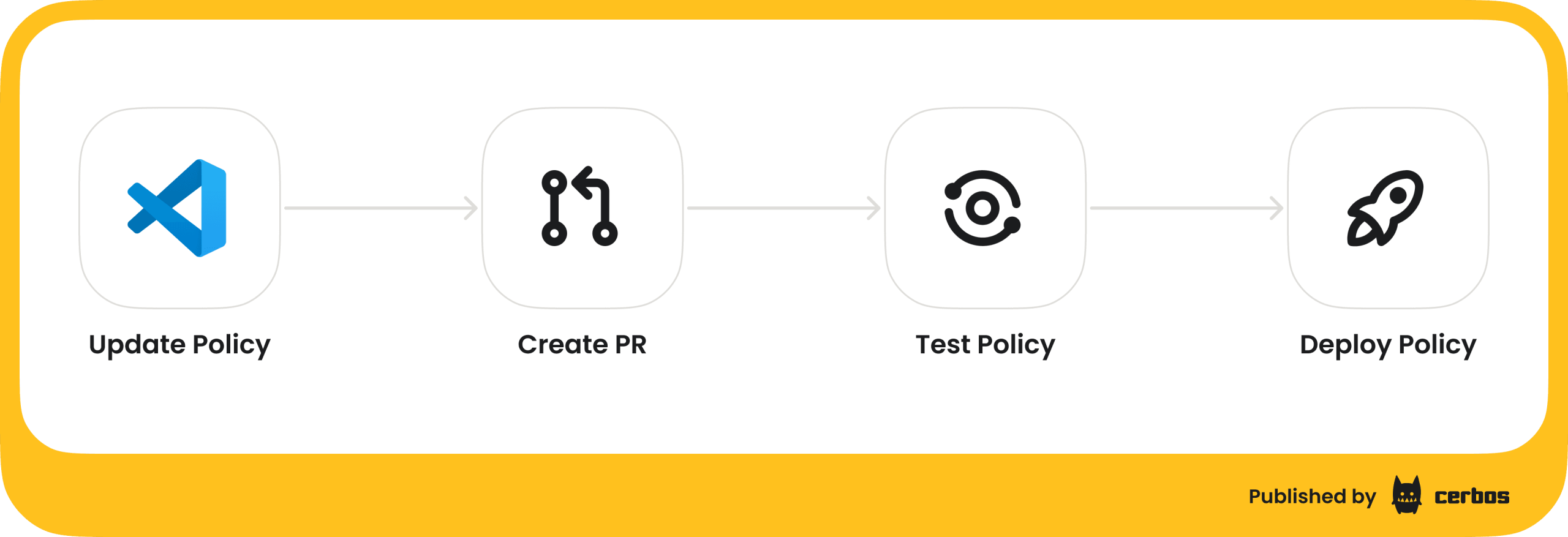

If your authorization logic is externalized, you must treat those policies with the same rigor as your application code. This is Policy as Code.

Your ABAC rules and role definitions should live in declarative files (YAML, JSON) stored in Git. Changes go through pull requests, peer reviews, and are validated by an automated CI/CD pipeline that runs a comprehensive suite of policy unit tests. Did your new rule inadvertently allow managers to approve their own expenses? The test suite catches it before it hits production.

