The average developer spends up to 70% of their working day not writing code, but simply trying to understand it. That’s not a typo, seventy percent. According to a study by Bin Lin and Gregorio Robles on program comprehension, the act of reading, tracing, and building mental simulations of existing systems consumes the vast majority of our cognitive bandwidth. We’re not programmers anymore, we’re professional code archaeologists.

This is the cognitive rent crisis, and it’s making deep understanding a luxury few teams can afford.

The Mental Model Tax

A mental model isn’t just passive knowledge, it’s active machinery in your brain that simulates how code executes. As one programming instructor describes it, a robust mental model lets you “run code in your head”, tracing variables, predicting outputs, and debugging without constantly hitting F5. This is the foundation of expertise. It’s what separates engineers who can improvise from those who just follow recipes.

But here’s the problem: mental models don’t scale. Not really. A well-designed system might keep 1% of its complexity in your head at any given time, as one experienced architect noted in a recent discussion. The rest lives in documentation, diagrams, and tribal knowledge that decays the moment someone leaves for a startup with a better snack selection.

The cost of maintaining this internal simulation is staggering. Every new dependency, every microservice, every clever abstraction adds another layer of state to track. Modern frameworks don’t just ask for a corner of your brain, they demand a long-term lease. React’s hooks, its ecosystem, its ever-shifting patterns? That’s cognitive rent you pay monthly, with interest.

When “Boring” Becomes a Strategy

The backlash is already here. The “boring stack” movement, championed by engineers fleeing framework churn, represents a radical rejection of high cognitive rent. The philosophy is simple: bet on things that have survived multiple paradigm shifts. The terminal. HTTP. SQL. Vanilla JavaScript with no build step. These technologies are “boring” precisely because their mental models are stable, shared, and cheap to maintain.

As one developer put it, React’s mental model is “rented knowledge.” When the next thing comes along, and it will, that knowledge depreciates to zero. But the Unix philosophy has been here for 50 years. It’s not going anywhere, which means the investment in understanding it pays dividends across decades.

This isn’t nostalgia, it’s engineering economics. Simple tools fail simply. Complex tools fail in ways that require an archaeology degree to understand. When your abstraction layer breaks at 2 AM, do you understand it well enough to fix it? With a 200-line Python CLI, probably. With a framework that abstracts away the things you actually need to debug? Maybe not.

The AI Intermediary: Help or Habit?

Enter AI coding assistants. Tools like Amazon Q Developer, Google Code Wiki, and the emerging ecosystem of LLM-powered code understanding tools promise to externalize our mental models. Instead of keeping a simulation in your head, you query an AI that maintains a vector embedding of your entire codebase. Need to trace an authentication flow across 37 microservices? The AI can do it in seconds.

But this is where the controversy sharpens. Research on AI-assisted development reveals a paradox: these tools increase perceived productivity while sometimes increasing actual task completion time due to verification overhead. DeepWiki and Google Code Wiki can generate architectural documentation and answer questions about system structure, but they create a dependency. You stop building the mental model because the AI holds it for you.

The risk is subtle but severe. One study found that AI-assisted workflows can lead to “false confidence”, explanations that sound convincing but are subtly incorrect. The model might hallucinate a dependency that doesn’t exist or miss a critical cross-service interaction. When you don’t have your own mental model to validate against, you won’t even notice the error until production.

The Documentation Delusion

We’ve tried solving this with documentation. C4 models, UML diagrams, architecture decision records, these are all attempts to externalize the mental model so teams can share it. The C4 model’s four levels of abstraction (context, containers, components, code) explicitly try to serve different stakeholders with appropriate detail.

But documentation rots. A snapshot wiki generated by DeepWiki is accurate until the next commit. Google Code Wiki attempts continuous regeneration, but that just means you’re reading a real-time hallucination that might be mid-update. The fundamental problem remains: static representations of a dynamic system are always out of date.

The most successful documentation strategy isn’t comprehensive, it’s targeted. Architecture decision records (ADRs) that explain why a choice was made, not what the code does. API contracts that define boundaries. READMEs that answer “where do I start?” These work because they don’t try to replicate the mental model, they supplement it.

The Hybrid Future: Cyborg Comprehension

The most promising path forward isn’t choosing between mental models and AI, it’s combining them. Think of it as cyborg comprehension: using AI to handle the breadth while humans provide the depth.