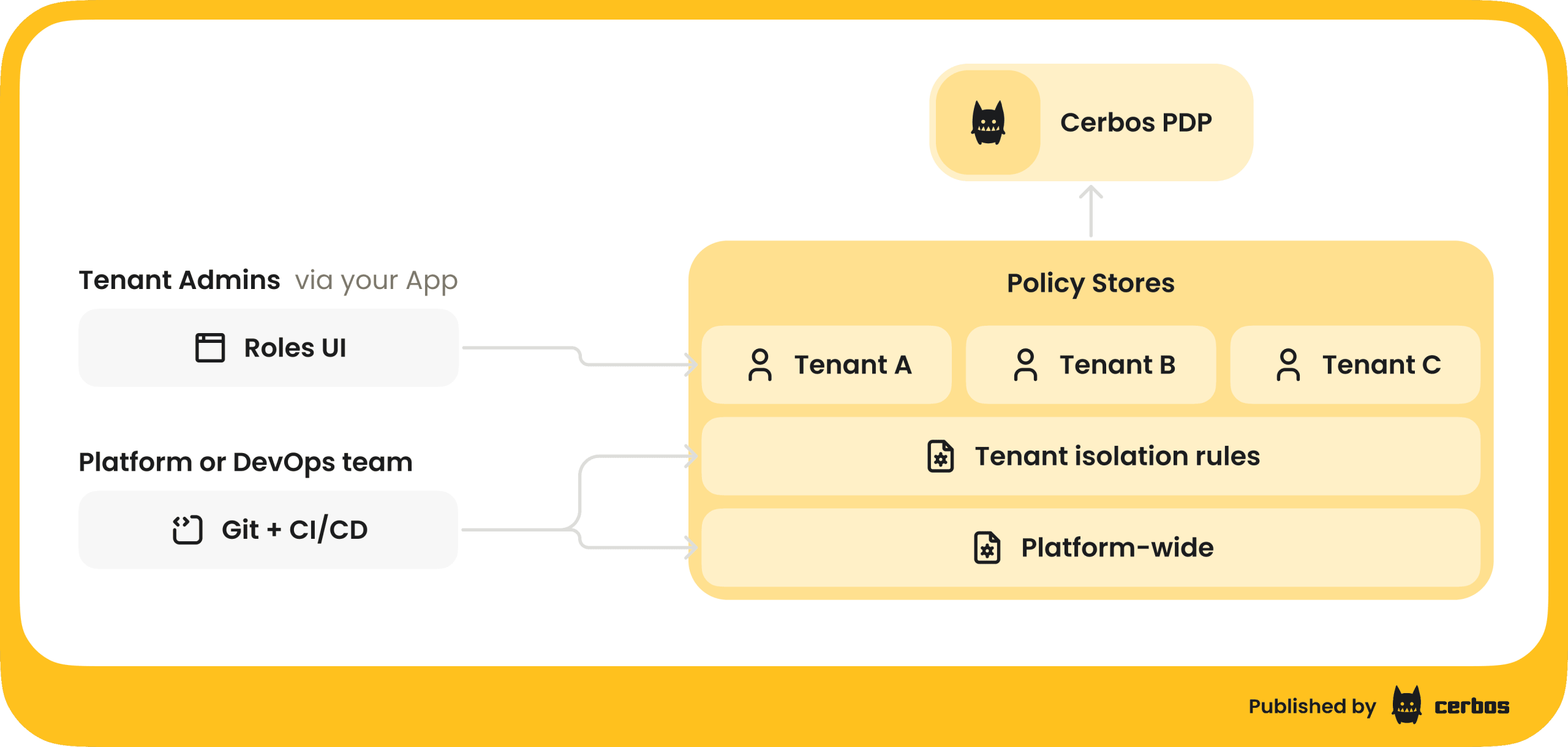

The Final Frontier: Tenant Self-Service Without Chaos

For true B2B SaaS scale, you can’t be the gatekeeper for every permission change in every customer’s organization. You need to empower tenant admins to define custom roles and fine-tune permissions, but within the safe guardrails of your platform.

This requires a layered policy architecture:

1. Platform-level policies: Immutable, Git-controlled rules that enforce absolute invariants (e.g., "A user can never access data from a tenant they don’t belong to").

2. Tenant-level policies: Dynamic rules that tenant admins can configure through your UI (e.g., creating a custom "Auditor" role that can only view North American expenses). These are pushed via API to the PDP and are scoped exclusively to that tenant.

The Scalable Authorization Blueprint

The path out of the RBAC trap is a deliberate architectural shift:

1. Abandon Global Roles. Embrace a model where roles are evaluated in the context of a tenant.

2. Augment with ABAC. Use attributes (resource status, ownership, time, location) to encode fine-grained business logic, avoiding role proliferation.

3. Externalize Decisions. Decouple authorization logic from your application by routing all "can I?" questions to a dedicated Policy Decision Point.

4. Govern Policy as Code. Manage your authorization rules with version control, testing, and CI/CD.

5. Enable Safe Delegation. Build a layered policy system that allows tenant self-service atop a rock-solid platform security foundation.

The goal isn’t just to survive the next hundred customers. It’s to build an authorization system that remains comprehensible, maintainable, and secure as you scale to ten thousand. It’s to replace the explosion of roles with the elegance of context.