Several emerging tools point this way. DeepWiki’s architecture-first documentation produces explicit C4 models that support reasoning about system boundaries. OpenDeepWiki exposes structured knowledge graphs that both humans and agents can query. Davia acts as an interactive workspace where AI helps generate documentation collaboratively rather than producing a static artifact.

The key is grounding. An AI explanation only becomes actionable when it’s tied to concrete code, files, symbols, line numbers. Tools with strong grounding make validation easy. Weak grounding forces you to double-check everything manually, which defeats the purpose.

For enterprise environments, this is even more critical. Amazon Q Developer’s workspace-local indexing can’t aggregate context across multiple repositories, creating architectural blindness. An engineer asking “how does JWT validation work across our auth, API gateway, and user services?” gets an incomplete answer because the tool can’t see the full system. Augment Code’s Context Engine attempts to solve this with multi-repository understanding, but it’s a commercial product in a space where open standards are still emerging.

The 70% Question

So we’re back to the 70% problem. If most of development is understanding, and our tools are making us worse at building mental models, are we optimizing for the wrong thing?

Perhaps the controversy isn’t about whether to use AI, but about what we should expect from developers. The “boring stack” crowd argues we should simplify systems until mental models are affordable again. The AI proponents argue we should surrender the mental model and trust the tool. Both are extremes.

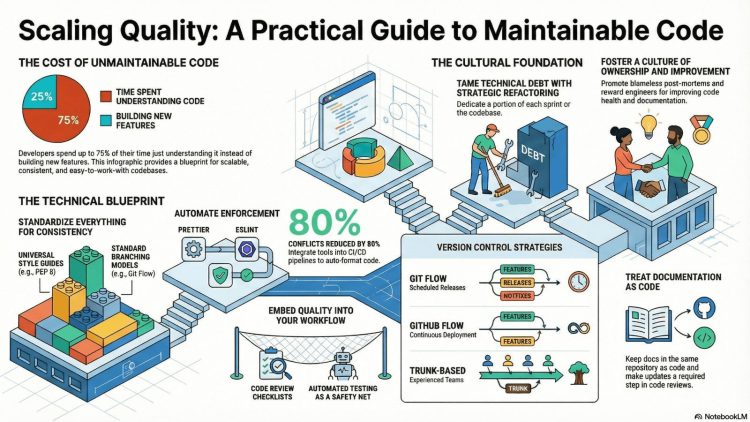

The uncomfortable truth is that we need both simpler systems and better tools. We need to reduce cognitive rent at the architectural level while augmenting human cognition at the implementation level. This means:

- Architecture-first thinking: Use C4 models and explicit boundaries to keep the big picture clear

- Selective boringness: Choose stable foundations (HTTP, SQL, vanilla JS) where you can, even if you layer complexity on top

- AI as pair programmer, not oracle: Use AI to explore, not to replace understanding. Let it find code, explain patterns, suggest changes, but always validate against your own mental model

- Living documentation: Treat docs as code, update them in the same PR, and use AI to detect when they’ve gone stale

The Luxury of Understanding

Deep understanding is becoming a luxury good. Only teams with the time, stability, and discipline can afford to maintain rich mental models of their systems. Everyone else is stuck in a loop: ship fast, lose understanding, slow down, hire more people, repeat.

The cognitive rent crisis forces a choice. You can pay upfront with architectural simplicity and disciplined documentation. Or you can pay continuously with AI subscriptions, verification overhead, and the risk of subtle errors.

But maybe there’s a third option: accept that no single human can understand modern systems, and design for collective cognition. Use AI to maintain the shared model, but keep humans in the loop for the creative, intuitive leaps that machines can’t make. Make the mental model a team asset, not an individual burden.

After all, the goal isn’t to understand every line of code. The goal is to ship working software. If AI can compress that 70% comprehension time into 20% verification time, that’s a win, even if it means your mental model is a little thinner than your predecessor’s.

The real controversy isn’t whether AI will replace mental models. It’s whether we’ll notice when the models we rely on are no longer our own.

What’s your strategy? Are you paying cognitive rent on a complex stack, going “boring” for stability, or outsourcing understanding to AI? The comments are open.